*Racial segregation in the United States of America is affirmed on November 19, 1862. These were (are) laws that excluded facilities and services to communities based on race.

The plight of Africans in the United States of America as chattel enslaved people was enforceable because of laws. Africans were brought to this country in the same category as a horse, a wheel barrel, or a cow, and they were labeled as property to be used by their owners for mainly agrarian profit. These enforceable regulations were enacted first by the Articles of Confederation. Living essentials such as housing, healthcare, education, religious rights, employment, and transportation were unattainable or monitored in bear rudiments to enslaved people. The American Civil War was not fought merely for the moral compass of President Lincoln or the (then) Republican Party. Southern planters in the Antebellum South used their slaves as people during election years to leverage political and financial influence. After emancipation and reconstruction, the racial values of the confederacy never actually left.

Integration in the United States on racial grounds is not the opposite of segregation. Segregation is mainly used for the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from whites. Still, it also references the alienation of other nonwhites from white and mainstream American communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other indicators such as bans against interracial marriage (enforced with anti-miscegenation laws) and the separation of roles within an institution. Notably, in the United States Armed Forces, up until 1948, black units were typically separated from white units but were still led by white officers. The one exception before that was the Tuskegee Airmen.

Racial segregation follows two forms.

Signposts indicated where Blacks could walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat legally. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) so long as "separate but equal" facilities were provided, a requirement rarely practiced. The segregation doctrine applied to public schools was overturned by the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In the following years, the Warren Court further ruled against racial segregation in several landmark cases, including Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964), which helped end the Jim Crow laws.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed De jure segregation In specific areas. The Warren Court barred segregation earlier in decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education, overturning school segregation in the United States.

· De facto segregation, or segregation "in fact," exists without the sanction of the law. De facto segregation continues today in residential and school segregation areas because of contemporary behavior and de jure segregation's historical legacy.

In an often-cited 1988 study, Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton compiled 20 existing segregation measures and reduced them to five dimensions of residential segregation. Dudley L. Poston and Michael Micklin argue that Massey and Denton "brought conceptual clarity to the theory of segregation measurement by identifying five dimensions ."African Americans are racially segregated because all five dimensions of segregation are applied to them within these inner cities across the U.S. These dimensions are evenness, clustering, exposure, centralization, and concentration.

1. Evenness is the difference between the percentage of a nonwhite group in a particular part of a city and the rest of the city.

2. Exposure is the likelihood that nonwhites and whites will meet one another.

3. Clustering is gathering different nonwhite groups into a single space; clustering often leads to one big ghetto and the formation of "hyper ghettoization."

4. Centralization measures the tendency of members of a nonwhite group to be in the middle of an urban area, often computed as a percentage of a nonwhite group living in the middle of a city (as opposed to the outlying areas).

5. Concentration is the dimension that relates to the actual amount of land a nonwhite lives on within its city. The higher the segregation within that area, the smaller the land a nonwhite group will control.

Sports.

Segregation in sports in the United States was also a major national issue. In 1900, just four years after the U.S. Supreme Court's separate but equal constitutional ruling, segregation was enforced in horse racing, a sport that had previously seen many Black jockeys win the Triple Crown and other major races. Widespread segregation also existed in bicycle and automobile racing. In 1890, segregation lessened for black track and field athletes after various universities and colleges in the northern states agreed to integrate their track and field teams.

Like track and field, soccer experienced little segregation early on. Many colleges and universities in the northern states allowed blacks to play on their football teams. Segregation was hardly enforced in boxing. In 1908, Jack Johnson became the first Black person to win the World Heavyweight Title. Johnson's personal life (i.e., his publicly acknowledged relationships with white women) made him unpopular among many whites worldwide. In 1937, when Joe Louis defeated German boxer Max Schmeling, the general American public embraced an African American as the World Heavyweight Champion.

