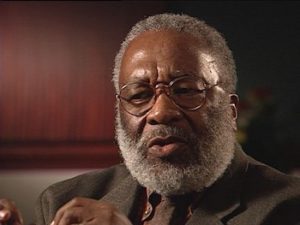

Vincent G. Harding

*Vincent Harding was born on this date in 1931. He was a Black historian, author, and educator.

From Harlem, New York, his mother, Mabel Lydia Broome, a domestic worker, reared Vincent Gordon Harding. They moved to the Bronx when he was a youth, and he graduated from Morris High School. He received a bachelor’s degree in history from the City College of New York and a master’s in journalism from Columbia. After serving in the Army, which made him a committed pacifist, he earned a master’s degree in history from the University of Chicago, followed by a PhD in history. He wrote his dissertation on Lyman Beecher, a Protestant minister, antislavery advocate, and father of Henry Ward Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Harding also served as a lay pastor in the Mennonite Church in Chicago. In the late 1950s, as a church representative, he traveled to the South to observe the state of race relations there. On that trip, he met Dr. King and became deeply influenced by him. In the early ’60s, Harding and his wife, Rosemarie Freeney, moved to Atlanta, where they established Mennonite House, an integrated community center. The site they secured happened to be the childhood home of the soprano Mattiwilda Dobbs, one of the first Black singers to perform with the Metropolitan Opera. In Atlanta, he joined the Department of History and Sociology at Spelman College, where he became the department chairman. At the same time, he contributed speeches for Dr. King.

His most memorable one, described in 2007 by Sojourners, the progressive Christian magazine, as “one of the most important speeches in American history,” was commissioned amid the United States’ escalating involvement in Vietnam. “He wanted to make a clear statement on the issue, but he didn’t have the time to craft something of that depth and intensity because of his travel schedule,” Harding said in a 2013 interview. “So he asked me because I knew who he was and where he came from.”

Dr. King delivered the addresses “Beyond Vietnam” and “A Time to Break Silence, at Riverside Church in Manhattan on April 4, 1967. “A time comes when silence is betrayal,” he said. “And that time has come for us in relation to Vietnam.” He added: “If we continue, there will be no doubt in my mind and in the mind of the world that we have no honorable intentions in Vietnam. If we do not stop our war against the people of Vietnam immediately, the world will be left with no other alternative than to see this as some horrible, clumsy, and deadly game we have decided to play.”

The speech, which articulated what was then a relatively unpopular position, touched off a firestorm. In an editorial titled “Dr. King’s Disservice to His Cause,” Life magazine called it “a demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi.” The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People described the address as “a serious tactical error.”

After Dr. King’s death, Harding became the director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Center, a post he held until 1970. He later directed the Institute of the Black World, an organization based in Atlanta that promotes black studies and intellectual life. Harding taught at Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania before joining the faculty at Iliff in 1981. There, he and his wife established the Veterans of Hope Project, which documents the stories of social justice leaders worldwide on video.

As an author, He was known in particular for two books, “There Is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America” (1981) and “Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero” (1996). His other books include “The Other American Revolution” (1980) and “Hope and History” (1990). His wife, Rosemarie Harding, died in 2004. In “Martin Luther King,” Harding argued that, toward the end of his life, Dr. King's focus on social imperatives, such as eradicating war and poverty, made him more radical than many Americans feel secure in acknowledging. “Men do not get assassinated for wanting children of different colors to hold hands on a mountainside,” Dr. Harding said in a 2005 lecture. “He told us to march on segregated housing, segregated schools, poverty, and the military with more support than social programs. That’s where he was in 1965. If we let him go where he was going, he becomes a challenge, not a comfort.”

Harding worked at the center of race, religion, and social responsibility for over half a century. Though he was not as high-profile a figure as some of his contemporaries, he preferred to work mainly behind the scenes; he was a central figure in the civil rights movement. A friend, adviser, and sometime speechwriter to Dr. King, Dr. Harding was a member of the cohort that helped carry on his mission after his assassination in 1968. Harding, the first director of what is now the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, was at the forefront of promoting Black studies as an academic discipline at colleges and universities throughout the country. He was a consultant to television programs about the Black experience, notably “Eyes on the Prize,” the documentary series first broadcast on PBS in 1987.

For the entire furor surrounding “A Time to Break Silence,” neither Harding nor King disavowed the address. However, he would come to have profound regrets about having composed it for Dr. King in the first place. “It was precisely one year to the day after this speech that that bullet which had been chasing him for a long time finally caught up with him,” Harding said in a 2010 interview. “And I am convinced that that bullet had something to do with that speech. And that’s been quite a struggle for me over the years.”

Vincent Harding, a historian, author, and activist who wrote one of the most polarizing speeches ever given by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., died from an aneurysm on May 19, 2014, in Philadelphia. He was 82. Harding’s survivors include his second wife, Aljosie Aldrich Harding, whom he married in December 2013; a daughter, Rachel Harding; and a son, Jonathan.