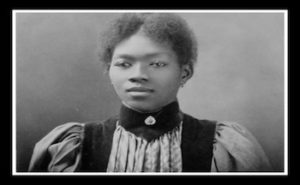

Harriet Wilson

*Harriet Wilson was born on this date in 1825. She was a Black author.

Harriet E. "Hattie" Adams Wilson was born in Milford, New Hampshire, the daughter of Joshua Green, a Black "hooper of barrels," and Margaret Ann (or Adams) Smith, a washerwoman of white-Irish ancestry. Her father died when she was very young, and her mother abandoned her at the farm of Nehemiah Hayward Jr., a well-to-do Milford farmer. As an orphan, Adams was made an indentured servant to the Hayward family, a customary way for society to arrange support at the time. In exchange for her labor, she received room, board, and training in life skills.

After the end of her indenture, Hattie Adams (as she was then known) worked as a house servant and a seamstress in households in southern New Hampshire and central and western Massachusetts. She married Thomas Wilson in Milford on October 6, 1851. Thomas Wilson had been traveling around New England, giving lectures based on his life as an escaped slave, when he met Hattie Adams. Although he continued to lecture in churches and town squares periodically, he soon confided to her that he was never in bondage ("he had never seen the South") and that his "illiterate harangues were humbugs for hungry abolitionists."

Wilson abandoned Harriet soon after they married. Pregnant and ill, Harriet Wilson was sent to the Hillsborough County, New Hampshire Poor Farm in Goffstown, New Hampshire, where her only son, George Mason Wilson, was born in 1852. Soon after George's birth, Thomas Wilson reappeared in her life and took her and her son away from the Poor Farm. Thomas Wilson returned to sea and died soon after. Harriet Wilson returned her son to the care of the Poor Farm.

While working as a dressmaker in Boston, Wilson wrote Our Nig published on September 5, 1859. This was the first known American publication by any Black person. As Wilson explains in the preface, the book was an attempt to get her son back: "Deserted by kindred, disabled by failing health, I am forced to some experiment which shall aid me in maintaining myself and child without extinguishing this feeble life."

Her son died of fever on February 15, 1860, six months after the book's publication. Closer to home, Wilson was active in the organization and maintenance of Children's Progressive Lyceums, the Spiritualist church equivalent to Sunday Schools. She organized Christmas celebrations, participated in skits and playlets, and sometimes sang as part of a quartet at meetings. She was also known for her floral centerpieces and the candies and confectioneries she would make for the children.

When she was not pursuing Spiritualistic activities, Hattie Wilson was employed as a nurse and healer ("clairvoyant physician"). For nearly 20 years, from 1879 to 1897, she was the housekeeper of a boardinghouse in a two-story dwelling at 15 Village Street (near the present corner of Dover [now East Berkeley Street] and Tremont Streets in the South End.) She rented out rooms, collected rent, and provided basic maintenance. Despite Wilson's active and fruitful life after "Our Nig", there is no evidence that she wrote anything else for publication.

On June 28, 1900, "Hattie E. Wilson" died in the Quincy Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts. She was buried in the Cobb family plot in that town's Mount Wollaston Cemetery.

The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience

Editors: Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Copyright 1999

ISBN 0-465-0071-1