In 1904, Charles Follis became the first Black person to play for a professional football team, the Shelby Blues, and professional football leagues agreed to allow only a limited number of teams to be integrated. In 1933, the NFL, now the only major football league in the United States, reversed its limited integration policy and wholly segregated the entire league. The NFL color barrier broke in 1946 when the Los Angeles Rams signed Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, and the Cleveland Browns hired Marion Motley and Bill Willis. Before the 1930s, basketball saw a great deal of discrimination as well. Blacks and whites played mostly in different leagues and usually could not play in interracial games. The popularity of the Harlem Globetrotters altered the American public's acceptance of blacks in basketball. By the end of the 1930s, many northern colleges and universities allowed blacks to play on their teams. In 1942, the color barrier for basketball was removed after Bill Jones and three other African American basketball players joined the Toledo Jim White Chevrolet NBL franchise, and five Harlem Globetrotters joined the Chicago Studebakers.

In 1947, the baseball color line was broken when Negro League baseball player Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and had a breakthrough season.

By the end of 1949, only fifteen states had no segregation laws. And only eighteen states had outlawed segregation in public accommodations. Of the remaining states, twenty still allowed school segregation, fourteen allowed segregation in public transportation, and 30 still enforced laws forbidding miscegenation.

NCAA Division I has two historically Black athletic conferences: the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference (founded in 1970) and the Southwestern Athletic Conference (founded in 1920). The Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (founded in 1912) and the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (founded in 1913) are part of NCAA Division II. In contrast, the Gulf Coast Athletic Conference (founded in 1981) is part of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics Division I.

In 1948, the National Association for Intercollegiate Basketball became the first national organization to open its intercollegiate postseason to black student-athletes. In 1953, it became the first collegiate association to invite historically black colleges and universities into its membership.

Golf was racially segregated until 1961. The Professional Golfers Association of America (PGA) had an article in its bylaws stating that it was "for members of the Caucasian race." Once the color restrictions were lifted, the United Golf Association Tour (UGA), comprised of Black players, ceased operations. They have a foundation to support black youth golfers.

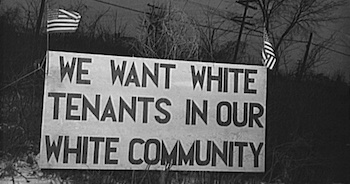

Residential.

Racial segregation is most pronounced in housing. Although in the U.S., people of different races may work together, they are still doubtful of living in integrated neighborhoods. This pattern differs only by a degree in other metropolitan areas. Residential segregation may be reinforced by the practice of "steering" by real estate agents. This occurs when a real estate agent makes assumptions about where their client might like to live based on the color of their skin. Housing discrimination may happen when landlords lie about the availability of housing based on the applicant's race or give different terms and conditions to the housing based on race, for example, requiring that black families pay a higher security deposit than white families.

Redlining has helped preserve segregated living patterns for blacks and whites in the United States through the racial composition of neighborhoods where the loan is sought and the applicant's race. This began with the National Housing Act of 1934. Lending institutions often treated black mortgage applicants differently when buying homes in white neighborhoods than in black communities in 1998.

These discriminatory practices are illegal. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibits housing discrimination based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, or disability. The Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity administers and enforces fair housing laws. Anyone who believes they have faced discrimination based on race can file a reasonable housing complaint.

Households were held back or limited to the money that could be made. Inequality was present in the workforce, leading to residential areas. This study provides this statistic: "The median household income of African Americans was 62 percent of non-Hispanic Whites ($27,910 vs. $44,504). The system forced Blacks to be in urban and poor areas while whites lived together to afford more expensive homes. These forced measures caused poverty levels to rise and depreciate Black home investment. Massey and Denton proposed that segregation is the fundamental cause of poverty among African Americans. This segregation has created the inner city Black urban ghettos that create poverty traps and keep blacks from being able to escape the underclass. It is sometimes claimed that these neighborhoods have institutionalized an inner-city black culture that is negatively stigmatized and purports the economic situation of the black community.

Historically, residential segregation split communities between the Black inner city and white suburbs. This is due to white flight, where whites often leave neighborhoods because of a black presence. There are more than just geographical consequences; as the money leaves and poverty grows, crime rates jump, and businesses leave and follow the money. This creates a job shortage in segregated neighborhoods and perpetuates the economic inequality in the inner city. With the wealth and businesses gone from inner-city areas, the tax base decreases, hurting education funding. Consequently, those who can afford to leave the area for better schools leave, diminishing the tax base for educational funding even more. Any business that is left or would consider opening doesn't want to invest in a place where nobody has any money but has poor Black people with little opportunity for employment or education.

