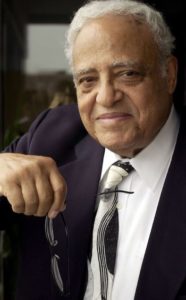

Benjamin Hooks

*Benjamin Hooks, a Black activist, lawyer, and minister, was born on this date in 1925.

Benjamin Lawson Hooks was born in Memphis, Tennessee, the fifth of seven children of Robert B. Hooks and Bessie White Hooks. His father was a photographer and owned a photography studio with his brother Henry, known at the time as Hooks Brothers. Still, he recalls that he had to wear hand-me-down clothes and that his mother had to be careful to stretch the dollars to feed and care for the family. His paternal grandmother, Julia Britton Hooks, graduated from Berea College in Kentucky in 1874, the second American black woman to graduate. She played piano publicly at age five and 18 and joined Berea’s faculty, teaching instrumental music. Her sister, Dr. Mary E. Britton, also attended Berea and became a physician in Lexington, Kentucky.

In his youth, he had felt called to the Christian ministry. Hooks enrolled in LeMoyne-Owen College in Memphis, graduating in 1944 from Howard University. From there, he joined the Army and guarded Italian prisoners of war. He found it humiliating that the prisoners were allowed to eat in restaurants where he was barred. He left the Army with the rank of staff sergeant. After the war, he enrolled at the DePaul University College of Law. He graduated from DePaul in 1948 with his J.D. (law) degree. Upon graduation, Hooks immediately returned to his native Memphis.

By 1949, Hooks had earned a local reputation as one of the few black lawyers in Memphis. At the Shelby County Fair, he met a 24-year-old science teacher named Frances Dancy. They began to date and were married in Memphis in 1952. In 1954, only days before the U.S. Supreme Court handed down Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, he appeared on the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL) sponsored roundtable, Thurgood Marshall and other black Southern attorneys to formulate possible litigation strategies.

Hooks was ordained as a Baptist minister in 1956 and began to preach regularly at the Greater Middle Baptist Church in Memphis while continuing his law practice. He joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (then known as the Southern Negro Leaders Conference on Transportation and Nonviolent Integration) along with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

He also pioneered restaurant sit-ins and other boycotts of consumer items and services. Hooks ran unsuccessfully for the state legislature in 1954 and for juvenile court judge in 1959 and 1963. In 1965, Tennessee Governor Frank G. Clement appointed him to fill a vacancy in the Shelby County criminal court, the first black criminal court judge in Tennessee history. His temporary appointment to the bench expired in 1966, but he campaigned for and won election to a full term in the same judicial office.

By the late 1960s, he flew to Detroit twice a month to preach at the Greater New Mount Moriah Baptist Church. He also continued to work with the NAACP in civil rights protests and marches. His wife Frances became his assistant, secretary, advisor, and traveling companion, even though it meant sacrificing her career. Hooks produced local television shows in Memphis while strongly supporting Republican political candidates.

In 1972, President Richard Nixon appointed Hooks as one of the five commissioners of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The Senate confirmed the nomination, and as a member of the FCC, Hooks addressed the lack of minority ownership of television and radio stations, the minority employment statistics for the broadcasting industry, and the image of blacks in the mass media. Hooks completed his five-year term on the board of commissioners in 1978, but he continued to work for black involvement in the entertainment industry.

On November 6, 1976, the 64-member NAACP board of directors elected Hooks as executive director. In the late 1970s, the membership had declined from a high of about 500,000 to only about 200,000. Hooks was determined to increase enrollment and raise money for the organization's severely depleted treasury without changing the NAACP’s goals or mandates. In his early years at the NAACP, Hooks had bitter arguments with Margaret Bush Wilson, chairwoman of the NAACP’s board of directors.

In 1980, Hooks explained why the NAACP was against using violence to obtain civil rights: “There are a lot of ways an oppressed people can rise. One way to rise is to study, to be smarter than your oppressor. The concept of rising against oppression through physical contact is stupid and self-defeating. It exalts brawn over brain. And the most enduring contributions made to civilization have not been made by brawn; they have been made by brain.”

Early in 1990, Hooks and his family were the targets of a wave of bombings against civil rights leaders. Hooks was also a staunch advocate of self-help among the black community, urging wealthy and middle-class blacks to give time and resources to those less fortunate. “It’s time today... to bring it out of the closet: No longer can we proffer polite, explicable reasons why Black America cannot do more for itself,” he told the 1990 NAACP convention delegates. “I’m calling for a moratorium on excuses. I challenge all of us in black America today to set aside our alibis.”

By 1991, some younger NAACP members thought Hooks had lost touch with black America and ought to resign. Hooks and his wife handled the NAACP’s business and helped plan its future for over 15 years. In February 1992, at age 67, he announced his resignation from the post, calling it “a killing job,” according to the Detroit Free Press.

He served as a distinguished adjunct professor for the Political Science department of the University of Memphis. 1996 the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change was established at the University of Memphis. The Institute works to advance understanding of the legacy of the American Civil Rights Movement and other movements for social justice – through teaching, research, and community programs that emphasize social movements, race relations, strong communities, public education, effective public participation, and social and economic justice.

Hooks’ professional memberships included the American Bar Association, the National Bar Association, the Tennessee Bar Association, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Tennessee Council on Human Relations. In 1986, Hooks was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In 1988, Hooks received an honorary doctorate from Central Connecticut State University. Another award for Hooks was the Benjamin L. Hooks Distinguished Service Award, awarded to persons for efforts in implementing policies and programs that promote equal opportunity through the NAACP.

In 2007, Hooks received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush. In 2008, he was inducted into the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame at the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site. Also, the Memphis Library's main Branch is named in his honor. Benjamin Hooks died on April 15, 2010, in Memphis.