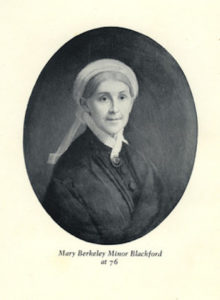

Mary Blackford

*Mary Minor Blackford was born on this date in 1802. She was a white-American abolitionist.

A native of Fredericksburg, VA, Mary Berkeley Minor was the daughter of John Minor and his second wife, Lucy Landon Carter Minor. She was the only daughter of eight children; her father died when she was thirteen. She received education for a girl of the era. On October 12, 1825, she married William Blackford, a prominent iron manufacturer's son and lawyer. They were deeply devout members of the Episcopal church. Despite all these accolades to their family and reputation, the family was never overly wealthy.

She grew up in the same environment as Jane Beale; both cherished family and community values but not the idea of Slavery. Jane believed that it was God's will for Blacks to be subservient to the white man; Mary saw differently, abhorred the institution, and sought to do her part in ending it. In 1829, she founded an auxiliary to the American Colonization Society.

"Within just a year, Mary and the auxiliary of women distributed tracts of land in Liberia to freed Blacks and recently freed slaves. They also raised over $500 (nothing to sneeze at in the 19th century) and recruited many notable members, such as former first lady Dolly Madison. The ladies worked hard to spread the word about their efforts and even published their annual report," Report of the Board of Managers,” in the Methodist Christian Sentinel. "Within just a year, Mary and the auxiliary of women distributed tracts of land in Liberia to freed Blacks and recently freed slaves. They also raised over $500 (nothing to sneeze at in the 19th century) and recruited many notable members, such as former first lady Dolly Madison. The ladies worked hard to spread the word about their efforts and even published their annual report, “Report of the Board of Managers,” in the Methodist Christian Sentinel.

In 1832, she wrote a journal documenting her strong opposition to Slavery and its evils in a book called "Notes Illustrative of the Wrongs of Slavery." In it, she described the horrors she witnessed as a citizen trapped in a slaveholding community like Fredericksburg. She was mainly influenced by living so close to a slave trader's jail while growing up. The grand jury also threatened her twice for teaching slaves to read the Bible. While she had the backing of her family and friends, including one of her brothers who went to Liberia as a missionary, her husband didn't share her beliefs. He approved of Colonization, but only to rid the country of the freed Blacks that he saw as a blemish upon the community.

The Blackford family owned a few slaves to help Mary with the daily housework. This was seen as a necessary evil. Mary gave birth to eight children in their first fifteen years of marriage (Lucy Landon, William Willis, Charles Minor, Benjamin Lewis, Launcelot Minor, Eugene, and Mary Isabella). With each child, her health and bodily vigor declined. Mary was stricken with severe back pain that debilitated her from her duties as a wife and her radical ambitions to reform society. The auxiliary received a facelift in 1834 when Mary became discouraged by the "unaccountable apathy. She renamed the auxiliary to the Ladies' Society of Fredericksburg and Falmouth to promote Female Education in Africa. It refocused from Colonization to the betterment of education for those Black girls and young women already in Liberia or those sent to Liberia from America by the auxiliary itself.

"She recruited Presbyterian missionaries to go to the country and give the girls the education she had in childhood. All of that changed in 1846. In the background, William Blackford had been bettering his career by editing and publishing a Whig newspaper. Between 1842 and 1845, he served as chargéd'affairess to New Granada in Bogotá. Her husband grew more sectional in his beliefs by the 1850s, and much of her family had sided with the Southern cause for states'’ rights and the preservation of Slavery. Her involvement in the American Colonization Society never stopped. Though the world she had known began to crumble around her, she never faltered in her faith that all people deserved freedom. In her journal, she wrote, "Think of what it is to be a slave! To be treated not as a man but as a personal chattel, a thing that may be bought or sold, to have no right to the fruits of your own labor, no right to your own wife and children… think of this, and all the nameless horrors that are concentrated in that one-word Slavery.” "She recruited Presbyterian missionaries to go to the country and give the girls the education she had in childhood. All of that changed in 1846. In the background, William Blackford had been bettering his career by editing and publishing a Whig newspaper. Between 1842 and 1845, he served as chargé d’affaires to New Granada in Bogotá. Her husband grew more sectional in his beliefs by the 1850s, and much of her family had sided with the Southern cause for states’ rights and the preservation of Slavery. Her involvement in the American Colonization Society never stopped. Though the world she had known began to crumble around her, she never faltered in her faith that all people deserved freedom. In her journal, she wrote, “Think of what it is to be a slave! To be treated not as a man but as a personal chattel, a thing that may be bought or sold, to have no right to the fruits of your own labor, no right to your own wife and children… think of this, and all the nameless horrors that are concentrated in that one-word Slavery.”

Her husband passed in April of 1864. Her children had grown by then, and she was left alone at 61. She moved to Alexandria to live with her son, Launcelot Minor Blackford, named after her compatriot brother, who became a missionary and spent her final days there. She died on September 15, 1896, and was buried in Spring Hill Cemetery in Lynchburg. Her legacy remains forever as a glowing example of what one person can do to change the lives of many and end the suffering of a people.