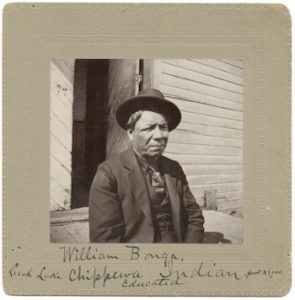

William Bonga

*The birth of William Bonga is celebrated on this date in 1850. He was a Black Ojibwe trader and interpreter.

William Bonga grew up near the government establishment at Leech Lake Reservation in Minnesota. His father, George Bonga, was superintendent of the government farm. He attended school there with his younger sister, Susie, while his older brother, James, worked as a farmhand. Young William was coming of age after the massive land cessions of the 1855 Treaty of La Pointe put an end to the fur trade economy. In 1866, he was 16 years old when the first permanent agency buildings went up at Leech Lake.

By the 1860s, his father had left the farm and entered the mercantile business. Brother James was working for him as a clerk. In 1868, corrupt government agent Charles Ruffee, with his associates John G. Morrison and Clement Beaulieu, hired a group of Leech Lake warriors to assassinate the famous Gull Lake chief, Gwiiwizens (Hole-in-the-Day II). The head Chief at Leech Lake, Nigone Benais (Flat Mouth II), refused to hand the assassin warriors over to authorities.

As a member of Nigone Benais’ band, these events must have formed a lasting impression on William. In 1870, he and another former fur trader’s son were boarding with Sela Wright’s wife at her home in Lorain, Ohio, while attending Oberlin College. Sela G. Wright, who oversaw the farm, had been sent by a missionary outcropping of Oberlin, a liberal arts university that promoted the abolition of slavery.

Returning to Leech Lake, Bonga found a growing lumber town with a hotel and tavern. It was overrun with civil engineers in the planning stages of building a series of dams that would aid the transport of lumber while flooding Anishinaabe subsistence resources. While this was developing, he married Enimwekway (Nettie), and they had their first child, Equasaince, the same year his father died (1874). The couple had three more children, Odanah (Mary) in 1877, Simon John in 1880, and Joseph in 1885. That same year, tensions over the government dams became a crisis with plots to assassinate Nigone Benais, which drove him out of town.

Bonga said he would “raise the tomahawk” if the issue were not settled, possibly in his role as a private in the newly appointed Indian police force. His mother died in 1889, and his family joined the Leech Lake tribe, which accepted allotments at White Earth. Joining Waabaanakwad’s (Chief White Cloud AKA D.G. Wright) advance guard of 1868, William moved his family to White Earth in 1890, although they did not inhabit the allotted plots until 1900. From 1890 for the rest of his life, Bonga lived and worked at White Earth with his wife and children, close to the Indian agency and surrounded by other prominent Anishinaabe and métis families, such as the Wrights, Warrens, Roys, and Bellangers.

Now a government interpreter, he wrote numerous letters advocating Anishinaabe’s treaty rights. In 1899, he and his cousin Paul Bonga were interpreters for a delegation to Washington led by Nigone Benais. The latter had returned to Leech Lake in the aftermath of the Bear Island War, in which an estimated handful of Anishinaabe warriors triumphed over three hundred US armed forces. Ethnically Anishinaabe or métis, the major culture wars of his lifetime were those among Anishinaabek, métis, and whites, not between whites and blacks. William Bonga died in 1909.

William Bonga (1850-1909) – A Life Among the Reservation Elite, by Cory Willmott