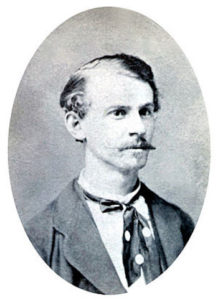

Albert Parsons

*On this date, in 1848, Albert Parsons was born. He was a white-American socialist, newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist.

Albert Richard Parsons was born in Montgomery, Alabama, the tenth child of a shoe and leather factory owner originally from Maine. His parents died when he was a small child, leaving him to be raised by his eldest brother, who was married and the proprietor of a small newspaper in Tyler, Texas. In 1859, at the age of 11, Parsons left his brothers to live with a sister in Waco, Texas. Parsons attended school for about a year before leaving to become an apprentice at the Galveston Daily News.

At the age of 13, Parsons volunteered to fight for the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War of 1861. His unit was the "Lone Star Greys." Parsons' first military exploit was in an artillery company. After his first enlistment, Parsons left Fort Sabine to join the 12th Regiment of the Texas Cavalry and saw battle during three separate campaigns. After the war, Parsons returned to Waco, Texas, and traded his mule for 40 acres of standing corn. He hired former slaves to help with the harvest and netted a sufficient sum to pay for six months' tuition at Waco University, now known as Baylor, a private Baptist University.

After college, Parsons left to work in a printing office before launching his Waco Spectator newspaper in 1868. In his paper, Parsons took the unpopular position of accepting the terms of Reconstruction measures aimed at securing the political rights of former slaves. In this supercharged political atmosphere, Parsons' paper was soon terminated. In 1869, Parsons secured a position as a traveling correspondent and business agent for the Houston Daily Telegraph, where he met Lucy Ella Gonzales, a Black woman. The pair married in 1872, and his wife later became a political activist. In 1870, Parsons was the beneficiary of Republican political patronage when he was appointed Assistant Assessor of the United States Internal Revenue under the administration of Ulysses S. Grant.

He also worked as a secretary of the Texas State Senate before being appointed Chief Deputy Collector of the Internal Revenue at Austin, Texas. In the summer of 1873, Parsons traveled extensively through the Midwestern United States as a representative of the Texas Agriculturalist, getting a broader view of the country and deciding to settle with his wife in Chicago. On May 1, 1886, Parsons, with his wife Lucy and two children, led 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue in what is regarded as the first-ever May Day Parade supporting the eight-hour workday. Parsons addressed a rally at Haymarket Square on May 4. This rally was organized to protest what had happened a few days prior.

Parsons initially declined to speak at the Haymarket, fearing it would cause violence by holding the rally outdoors, but he changed his mind. The mayor of Chicago was also present and noticed that it was a peaceful gathering, but he left when it appeared that rain was imminent. Worried about his children when the weather changed, Parsons, his wife Lucy, and their children left for Zeph's Hall on Lake Street and were followed by several protesters. The event ended around 10 p.m. As the audience began to drift away, the policemen forcefully told the crowd to disperse.

A bomb thrown into the square exploded, killing one policeman and wounding others. Gunfire erupted, resulting in 7 deaths and many others injured. The police also sought Parsons, but he was able to avoid capture, though on the morning of the trial, Parsons arrived in court to stand by his comrades. On November 10, 1887, condemned prisoner Louis Lingg killed himself in his cell with a blasting cap hidden in a cigar. Parsons likely could have had his sentence commuted to life in prison rather than death, but he refused to write the letter asking the governor to do so, as this would be an admission of guilt. The next day, Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel were executed by hanging.