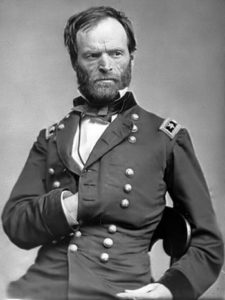

William T. Sherman

*William T. Sherman, a white American soldier, businessman, educator, and author, was born on this date in 1820.

William Tecumseh Sherman was born in Lancaster, Ohio, near the banks of the Hocking River. His father, Charles Robert Sherman, a lawyer who sat on the Ohio Supreme Court, died of typhoid fever in 1829. He left his widow, Mary Hoyt Sherman, with eleven children and no inheritance. After his father's death, the nine-year-old Sherman was raised by a Lancaster neighbor and family friend, attorney Thomas Ewing. Sherman's older brother became a federal judge.

One of his younger brothers was a founder of the Republican Party, and another was a banker. Sherman graduated from West Point in 1840. He interrupted his military career in 1853 to pursue private business ventures without much success.

In 1859, he became superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy (now Louisiana State University), a position he resigned from when Louisiana seceded from the Union. Sherman commanded a brigade of volunteers at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861 before being transferred to the Western Theater.

Stationed in Kentucky, his pessimism about the outlook of the American Civil War led to a breakdown that required him to be briefly put on leave. He recovered by forging a close partnership with General Ulysses S. Grant. He served under Grant in 1862 and 1863 in the battles that culminated with the Confederate armies' routing in Tennessee. 1864 Sherman succeeded Grant as the Union commander in the Western Theater. He led the capture of the strategic city of Atlanta, a military success that contributed to the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln. Sherman's march through Georgia and the Carolinas involved little fighting but large-scale destruction of cotton plantations and other infrastructure, a systematic policy intended to undermine the ability and willingness of the Confederacy to continue fighting.

Sherman accepted the surrender of all the Confederate armies in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida in April 1865. Still, the terms he negotiated were considered too generous by U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who ordered General Grant to modify them. Before the war, Sherman was not an abolitionist and did not believe in "Negro equality." Before the war, Sherman expressed some sympathy with the view of Southern whites that the black race was benefiting from slavery. However, he opposed breaking up slave families and advocated that the laws forbidding the education of enslaved people be repealed. Sherman declined to employ black troops in his armies throughout the war. In his Memoirs, Sherman commented on the political pressures of 1864–1865 to encourage the escape of enslaved people, in part to avoid the possibility that "able-bodied slaves will be called into the military service of the rebels ."

Sherman rejected this, arguing that focusing on such policies would have delayed the "successful end" of the war and the "[liberation of] all slaves ."Tens of thousands of escaped enslaved people nonetheless joined Sherman's marches through Georgia and the Carolinas as refugees, and their fate soon became a pressing military and political issue. Some abolitionists accused Sherman of doing little to alleviate the precarious living conditions of these refugees, motivating Secretary of War Stanton to travel to Georgia in January 1865 to investigate the situation. On January 12, Sherman and Stanton met in Savannah with twenty local Black leaders, most Baptist or Methodist ministers, invited by Sherman. According to historian Eric Foner, "the 'Colloquy' between Sherman, Stanton, and the Black leaders offered a lens through which the experience of slavery and the aspirations that would help to shape Reconstruction came into sharp focus."

After Sherman's departure, the spokesman for the black leaders, Baptist minister Garrison Frazier, declared in response to Stanton's inquiry about the feelings of the black community: "We looked upon General Sherman before his arrival as a man in the providence of God specially set apart to accomplish this work, and we unanimously feel inexpressible gratitude to him, looking upon him as a man that should be honored for the faithful performance of his duty. Some of us called upon him immediately upon his arrival, and it is probable he would not meet the Secretary [Stanton] with more courtesy than he met us. His conduct and deportment toward us characterized him as a friend and a gentleman."

Four days later, Sherman issued his Special Field Orders, No. 15. The orders provided for the settlement of 40,000 formerly enslaved people and black refugees on land confiscated from white landowners in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Sherman appointed Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, an abolitionist from Massachusetts who had previously directed the recruitment of black soldiers, implemented that plan. Those orders, which became the basis of the claim that the Union government had promised formerly enslaved people "forty acres and a mule," were revoked by President Andrew Johnson later that year.

Towards the end of the Civil War, some elements within the Republican Party regarded Sherman as strongly prejudiced against black people. However, Sherman's views on race evolved significantly over time. When Grant became president of the United States in March 1869, Sherman succeeded him as Commanding General of the Army. Sherman served in that capacity from 1869 until 1883 and was responsible for the U.S. Army's engagement in the Indian Wars.

He refused to be drawn into party politics and published his memoirs in 1875, which became one of the best-known first-hand accounts of the Civil War. In 1888, near the end of his life, he published an essay in the North American Review defending the full civil rights of black citizens in the former Confederacy. William Tecumseh Sherman died on February 14, 1891.