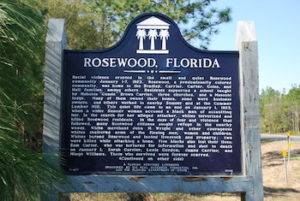

Historic Marker

*On this date in 1923, the Rosewood Massacre occurred. The Rosewood Massacre was a racially motivated slaughter of Black people and destruction of a Black town that took place in rural Levy County, Florida.

Eyewitness accounts suggested a higher death toll of 27 to 150. Rosewood was originally settled in 1845 by both Blacks and whites. Black Codes and Jim Crow laws in the years after the American Civil War advanced segregation in Rosewood (and much of the South). Pencil factories provided employment, but the cedar tree population soon became decimated, and white families moved away in the 1890s to the nearby town of Sumner. By the 1920s, Rosewood’s population of about 200 comprised Black citizens, except for one white family that ran the general store there. On New Year’s Day 1923, in Sumner, Florida, (then) 22-year-old Fannie Taylor (image) was heard screaming by a neighbor. The neighbor found Taylor covered in bruises and claimed a Black man had entered the house and assaulted her.

The incident was reported to Sheriff Robert Elias Walker; Taylor said she had not been raped. Fannie Taylor’s husband, James, a foreman at the local mill, escalated the situation by gathering an angry mob of white citizens to hunt down the culprit. He also called for help from white residents in neighboring counties, among them a group of about 500 Ku Klux Klan members who were in Gainesville for a rally. The town of Rosewood was destroyed in what contemporary news reports characterized as a race riot. Florida had an especially high number of lynchings of Black men in the years before the massacre, including a well-publicized incident in December 1922. Before the killings, the town of Rosewood had been a quiet, self-sufficient whistle-stop on the Seaboard Air Line Railway. During the massacre, a mob of several hundred whites combed the countryside, hunting for Black people, and burned almost every structure in Rosewood. Survivors from the town hid for several days in nearby swamps until they were evacuated by train and car to larger towns.

No arrests were made for what happened in Rosewood. The town was abandoned by its former black and white residents; none ever moved back, none were ever compensated for their land, and the town ceased to exist. Although the rioting was widely reported around the United States, few official records documented the event. Survivors, their descendants, and the perpetrators remained silent about Rosewood for decades. Sixty years after the rioting, the story of Rosewood was revived in major media when several journalists covered it in the early 1980s. Survivors and their descendants organized to sue the state for having failed to protect Rosewood's Black community. In 1993, the Florida Legislature commissioned a report on the incident. As a result of the findings, Florida became the first U.S. state to compensate survivors and their descendants for damages incurred because of racial violence.

The incident was the subject of a 1997 feature film directed by John Singleton. In 2004, the state designated the site of Rosewood as a Florida Heritage Landmark. A marker on State Road 24 names the victims and describes the community's destruction. Scattered structures remain within the community, including a church, a business, and a few homes, notably John Wright's. Mary Hall Daniels, the last known survivor of the massacre, died at the age of 98 in Jacksonville, Florida, on May 2, 2018. Rosewood descendants formed the Rosewood Heritage Foundation and the Real Rosewood Foundation to educate people both in Florida and all over the world about the massacre.

The Rosewood Heritage Foundation created a traveling exhibit that tours internationally to share the history of Rosewood and the attacks; a permanent display is housed in the library of Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach. The Real Rosewood Foundation presents various humanitarian awards to people in Central Florida who help preserve Rosewood's history. The organization also recognized Rosewood residents who protected Blacks during the attacks by presenting an Unsung Heroes Award to the descendants of Sheriff Robert Walker, John Bryce, and William Bryce.