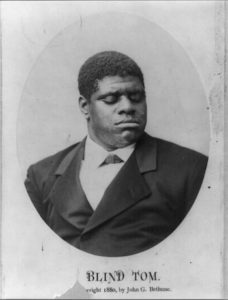

Blind Tom

Blind Tom Wiggins, a Black composer and pianist, was born on this date in 1849.

From Columbus, GA., he was born with a condition that today's doctors might diagnose as "autistic savant,” one of only about 100 cases recorded in medical history. James Bethune of Columbus, Georgia, purchased Tom’s father, Domingo Wiggins, a field slave, and his mother, Charity Greene, at auction when young Tom was an infant. Because he was the blind (disabled) sickly "pickaninny," and had no labor potential, he was thrown into the sale as a no-cost extra. Although Tom's parents were married, the prevailing custom of the time dictated that female slaves and their children retain the names of their owners; hence, the name Thomas Greene Bethune. Bethune was a white veteran of the Mexican War, a practicing lawyer, and a newspaper editor at the Columbus Times.

For the first several years of his life, his only sign of human intelligence was his interest in sounds and his ability to imitate them. Charity was allowed to bring Tom to the main house where she worked for the Bethune family, a family of seven musically talented children who overflowed their home with singing and piano playing. When the Bethune children practiced their piano lessons, Tom listened. Once given access to the keyboard, Tom astounded the family. With his small hands and fingers, he could reproduce the sequence of chords from his memory exactly as he had heard them played. By the age of six, Tom had begun improvising on the piano and composing his own musical pieces. He would claim that the wind, rain, or the birds had taught him the melody. Even though a local music teacher told Bethune that Tom's musical abilities were beyond comprehension and his best course of action was to let him hear fine playing, Bethune provided Tom with various music instructors.

One of Tom's music teachers later reported that Tom could learn skills in a few hours that required other musicians years to perfect. In October 1857, "Blind Tom" performed before a large audience, with difficulty comprehending how a blind slave child could master the piano keyboard. Slaves with musical talent meant income for their owners, and in 1858, James Bethune "hired out" Tom to concert promoter Perry Oliver for several years. It has been estimated that Bethune pocketed $15,000 from the arrangement and that Perry Oliver made profits amounting to $50,000. Now, at the age of nine, Tom was separated from his family and toured hundreds of cities on a rigorous four-show-per-day schedule. Not only could Tom perform world classics, he would overwhelm his audiences by turning his back to the piano and giving an exact repetition, a reversal of the keys the left and right hands played.

Musicians in the audience were invited to challenge him musically. Tom could reproduce on the keyboard any music a challenger would first perform. Taking that feat one step further, he could play a perfect bass accompaniment to the treble played by someone beside him, the first time he played it. Tom would often push the other performer aside and repeat the entire composition alone. When audiences applauded, Tom followed suit, impersonating the sounds of approval.

One of the earliest concert reviews published in the Baltimore Sun on June 27, 1860, announced to its readers that Tom was a phenomenon in the musical world, "thrusting all our conceptions of the science to the wall and informing us that there is a musical world of which we know nothing." A command performance before President Buchanan at the White House drew further attention, and the press referred to him as the greatest pianist of the age, whose skills surpassed Mozart. In January 1861, Perry Oliver and Tom were in New York when news broke of Georgia's secession from the Union. Canceling further New York engagements, Perry Oliver and Tom retreated, and Tom's talents would be used in the South, giving concerts for Confederate soldiers and raising money for the Southern cause.

After the Battle of Manassas, Tom and his manager were confined in Nashville for several months, and after hearing the battle discussed for several weeks, Tom sat down at the piano and produced a composition incorporating melodies representing the Union Army, the Confederate Army, and Confederate and Union leaders Beauregard and McDowell. The composition became a popular signature piece and a favorite with concert audiences in the South. In 1862, General Bethune took up managing and traveling with Tom, always attempting to keep far south of the Union army lines and out of the line of fire. Noted writers such as Rebecca Harding Davis kept the word of Blind Tom alive in the North. They fascinated readers of the prestigious Atlantic Monthly with a report on Tom's abilities.

Foreseeing that the South would soon fall to Union domination, General Bethune arranged for Domingo and Charity to sign a contract giving him the management of Tom until he reached 21. Tom would receive food, shelter, musical instruction, and a $20 monthly allowance. The surviving parents would receive $500 a year plus food and shelter. Bethune would retain over 90 percent of the remaining profits from Tom's performances. Conservative estimates place that amount at $18,000 a year. After the War’s end, Tom was dispatched on another tour, which included appearances in major cities of the Northern states. One of the first in New Albany, IN, became a monumental news event.

Tabbs Gross, a Negro entertainment promoter sometimes described as the nation's Black P. T. Barnum, came forward, claiming Bethune had accepted his down payment toward an agreed upon $20,000 in gold for possession of Blind Tom. He further claimed Bethune later changed his mind without returning his full payment. With Tom in tow, the Bethune entourage hastily exited New Albany and fled to Ohio. Tabbs Gross and his lawyer pursued the Bethunes into Ohio. The civil case for ownership of Blind Tom's services came to court in Cincinnati, drawing a flurry of newspaper attention that lasted well over a week in July 1865. In this case, of a Black man pitted against a White man for possession of a Negro youngster, the judge rendered the decision in favor of Bethune.

On July 30, 1887, a federal court ordered General Bethune to surrender Tom at Arlington, VA, to Charity and the General’s former daughter-in-law, Eliza Bethune. Newspapers reported that Tom, disappointed and grief-stricken at the thought of leaving Virginia and the old General, was threatening to "fight them all." On the surrender date, General Bethune's son, James, brought Tom to the courtroom. The family, which had made a fortune estimated at $750,000 at the hands of Blind Tom, gave possession of him over to his mother, Charity, a mother he hardly knew. Tom, who brought with him nothing more than his wardrobe and a silver flute, offered no resistance when he boarded the train to leave Virginia for New York and home with Eliza.

One month later, Tom was again on the concert stage, showing no signs of emotional trauma from his latest custody battle. Now a source of income for Eliza, who promoted him as "the last slave set free by order of the Supreme Court of the United States," Tom's performances continued throughout the United States and Canada. He now performed under his father's surname, Thomas Greene Wiggins. Except for his brief reunion with Charity, who soon returned to Georgia, nothing else had changed. Tom spent the remainder of his life in the care of Eliza, continuing to perform, give concerts, and stage vaudeville acts until 1904.

His last days were spent in seclusion, playing the piano and holding imaginary receptions. Tom died at age 59 on June 13, 1908, at Eliza's home in Hoboken. Mystery surrounds Blind Tom's final resting place. Some historians related that in a final victory for custody of Tom, 20 years after his death, Fannie Bethune, the youngest surviving daughter of James Bethune, received permission to move Tom's body back to his old home in Georgia. They give his final resting place as the old Westmoreland Plantation just outside Columbus, GA, where a historical marker has been erected.

In 1992. Geneva H. Southall wrote three books on his life. Musician John Davis, who released a CD of Tom's music in 2000, claims that an examination of cemetery records at Evergreens Cemetery in New York indicates the body was never moved from its original unmarked grave. Thus, the controversy surrounding Blind Tom continues into the 21st century.