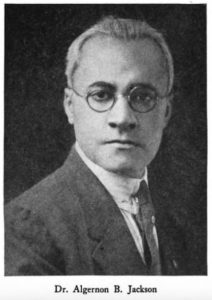

Algernon Jackson

*Algernon Jackson was born on this date in 1878. He was a Black physician, surgeon, author, and columnist.

Algernon Brashear Jackson was born in Princeton, Indiana, to Charles A. Jackson and Sarah L. Brashear Jackson. His mother was a public school teacher in the area and received an extensive education at several institutions, including Indiana University, the University of Pennsylvania, Temple University, and Drexel Institute. Jackson considered himself mulatto and belonged to the Republican party.

He attended Indiana University for his undergraduate education and then continued to Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, where, in 1901, he earned his M.D. He completed additional post-graduate work at Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania. He became an assistant surgeon at Philadelphia Polyclinic Hospital, an institution run exclusively by white physicians. He was the first and only Black surgeon to work at the hospital then and kept the position for thirteen years. Jackson lived in privileged circles within the Black community and had clear ties to Booker T. Washington and Henry McKee Minton, among others. In 1904, Jackson, Minton, and two other fellow African American medical professionals became the founding members of Sigma Pi Phi, the first Black Greek Letter organization, to unite other like-minded black professionals in the North.

In 1907, Jackson co-founded the Mercy Hospital School for Nurses and undertook the position of Surgeon-in-Chief, which he maintained for 15 years before becoming the hospital's Superintendent. He married Elizabeth A. Newman in Media, Pennsylvania, on June 20, 1920. In 1921, He accepted a job at Howard University. He was succeeded as Superintendent by Minton. From 1921 to 1934, he was a professor of bacteriology and public health; from 1921 to 1925, he was the director of the School of Public Health; and from 1926 to 1928, he was a physician in charge at Howard University.

In 1911, he made headlines in the medical community for discovering magnesium sulfate injection as an effective treatment for rheumatism. He authored three books: Evolution and Life: A Series of Lay Sermons, The Man Next Door, and Jim and Mr. Eddy: A Dixie Motorlogue. Jackson was extremely concerned with the relatively high mortality rates of African Americans, specifically those in the poverty-stricken South. He believed educating the African American community on public health and hygiene was the most effective way to uplift the race in all aspects of life.

Although primarily based out of Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., Jackson made several tours through the South, speaking at Black public schools and community youth centers on hygiene and disease prevention and visiting hospitals to determine the state of Negro health care throughout the country. His findings from the latter tours were published in several journals. They included calls to action for the government and the public to improve clinical facilities for Southern Blacks by allocating more money, better equipment, more qualified staff, and, most importantly, preventative educational components.

Jackson also used his platform as a public health columnist in several African American regional newspapers to report on his findings of the state of Negro health in America, which were overwhelmingly described as disappointing or atrocious. The audience he reached through his journalistic work in publications like the Pittsburgh Courier, the New York Amsterdam News, the Baltimore Afro-American, and the Chicago Defender was overwhelmingly middle-class, Northern Blacks. His regular columns ranged from health advice (“Afro Health Talk” in the Baltimore Afro-American) to opinion pages (“Weekende Mosaics” in the Pittsburgh Courier). Still, all were ultimately concerned with the social stature of Blacks.

In his article “The Need for Health Education Among Negroes,” he underscored the notion that “no man, whatever his motive may be, can help lift his brother without lifting himself.” In other words, educating the African American community in public health and hygiene would not only lift the race by reducing mortality and illness rates but also benefit the whites who would inevitably find themselves in contact with Blacks. However, it was abundantly clear that, in Jackson's eyes, not all African Americans shared equal responsibility for the subpar health of the race. Most often, the blame for the harmful ignorance of public health issues fell on the shoulders of the poor Southern blacks. In turn, Jackson asserted that it was up to black medical leaders to “save great people who know little about how to save themselves.” Most of Jackson's writing for the lay public and medical community included implications of classism and elitism that set Southern Blacks lower on the hierarchy than wealthier Blacks in cosmopolitan northern cities.

On at least one occasion in “Weekend Mosaics,” Jackson assured his broadly educated Northern readership that their illness and death rates were no worse off than those of Northern whites and that they were thusly not to blame for high Negro mortality. Southern blacks, on the other hand, he claimed, “have no appreciation of [life] and use it to no more purpose than does the dumb animal.” As such, he called upon the educated black masses, much like he did with the black medical community, to reach the “poor unfortunate neglected members of our race” and teach them “that better living means better health, longer life, a finer happiness, and a greater power for doing the things which we all as a race want to do…[to] make us unafraid and unconquerable.”

In 1928, he reported for the Philadelphia Tribune on a German study in which the blood of Jews, Ukrainians, and Russians was tested and analyzed for differences. Jackson wrote that variations were observed (like how quickly the blood reacted with different chemicals, which they chalked up to “oxidation”). Still, the implications and significance of these findings were left simply at the fact that people of different “races” or ethnicities are, in fact, “chemically different.” Regardless of the vagueness of the study and its probable ties to Nazi-backed eugenic exploration, Jackson took a great interest in the experiment and suggested that “racial identity may be fixed by chemical analysis” in the future. He additionally implied that determining racial makeup through objective measures could prove “more unpopular with whites than with Negroes,” either because it will reveal less pure bloodlines in whites or chemical superiority in Blacks.

Despite his occasional favoritism of Northern Blacks and apparent eugenic interests, Jackson did not spare even the most refined and economically advantaged Blacks personal hygiene advice, particularly in his “Afro Health Talk” column. Although he was touted in this publication as a “Health Authority and Stomach Specialist,” his column explored all matters of preventative medicine and often linked health issues with the societal perceptions or stereotypes of Blacks. For example, in a column about tuberculosis prevention, Jackson blamed “ignorance, carelessness, indifference, immorality, vicious living, and unwillingness to accept advice” for the “untutored” Black community's mortality rates from tuberculosis. But even more so, it was the fault of “the social and economic maladjustment born of a slimy race prejudice indigenous to America” that prevented “all citizens, black and white, [from facing] life and death on equal terms.” Algernon Jackson died on October 22, 1942, in his home in Washington, D.C., at age 64.