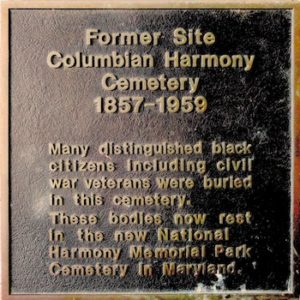

Headstone

*On this date in 1859, celebrate the Columbian Harmony Cemetery. This was an African American cemetery.

It was constructed as the successor to the smaller Harmoneon Cemetery, which formerly existed at 9th Street NE and Rhode Island Avenue NE in downtown Washington, D.C. In its beginning, the Columbian Harmony Society was a mutual aid society formed on November 25, 1825, by free African Americans to assist other Blacks. On April 7, 1828, it established the "Harmoneon," a cemetery exclusively for members of the society. This was a 1.3-acre cemetery bounded by 5th Street NW, 6th Street NW, S Street NW, and Boundary Street NW. Burials began in 1829.

On June 5, 1852, the Council of the City of Washington in the District of Columbia passed a local ordinance that barred the creation of new cemeteries anywhere within Georgetown or the area bounded by Boundary Street (northwest and northeast), 15th Street (east), East Capitol Street, the Anacostia River, the Potomac River, and Rock Creek. Several new cemeteries were therefore established in the "rural" areas surrounding Washington: Columbian Harmony Cemetery in D.C.; Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Silver Spring, Maryland; Glenwood Cemetery in D.C.; Mount Olivet Cemetery in D.C.; and Woodlawn Cemetery in D.C. As Harmoneon quickly filled, the society was forced to find new burial grounds.

On July 1, 1857, it acquired 17 acres bounded by Rhode Island Avenue NE, Brentwood Road NE, T Street NE, and the railroad tracks of the Capital Subdivision of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Transferal of graves was completed in 1859. It sold the old Harmonium site for $4,000. An 18-acre (73,000 m2) tract adjacent to the Columbian Harmony Cemetery was purchased in the summer of 1886. From the early 1880s to the 1920s, Columbian Harmony Cemetery was Washington's most active Black cemetery, with 21.8 percent of all African American burials occurring there. It never ranked lower than fourth in total African American burials, and between 1892 and 1919, it was number one in every year but one. In 1895 alone, one-third of Washington's blacks were buried there.

Columbian Harmony Cemetery was filling so rapidly that its owners considered purchasing a new cemetery outside the District of Columbia. By 1901, it held 10,000 graves. They were among the "big five" of Black cemeteries in the District of Columbia. By 1900, landscaping and roads had been added throughout the cemetery. A chapel was built in 1899, and a caretaker's lodge in 1912. In 1929, the society purchased 44.75 acres near Landover, Maryland, for $18,000. Some of the owners of existing burial plots sued in 1949 to prevent the relocation of graves. Although some burials occurred at the new cemetery, no grave relocations occurred. In 1950, the society stopped new burials at Columbian Harmony Cemetery. By this time, at least 400 Black veterans, nearly all of them former United States Colored Troops, were buried there.

In 1953, the society relocated the few graves at Huntsville to a nearby cemetery and sold its property for $178,000 to a real estate development company. A lack of new burials left the cemetery in a difficult financial situation. The graveyard was experiencing an annual loss of $3,000. In 1957, real-estate investor Louis N. Bell offered to buy the Columbian Harmony Cemetery. Bell informed the society that he would expand his 107.5 acres of Forest Lawn Cemetery (near the society's former property in Landover) by 65 acres. He offered the society a 25 percent stake in the new cemetery and to pay all relocation costs in exchange for the property in D.C. Although the society rejected this offer, negotiations continued. Bell eventually agreed to establish a perpetual care fund, designate a 30-acre section of the cemetery as the "Harmony Section," and allow the society to appoint half of the board of the new cemetery association. All graves in the cemetery were moved to National Harmony Memorial Park in Landover, Maryland, in 1959.

The cemetery site was sold to developers, and a portion was used for the Rhode Island Avenue – Brentwood Washington Metro station. In May of 1960, approximately 37,000 graves were moved to National Harmony Memorial Park. The District of Columbia Department of Health had to draft and obtain approval for a new set of regulations to govern the relocations. A D.C. district court agreed to issue a single exhumation order rather than review thousands of cases. All the heirs of those buried at Columbia Harmony Cemetery were contacted, and their permission to move the graves was secured. More than 100 workers exhumed, recreated in new coffins, moved, and reburied the dead. The reinterments were completed on November 17, 1960. It was the most significant cemetery move in the nation's capital and cost $1 million.

When the Rhode Island Avenue – Brentwood Metro station was constructed in 1976, workers discovered that not all the bodies had been exhumed. At least five coffins and numerous bones were unearthed. A plaque was affixed to a column near one of the station's entrances to commemorate the former cemetery. When a parking lot at the site was renovated in 1979, more bones, bits of cloth, and coffins were unearthed. The relocation agreement did not cover the existing memorials and monuments. According to the Maryland Historical Trust, none of the original grave markers were retained.

Furthermore, most of the remains at Columbian Harmony Cemetery were transferred and reburied without identifying which person was being reburied. Grave markers were sold as scrap. The fate of many of the original markers remained a mystery for almost a half-century. In 2009, hikers found many headstones in the riprap lining the banks of the Potomac River on privately owned land near Caledon State Park in King George County, Virginia.

Virginia State Senator Richard Stuart, who bought the land in 2016, enlisted Virginia historians to trace the origin of the headstones; they were determined to have come from Columbian Harmony. Because the headstones were adjacent to the state park, the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation could only turn them over to a nonprofit. With the assistance of Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, an agreement was signed by the states of Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, as well as the History, Arts, and Science Action Network (HASAN), a nonprofit based in Lynchburg, Virginia.

The grave markers will be turned over to the nonprofit, and National Harmony has agreed to allow the nonprofit to place them on the appropriate graves at the cemetery. The two organizations are also collaborating to create a memorial garden located within the cemetery's main gate. Stuart said he will work to create a parklike memorial along the Potomac to recognize any headstones that cannot be reclaimed. The government of the District of Columbia said it would assist in researching the history of those buried in Columbian Harmony.