On this date in 1929, 'The All-Negro Hour' premiered on American broadcast radio. It was one of the first radio programs to feature Black performers exclusively.

This article summarizes Black history in American radio broadcasting. Black radio's growth has largely mirrored changes in American culture and the market forces controlling the radio industry. Blacks' growth of economic power has helped transform black radio from a white-dominated advertising medium into a multi-million-dollar industry that gradually became increasingly owned and operated by Blacks.

In the early days of radio, a mixture of positive and negative stereotypes characterized Blacks. Radio shows such as "Beulah" and "Amos and Andy," which evolved into television, featured Black characters that were carefree, inarticulate, and inept. Radio broadcasts by bandleader Duke Ellington, singer Paul Robeson, and others exposed predominantly white radio audiences to the work of talented and refined Black artists. Such images of Blacks frequently appeared in early radio broadcasts, yet a space existed for Blacks in management and ownership positions. Radio shows did not have black announcers, actors, or masters of ceremonies.

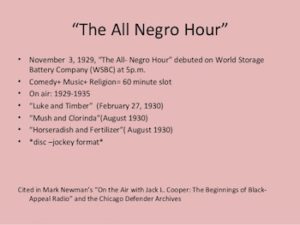

On November 3, 1929, white-owned radio station WSBC in Chicago premiered "The All-Negro Hour," the first radio program to feature Black performers exclusively. The program, hosted by former vaudeville performer Jack L. Cooper, featured music, comedy, and serial dramas. "The All-Negro Hour went off the air in 1935, but Cooper continued to host and produce Black-oriented programming for WSBC. One such program was "Search for Missing Persons," a series launched in 1938 that reunited black migrants from the South with lost friends and relatives. This success and a general trend toward expansion in the radio industry led to a rise of black-oriented radio stations following World War II.

In 1949, station WDIA in Memphis, Tennessee, became the first to employ an all-Black on-air announcing staff. Later that year, WERD in Atlanta began broadcasting as the first Black-owned radio station. Powerful AM stations such as WLAC in Nashville began broadcasting Black-oriented news and "rhythm and blues" music across entire regions of the United States, drawing both black and white audiences.

Institutional racism and a shortage of capital, however, continued to discourage black entrepreneurs from investing in radio broadcasting. Blacks would not make substantial inroads into radio ownership and management until the 1970s. Black radio continued emphasizing news, public affairs, and music after World War II.

"Listen Chicago," the first news discussion program aimed at African Americans, debuted in 1946 and ran until 1952. It focused on Black issues, including church and social news. Black disc jockeys developed colorful on-air personalities that mirrored changes in the black community. "Rhythm and Blues" programs hosted by Black disc jockeys attracted more white listeners after World War II, and the exposure of white kids to Black urban music began to change American society. Black radio fueled the popularity of rock-and-roll and was instrumental in lowering cultural barriers between blacks and whites in the 1950s. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the presence and influence of African American on-air personalities dominated Black radio.

From our African oral tradition, black disc jockeys shaped black (and often white) musical tastes. This broader media perspective created a social grapevine that contributed largely to the empowerment of the growing American civil rights movement. Southern black stations, in particular, became clearinghouses for information and forums for discussion among black communities cut off by segregation and geography. Black radio personalities such as Jack "The Rapper" Gibson of WERD and Tall Paul White of WEDR in Birmingham drew praise from Martin Luther King and other prominent black leaders for their contributions to American Civil Rights efforts.

During this time, many black disc jockeys became caught up in the backlash that followed the civil rights advances and cultural changes. Some also lost their jobs to the "payola" scandal that implicated announcers for receiving cash payments from recording companies in exchange for playing certain records on the air. Also, by the late 1950s, white rock-and-roll "DJs" such as Dewey Phillips and Wolfman Jack were imitating black styles to gain ratings. Following the scandal, station managers increasingly resorted to standardized formats and playlists that restricted the freedom and influence of disc jockeys. Yet, Black radio continued to emphasize individual personalities throughout the 1960s, as DJs such as Purvis Spann in Chicago and Magnificent Montague in Los Angeles echoed the emerging militancy of Black youth and acted as peacemakers during inner-city riots.

The 1970s marked a period of dramatic change in African American radio. Some of this change occurred due to industry-wide trends: formats de-emphasized the news and public affairs programming that had become a staple of Black radio. The emergence of FM radio, with its "more music, less talk" philosophy, intensified the trend away from news and discussion shows that targeted black audiences. During this time, the most significant change in black radio was the increase in the number of black-owned radio stations, which grew from 16 to 88, closing somewhat the wide gap between black-owned stations and stations broadcasting black-oriented programming. The 1970s also saw the emergence of two black-owned and operated radio networks: the Mutual Black Network (which became the Sheridan Broadcasting Network in 1979) in 1972 and the National Black Network in 1973.

Black-owned networks contributed to the standardization common in African American radio and critically acclaimed news and public affairs programming. This helped the transition of black radio into the FM medium by promoting innovative formats such as urban contemporary (UC), appealing to mass, interracial audiences. Urban Contemporary is the best proof that radio waves can cross boundaries. This format attracts substantial numbers of Black, Hispanic, and white listeners. The late Frankie Crocker coined the name Urban Contemporary.

By the 1980s, the Sheridan and National networks claimed a combined audience of over 10 million listeners, and UC stations held the top rating shares in many major U.S. cities. Black-owned radio stations and stations catering to predominantly black audiences increased toward the end of the 20th century.

By 1990, 206 of approximately 600 black-oriented stations were owned by blacks, an ongoing disparity within the radio industry. Black radio, like American society and culture, had undergone dramatic changes since the end of World War II but continued to rely largely upon the music, news, and talk programming that popularized the format in its early years. The National Telecommunications and Information Administration's August 1998 survey of minority ownership of full-power commercial radio and television stations in the United States indicates that Black radio and television ownership is around 1.7 percent.

Blacks own about 168 of 10,315 commercial AM and FM radio stations in the United States. These stations are concentrated in the country's southern region and distributed among 30 states. Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana have the largest number of black-owned stations. Blacks own about 100 (2.1%) of 4,724 commercial AM radio stations in the United States. Blacks currently own 68 (1.2%) of 5,591 commercial FM radio stations in the United States. Ownership of Black-owned FM radio stations had its greatest losses in Indiana and South Carolina and its greatest gains in Louisiana.

Black broadcast medium ownership has historically been a challenge for equity, as minorities have never owned more than 3 percent of U.S. media. Today, minorities, including white women, own just 1.8 percent of broadcasting! The black radio station, locally owned and responsive to local activists, is all but extinct, as are stand-alone stations.

However, Cathy Hughes, Radio One, Inc.'s CEO, is a breath of fresh entrepreneurial air. This African American woman owns the nation's seventh-largest radio broadcasting company (based on 2003 net broadcast revenue) and is the largest company that primarily targets African American and urban listeners. Radio One owns and/or operates 69 radio stations in 22 urban markets in the United States, reaching approximately 13 million listeners weekly. Black Radio continues to Tell It Like It Is.

Legendary Pioneers of Black Radio

by Gilbert A. Williams,

Praeger Publishers, 1998

ISBN: 0275958884.

Michael H. Burchett,

The Smithsonian

P.O. Box 23293

Washington, D.C. 20026-3293