Today, several whites are willing and can pay a premium to live in a predominantly white neighborhood. Equivalent housing in white areas commands a higher rent. By bidding up the price of accommodation, many white communities again effectively shut out blacks because Blacks are unwilling, or unable, to pay the premium to buy entry into white neighborhoods. While some scholars maintain that residential segregation has continued—some sociologists have termed it "hyper segregation" or "American Apartheid."

The U.S. Census Bureau has shown that residential segregation has declined since 1980. A 2012 study found that "credit markets enabled a substantial fraction of Hispanic families to live in neighborhoods with fewer black families, even though a substantial fraction of Black families were moving to more racially integrated areas. The net effect is that credit markets increased racial segregation." As of 2015, residential segregation had taken new forms in the United States, with Black majority minority suburbs such as Ferguson, Missouri, supplanting the historic model of Black inner cities and white suburbs.

Meanwhile, in locations such as Washington, D.C., gentrification developed new white neighborhoods in historically black inner cities. Segregation occurs through premium pricing by white people of housing in white areas and the exclusion of low-income housing rather than through rules that enforce segregation. Black segregation is most pronounced, Hispanic segregation less so, and Asian segregation the least.

Commerce.

Lila Ammons discusses the establishment of Black-owned banks from the 1880s to the 1990s. She describes five distinct periods illustrating the developmental process of establishing these banks.

In 1851, approximately 60 Black-owned banks were created, allowing blacks to access loans and other banking needs that white banks would not offer Blacks.

Only five banks were opened between 1929–1953. In comparison, they saw many black-owned banks closed, leaving these banks with an expected nine-year life span for their operations. With Blacks continuing to migrate toward northern urban areas during the great depression, they were challenged by high unemployment rates due to whites taking their jobs. The entire banking industry in the U.S. stagnated, and these smaller banks even more for having higher closure rates and lower loan repayment rates. The first groups of banks invested their profits back into the Black community. In contrast, banks established during this period invested mainly in mortgage loans, fraternal societies, and U.S. government bonds.

Between 1954 and 1969, approximately 20 more banks were established, and African Americans became active citizens. They participated in various social movements centered around economic equality, better housing, better jobs, and the desegregation of society. Through desegregation, these banks could no longer depend solely on the Black community for business and establish themselves on the open market. This meant paying their employees competitive wages and meeting society's needs instead of just the black community.

Urban deindustrialization occurred between 1970–1979, increasing the number of Black-owned banks to 35. However, this economic change allowed more banks to increase other impoverished African American communities in this period. Unemployment rates increased with the shift in the labor market from unskilled labor to government jobs. From 1980–1990, approximately 20 banks were established during this time, competing with other financial institutions that serve the economic necessities of people at a lower cost.

In the 21st century, Dan Immergluck writes that in 2003, small businesses in black neighborhoods still received fewer loans, even after accounting for business density, business size, industrial mix, neighborhood income, and the credit quality of local businesses. Gregory D. Squires wrote in 2003 that race has long affected and continues to affect the policies and practices of the insurance industry. Workers living in American inner cities have a more challenging time finding jobs than suburban workers, a factor that disproportionately affects Black workers.

Rich Benjamin's book Searching for Whitopia: An Improbable Journey to the Heart of White America reveals the state of residential, educational, and social segregation. In analyzing racial and class segregation, the book documents the migration of white Americans from urban centers to small-town, exurban, and rural communities. Throughout the 20th century, racial discrimination was deliberate. Today, racial segregation and division result from policies and institutions no longer explicitly designed to discriminate. Yet the outcomes of those policies and beliefs have negative racial impacts, namely segregation.

The pattern of hypersegregation began in the early 20th century. Blacks who moved to large cities were often forced into the inner city for industrial jobs. In the case of white flights, this influx of new black residents caused many white residents to move to the suburbs. As the industry began to move out of the inner-city, black residents lost the stable jobs that had brought them to the area. Many were unable to leave the inner city and became increasingly poor. This created the inner-city ghettos that make up the core of hypersegregation. Though the law banned discrimination in housing, housing patterns established earlier saw the perpetuation of hyper-segregation.

