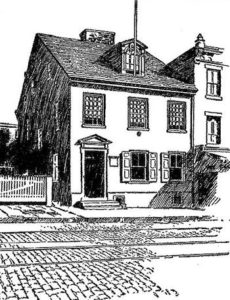

Thones Kunders house

*On this date, in 1688, the Registry shares an article on Abolitionists and the formal beginning of organized group Abolitionism in America.

This movement sought to end slavery in the United States and was active both before and during the American Civil War. In the Americas and Western Europe, abolitionism was a movement that sought to end the Middle Passage (Atlantic slave trade) and free slaves.

Enlightened white-English Quaker thinkers in America condemned slavery on humanistic grounds. They and some Evangelical denominations condemned slavery as un-Christian. At that time, most slaves were Africans or descendants of Africans, but thousands of Native Americans were also enslaved. In the 18th century alone, as many as six million Africans were transported to the Americas as slaves, at least a third on British ships to North America. The first statement against slavery in America was written in 1688 by the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers).

On February 18, 1688, Francis Daniel Pastorius of Germantown, Pennsylvania, drafted the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery, a two-page condemnation of the practice, and sent it to the governing bodies of their Quaker church. The document intended to stop slavery within the Quaker community, where 70% of Quakers owned slaves between 1681 and 1705. It acknowledged the universal rights of all people. While the Quaker establishment did not take action at that time, the unusually early, clear, and forceful argument in the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery initiated the spirit that finally led to the end of slavery in the Society of Friends (1776) and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1780).

The Quaker Quarterly Meeting of Chester, Pennsylvania, first protested in 1711. Within a few decades, the slave trade was under attack, opposed by Quaker leaders such as William Burling, Benjamin Lay, Ralph Sandiford, William Sotheby, and John Woolman. This formal movement was empathetic and intersected with the many Black slaves, revolutionaries, white allies, and groups throughout the Antebellum era of America. Many included Denmark Vesey, Harriet Tubman, Nate Turner, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Robert Purvis, William Wilberforce, and John Brown.

Slavery was banned in the colony of Georgia soon after its founding in 1733. The colony's founder, James Edward Oglethorpe, fended off repeated attempts by South Carolina merchants and land speculators to introduce slavery to the colony. In 1739, he wrote to the Georgia Trustees urging them to hold firm: If we allow slaves, we act against the very principles we associated with, which was to relieve the distress. Whereas, now we should occasion the misery of thousands in Africa by setting men upon using arts to buy and bring into perpetual slavery the poor people who now live there free— James Edward Oglethorpe, 1739. The struggle between Georgia and South Carolina led to the first debates in Parliament over the issue of slavery, occurring between 1740 and 1742. Within the British Empire, the Massachusetts courts began to follow England when, in 1772, they denied slave owners in England the legal right to move an enslaved person out of England without the person's consent.

The decision, Somerset v. Stewart, did not apply to the colonies. Between 1764 and 1774, seventeen slaves appeared in Massachusetts courts to sue their owners for freedom. Boston lawyer Benjamin Kent represented them. In 1766, Kent won a case (Slew v. Whipple) to liberate Jenny Slew, a mixed-race woman kidnapped in Massachusetts and then handled as a slave. According to historian Steven Pincus, many colonial legislatures worked to enact laws limiting slavery. The Provincial legislature of Massachusetts Bay, as noted by historian Gary B. Nash, approved a law "prohibiting the importation and purchase of slaves by any Massachusetts citizen." The Loyalist British Governor Thomas Hutchinson vetoed it, which was poorly taken by the population.

The intersectionality of the American abolitionist movement and similar movements in Africa, South America, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America created an inevitable force for human freedom in the Western Hemisphere. This includes men like Ottobah Cugoano, Vicente Guerrero, Yanga, Toussaint Louverture, Zumbi, Benkos Bioho, and more.

Between 1780 and 1804, all Northern states, beginning with An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery from Pennsylvania in 1780, passed legislation abolishing slavery, although that did not mean "freeing the slaves." In general, it meant only that the commerce in slaves, the slave trade, was abolished or driven underground. As for emancipation, Massachusetts ratified a constitution that declared all men equal; freedom suits challenging slavery based on that principle brought an end to slavery in the state. In New York, slaves became indentured servants who became free in 1827. Sometimes, the only change was that children of slaves were born free. In Virginia, the courts interpreted similar declarations of rights as not applicable to Black Africans or African Americans. All the states banned the international slave trade by 1790. South Carolina did so in 1787, but in 1803, it reversed itself. Publications that supported the abolitionist movements also played a key role in its success. Some included the Freedoms Journal, Genius of Universal Emancipation, and the Liberator Newspaper. And the North Star Newspaper.

Human rights were always a point of reference for abolition. William H. Johnson, a former enslaved jockey who used his prize winnings to buy his freedom, wrote: “If the anti-slavery cause had been productive of no other good,” he would write in a letter published in November 1841, “it has led to the inquiry of the nature of all those various relations of human beings, commonly known by the name of human rights.”Now was the time, he believed, to make human rights “a great central, practical truth, and not a mere rhetorical flourish.”

During the ensuing decades, the abolitionist movement grew in Northern states, and Congress regulated the expansion of slavery as new states were admitted to the Union. The United States federal government criminalized the international slave trade in 1808, prohibited it in the District of Columbia in 1850, and made slavery unconstitutional altogether in 1865 (see Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution). This directly resulted from the Union (Northern) victory in the American Civil War. The central issue of the war was slavery. American abolitionism was not a movement of the virtuous North directed against the sinful South. Slavery in the North was dying but not dead. Free Blacks, seen as immigrants who would work for cheap, were just as unwelcome in the North as in the South, if not more so, and subject to discrimination and mistreatment almost inconceivable in the 21st Century.

It was not only legal but routine to discriminate against and mistreat Blacks. Anti-free Black riots were common in the North, not the South. In its early years, the abolitionist movement was directed at Northerners, convincing them, by providing speakers and documentation, that slaves, frequently if not always, were mistreated in the South. Incidentally, Northerners saw firsthand that Blacks, some of whom were eloquent, well-educated, and good Christians, were not inferior human beings. Northern support for ending slavery once a radical position grew steadily. Historian James M. McPherson defines an abolitionist "as who before the Civil War had agitated for the immediate, unconditional and total abolition of slavery in the United States." He does not include antislavery activists such as Abraham Lincoln, the U.S. president during the Civil War, or the Republican Party, which called for the gradual ending of slavery.

Abolitionism in the United States was an expression of moralism and usually had a religious component: slavery was incompatible with Christianity, according to many religious abolitionists. It often operated with another social reform effort, the temperance movement. Slavery was also attacked, to a lesser degree, as harmful on economic grounds. Evidence was that the South, with many enslaved workers, was poorer than the North, with few.

After emancipation and the civil and voting rights laws that followed, this movement evolved into activism to maintain human progress through these laws. This article does not forget the countless people not mentioned who lost their lives or endured hardship as abolitionists to end slavery. The same is true from reconstruction to the present for those involved in activism to make democracy work for all citizens.

Image: Thones Kunders's house at 5109 Germantown Avenue, where the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery was written. From Jenkins (1915).