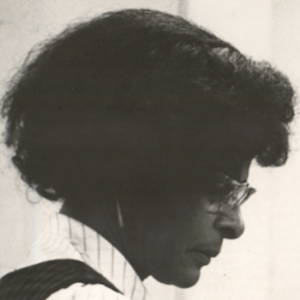

Bernice Robinson

*Bernice Robinson was born on this date in 1914. She was a Black beautician, an activist in the American Civil Rights Movement, and an advocate for education.

Bernice Violanthe Robinson was from Charleston, South Carolina, to Martha Elizabeth (née Anderson) and James C. Robinson. Her mother was a seamstress, and her father was a bricklayer. Robinson was the ninth and youngest child in the family and attended Simonton Elementary School. She attended the segregated Burke Industrial School to the ninth grade; the maximum education allowed for Blacks at that time.

In 1929, she moved to Harlem, NY, to join her older sister, and the following year, she married Thomas Leroy Robinson. She completed her high school education at Wadleigh High School for Girls. When her sister became ill, the girls returned to Charleston, where Robinson had a daughter and divorced before returning to New York in 1936. Back in New York, Robinson found work in the garment district during the day as a seamstress and attended night school at the Poro School of Cosmetology. She eventually opened her beauty salon, and the shop became a meeting place for neighbors, politicians, and activists.

She registered to vote and became politically active for the first time, distributing flyers for a local assembly member. In 1947, Robinson returned to Charleston to care for her aging parents. She opened another beauty shop and, along with her mother, took in sewing. She joined the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) as secretary and chair of the Membership Committee. She used her shop as the center of her activism. In 1955, the United Nations held a workshop on school desegregation, which Robinson attended.

Esau Jenkins and her cousin, Septima Clark, were inspired by the meeting and began to make plans for how they could increase activism on Johns Island. The workshop opened Robinson's eyes for the first time to the problem of illiteracy and the importance of registering voters who could read. Jenkins and Clark convinced a reluctant Robinson that she was the perfect person to run an experimental education program because she lacked formal training as a teacher and would not bring preconceived notions of structure or curriculum. Beauticians were also highly regarded in civil rights work because they enjoyed community respect as entrepreneurs and activists, and were also known for being good listeners. Additionally, they were unlikely to face backlash from white employers, given their status as self-employed individuals. It also helped that Robinson had a good knowledge of the Gullah language spoken on the Island.

Robinson held her first class at the Highlander Folk School on the topic of fundamental human rights on January 7, 1957. Discarding materials for children's education, she taught the students how to read labels on canned goods, fill out paperwork, read newspapers, and perform other tasks they needed for their daily lives. After three months of instruction, the final exam required students to register to vote. Eighty percent of her students passed. The schools became known as Citizenship Schools and sprang up throughout the southern United States after the program was transferred from Highlander to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Robinson continued to volunteer and instruct others as teachers in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee, and became the supervisor of the Low Country Citizenship Schools.

In 1967, she enrolled in a correspondence course in Community Development through the University of Wisconsin–Madison and later completed a similar course in interior design. In 1970, Robinson worked for the South Carolina Commission for Farm Workers (SCCFW), supervising VISTA volunteers. The work focused on the development of daycare and childhood development centers for communities on Edisto Island, Johns Island, Wadmalaw Island, and Yonges Island. Between 1971 and 1973, she directed the creation of the Yonges Island Day Care Center. In both 1972 and 1974, she launched unsuccessful bids for the state House of Representatives as the first Black woman to vie for public office.

In 1975, Robinson returned to the SCCFW to direct programs for migrant workers' day care. She became a loan and relocation officer at the Charleston County Community Development Department in 1979 and held that position until her retirement in 1982. In 1991, Eliot Wigginton published "Refuse to Stand Silently: An Oral History of Grass-Roots Social Activism in America, 1921–1964," which included oral histories from Robinson and other activists involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Robinson's archive of papers was donated to the Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston in 1989.

Bernice Robinson died September 3, 1994, in Charleston, South Carolina. In 2011, Clare Russell conducted a critical review of Robinson's career. In her essay, "A Beautician Without Teacher Training: Bernice Robinson, Citizenship Schools, and Women in the Civil Rights Movement," Russell argues that Robinson has been inadequately studied and her legacy misrepresented. Rather than relying on an untrained teacher, Russell evaluates Robinson based on her extensive education and work experience.