Floyd of Rosedale

*On this date, in 1934, the Floyd of Rosedale trophy story, a college game for the rights to “Floyd the Pig,” began. This football game and rivalry between the University of Iowa and the University of Minnesota began over a racial episode between the schools.

The first contended game was played at Iowa Stadium in Iowa City, Iowa, where Minnesota, on its way to the school's first-ever national championship, beat Iowa 48-12. One Iowa player took the brunt of the Minnesota attack: Ozzie Simmons. Simmons was a rarity in that era: a Black player on a major college football team.

He was a distinctive runner. He liked to grip the ball palm down, waving it hypnotically at the end of his outstretched arm like a magician's wand. He originally came to the school from Texas by hopping a freight train. Some alumni had recommended Simmons, and Coach Ossie Solem agreed to give him a tryout. He was impressive, running a kickback for a touchdown. The coach put him on the team. On the field, his breakaway runs quickly attracted media attention. Newspapers soon ranked him as one the best running backs in the nation. Writers called him the Negro halfback or nicknames like "the ebony eel." He became a symbol for young Blacks.

But most felt the crowd was unhappy with Minnesota's play against him in the 1934 game. They thought Minnesota deliberately roughed Simmons up. Some said it was because he was Black. That day, what happened in Iowa City became a long-running sore point between the two states. Simmons became the public face of the dispute. The game may have ended with the final whistle on October 1934, but some matters were far from settled. As the Gophers and the Hawkeyes left the field that day, neither side knew the game was just a scene-setter for a tumultuous confrontation the following year.

In November 1935, the Gophers boarded a Rock Island train for Iowa. A scheduling change had the team returning to play at Iowa for the second year in a row. Only about 50 Black students were enrolled. Some school officials were proud of that. They felt progressive, especially compared to southern schools, which banned blacks. This Iowa running back wasn't the only Black victim of racism; those were the days of widespread discrimination in college sports. After the game, Simmons was asked by a newspaper reporter if he thought Minnesota had played dirty. Simmons replied, "No, sir, I don't."

Fifty-plus years later, in a changed racial climate, Simmons said there was rough stuff. He told the Minneapolis Star Tribune newspaper that the Gophers hit him late and piled on after plays were over. Simmons said he always felt he was targeted because he was good. But he said the racial issue probably added some "oomph" to the hits. Minnesota displayed much discrimination against Black students in the 1930s. The men's dormitories were segregated, and the school was maintained as a white-only space.

The women's dormitories were also maintained as white-only spaces. The University of Minnesota maintained a white-only nursing program until 1929 when Frances McHie broke that color barrier. Also, dances were to be racially pure at the University of Minnesota. The University employees were also white only.

Racism was a distant argument for the all-white Gopher players as they prepared for a rematch with Iowa in November 1935. They were immersed in football, and one player was on their mind: Ozzie Simmons, one of the great players of Iowa. The Minnesota coaches were also concerned but for a different reason. Minnesota head coach Bernie Bierman received many threatening letters from Iowa fans. He received special police protection for the team when it got off the train in Iowa a couple of days before they played.

As the game drew closer, the situation deteriorated. Rumors flew. One was that fans were organizing to storm the field if Ozzie Simmons was roughed up. The day before the game, Iowa Gov. Clyde Herring seemed to funnel all the state's unhappiness into one statement. "Those Minnesotans will find ten other top-notch football players besides "Oze" Simmons against them this year; moreover, if the officials stand for any rough tactics like Minnesota used last year, I'm sure the crowd won't." The news quickly reached Minnesota. Coach Bierman threatened to break off athletic relations.

At this point, Minnesota Gov. Floyd B. Olson knew he had to lighten the mood. He sent the following telegram to Iowa Gov. Herring on game-day morning. "Dear Clyde, Minnesota folks are excited over your statement about the Iowa crowd lynching the Minnesota football team. If you seriously think Iowa has any chance to win, I will bet you a Minnesota prize hog against an Iowa prize hog that Minnesota wins today."

The Iowa governor accepted, and what became known as the Floyd of Rosedale Prize was born. Herring followed Olson's cue. He joked that finding a prize hog in Minnesota would be hard since they all were "scrawny." Word of the bet reached Iowa City as the crowd gathered at the stadium. Things calmed down, and the game was calm football; Minnesota won 13-7. Simmons himself praised both teams for their clean play.

Iowa Gov. Herring brought a live pig to the Minnesota Capitol building in St. Paul and took it inside to Gov. Olson. The hog was dubbed "Floyd" after the Minnesota governor, "Rosedale" for the animal's Iowa birthplace. Floyd of Rosedale started as a game trophy but became a normal farm animal in southeast Minnesota. Within weeks of winning the pig, Gov. Olson gave him away in an essay contest titled "Opportunities for life on the farm."

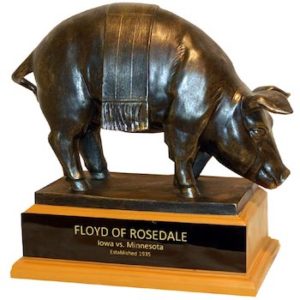

The winner gave Floyd to the University of Minnesota. The school sold Floyd to the Donald Gjerdrum family farm for $50. Floyd, the pig, died of cholera in July 1936 and was buried near the trees on the farm six miles from Iowa, almost halfway between the two schools. A bronze statue replaced the animal as the football's annual prize.

The real Floyd, Gov. Olson, died less than a month later from cancer. Simmons said he never took much interest in the Floyd of Rosedale trophy because of the racial era it recalled. Simmons did not play pro football because the NFL banned black players then. He played some minor league ball, joined the Navy, and became a Chicago public school teacher and a stockbroker.

The Floyd of Rosedale trophy is about football, a celebrated college rivalry, and America's racial history. It began in an era when racial discrimination was more widespread and protected at the highest levels of government. All Simmons wanted was a chance. The trophy is an ever-present reminder of how precious that right is.