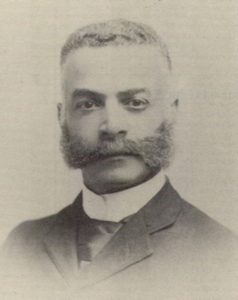

Archibald Grimke

*Archibald Grimké was born on this date in 1849. He was a Black lawyer, intellectual, journalist, and activist.

Archibald Henry Grimké was born into slavery near Charleston, South Carolina, in 1849. He was the eldest of three sons of Nancy Weston, who was also born into slavery, daughter of an enslaved black African woman and her white owner, Henry W. Grimké, (then) a widower. After becoming a widower, his father moved with Weston to his plantation outside of Charleston. He was a father to his sons, teaching them and Nancy to read and write.

In 1852, as he was dying, Henry tried to protect his second family by willing Nancy, who was pregnant with their third child, and their two sons to his legal (white) son and heir Montague Grimké, whose mother was Henry's deceased wife. He directed that they "be treated as members of the family," but Montague never provided well for them. His father acknowledged his sons, although he did not manumit (free) them or make the rest of his family aware of their existence. Archibald's brothers were Francis and John.

Henry was a member of a prominent, large slave-holding family in Charleston. His father and relatives were planters and active in political and social circles. His father’s two youngest sisters, Sarah and Angelina, had been gone from Charleston for years, having joined the Quakers and the American Anti-Slavery Society. His aunt Eliza, the executor of his father's will, allowed them to live as if they were free and did not aid them financially. In 1860, Montague "claimed them as slaves," bringing the boys into his home as servants. Later, he hired both of them as laborers.

After Francis rebelled, Montague Grimké sold him. Archibald ran away and hid with relatives for two years until after the end of the American Civil War. After the war ended, the three Grimké boys attended freedmen's aid society schools, where the teachers recognized their talents. They gained support to send Archibald and Francis to the North. They studied at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. In February 1868, Angelina Grimké Weld read an article in which Edwin Bower, a professor at Lincoln University near Philadelphia, compared Lincoln's all-black student body favorably with any class I have ever had, with special praise for a student named Grimké, who came to the university just out of slavery. Stunned, she investigated and found that Archibald and his siblings were her brother's children. She and Sarah acknowledged the boys and their mother, Nancy Weston, as family and tried to provide them with better opportunities.

They paid for their nephews' education: The Grimkés introduced the young men to their abolitionist circles. The youngest son, John, dropped out of school and returned to the South, losing touch with his brothers. After establishing his law practice in Boston, Massachusetts, Archibald Grimké met and married Sarah Stanley, a white woman from the Midwest. They had a daughter, Angelina Weld Grimké, born in 1880. They separated while their daughter was young, and Stanley returned with Angelina to the Midwest when the girl was three. When Angelina was seven, Stanley started working. She brought Angelina back to her father in Boston. The couple never reconciled, and Stanley never saw her daughter again; she committed suicide by poison in 1898.

In 1894, Grimké was appointed as consul to the Dominican Republic. While he was in Central America, his daughter Angelina lived for years with his brother Francis and his wife Charlotte in Washington, DC, where Francis was minister of the 15th Street Presbyterian Church. After graduating from school, she became a teacher and writer. The Crisis Magazine of the NAACP published her essays and poetry. In 1916, she wrote the play Rachel, which addressed lynching, in response to a call by the NAACP for works to protest the controversial film, The Birth of a Nation. In addition, she wrote poetry, some of which is now considered the first Black lesbian work. rimké lived and worked in the Boston area for most of his career.

Beginning in the 1880s, he began to get active in politics and speak out about the rise of white supremacy following the end of Reconstruction in the South. He was appointed as editor of the Hub, a Republican newspaper that tried to attract black readers. rimké supported equal rights for blacks in the paper and public lectures, which were popular in the nineteenth century. He became increasingly active in politics and was chosen for the Republican Party's state convention in 1884. That year, he was also appointed to the state hospital board for the insane. rimké became involved in the women's rights movement, which his aunts supported. She was elected as president of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. Believing that the Republicans were not doing enough, he left the party in 1886. In 1889, he joined the staff of the Boston Herald as an exceptional writer.

In the South, the situation for Blacks was deteriorating, and Grimké continued the struggle against American racism, allying at times with other major leaders of the day. They had also become involved in Frederick Douglass' National Council of Colored People, a predecessor to the NAACP, which grappled with education issues for blacks, especially in the South. rimké disagreed with Booker T. Washington about emphasizing industrial and agricultural education for freedmen (the South still had a primarily agricultural economy). He believed there needed to be academic and higher education opportunities, similar to his own. In 1901, he and other men started The Guardian newspaper and selected William Monroe Trotter as editor. Together, Grimké and Trotter also organized the Boston Literary and Historical Association, which at the time was a gathering of men opposed to Washington's views, but Grimké continued to make his way.

Despite the earlier conflict with Washington and his followers, in 1905, Grimké started writing for the New York Age, allied with Washington. He wrote about national issues from his point of view, urging more activism and criticizing President Theodore Roosevelt for failing to adequately support Black troops in Brownsville, Texas, where they were accused of starting a riot. Continuing his interest in intellectual work, he served as president of the American Negro Academy from 1903 to 1919, which supported Black scholars and promoted higher education. He published several papers with them, dealing with issues of the day, such as his analysis in "Modern Industrialism and the Negroes of the United States" (1908). They believed that capitalism, as practiced in the United States, could help freedmen who left agriculture to achieve independence and true freedom. In 1907, he became involved with the Niagara Movement. They struggled to find the best way to deal with racism and advance equal rights at a time when the lynching of Blacks in the South continued.

After his daughter graduated from college, Grimké became increasingly active as a leader in the NAACP. First, he was active in Boston, writing letters in protest of proposed legislation in Washington, DC., to prohibit interracial marriages. The legislation was not passed.) In 1913, he was recruited by national leaders to become the president of the Washington, DC, branch and moved to the capital with his daughter. His brother Francis and his wife Charlotte still lived there. Grimké led the public protest in Washington, D.C., against the segregation of federal offices under President Woodrow Wilson, who acceded to the wishes of other Southerners in his cabinet. Gimké testified before Congress against it in 1914 but failed to gain changes. A few years ago, he also became a national vice president of the NAACP. The organization supported the US in World War I, but Grimké highlighted the racial discrimination against Blacks in the military and worked to change it. In 1919, the NAACP awarded him the Spingarn Medal for his life's work for racial equality.

He fell ill in 1928. At the time, he and Angelina lived with his brother Francis, a widower. His daughter and brother cared for him until his death on February 25, 1930. In 1934, the Phelps Colored Vocational School was renamed Grimké Elementary School in his honor. The school was closed in 1989, and the building served as headquarters for the Washington D.C. Fire and Corrections Departments until 2012, when the main building was left vacant. The gymnasium has housed the African American Civil War Museum since 2010.