Data from the 2000 census showed that 29 metropolitan areas displayed Black-white hypersegregation. Two regions, Los Angeles and New York City, displayed Hispanic-white segregation, too. No metro area displayed hypersegregation for Asians or Native Americans. In 2017, the Metropolitan Planning Council in Chicago and the Urban Institute, a think-tank located in Washington, DC, released a study estimating that racial and economic segregation costs the United States billions of dollars annually. Statistics (1990–2010) from at least 100 urban hubs were analyzed. This study reported that segregation affecting Blacks was associated with higher rates of homicide.

Scientific racism.

Scientific racism is the belief that first-hand evidence exists to support or justify racism, racial inferiority, or racial superiority. Historically, scientific racism received credence throughout the scientific community, but it is no longer considered scientific. They divide humans into biologically distinct groups and credit specific physical and mental traits to them by constructing and applying corresponding explanatory models, i.e., racial theories. Modern scientific consensus rejects this view as being irreconcilable with current genetic research. Scientific racism is generally used in modern ideas, such as The Bell Curve (1994). Publications such as the Mankind Quarterly, founded explicitly as a "race-conscious" journal, are generally regarded as platforms of scientific racism because they publish extremist interpretations of human evolution, intelligence, and race.

Transportation.

Local bus companies practiced segregation in city buses. This was challenged in New Orleans, leading to the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott, and by Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat to a white passenger, leading to the Montgomery bus boycott. A federal court suit in Alabama, Browder v. Gayle (1956), was successful at the district court level, which ruled Alabama's bus segregation laws illegal. It was upheld at the Supreme Court level. In 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality members and some Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee members traveled as a mixed-race group, Freedom Riders, on Greyhound buses from Washington, D.C., headed toward New Orleans. In several states, travelers were subject to violence. In Anniston, Alabama, the Ku Klux Klan attacked the buses, setting one bus on fire. After U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy resisted acting and urged restraint by the riders, Kennedy relented. He urged the Interstate Commerce Commission to issue an order directing buses,

Education.

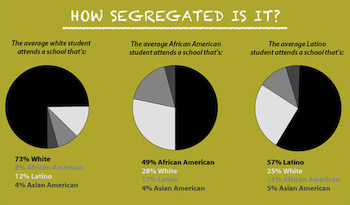

In the United States, funding for public education relies greatly on local property taxes, and tax revenues may vary between neighborhoods and school districts. This variance in property tax revenues leads to inequality in education. This inequality shows up in the form of available school financial resources. This provides educational opportunities, facilities, and programs to students. For every student enrolled, the average nonwhite school district receives $2,226 less than a white school district. Affluence and poverty have become highly segregated and concentrated concerning race and location.

Residential segregation and poverty concentration are most markedly seen in the comparison between urban and suburban populations in which suburbs consist of majority white populations and inner cities consist of majority nonwhite populations. According to Barnhouse-Walters (2001), the concentration of poor minority populations in inner cities and the concentration of affluent white people in the suburbs "is the main mechanism by which racial inequality in educational resources is reproduced." In August 2020, the US Justice Department argued that Yale University discriminated against Asian candidates based on race, a charge the university denied.

Health.

Hypersegregation impacts the health of the residents of specific areas. Poorer inner cities often lack health care compared to outside sites. That many inner cities are so isolated from other parts of society contributes to the poor health usually found in their residents. The overcrowded living conditions in the inner-city caused by hypersegregation means that the spread of infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, occurs much more frequently. This is known as "epidemic injustice" because racial groups confined in a specific area are affected much more often than those living outside the area. Poor inner-city residents also must contend with other factors that negatively impact their health. Research has proven that hypersegregated blacks are far more likely to be exposed to dangerous levels of air and water toxins in every major American city. Daily exposure to these pollutants means that blacks in these areas are at greater disease risk. The Environmental Justice movement developed in the United States throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The term describes environmental injustice within a racialized context in practice and policy.

Crime.

One area where hyper-segregation seems to have the most significant effect is the violence experienced by residents. The number of violent crimes in the U.S. generally has fallen. The number of murders in the U.S. fell by 9% from the 1980s to the 1990s. Despite this, the crime rates in the American hyper-segregated inner cities continued to rise. As of 1993, young Black men are eleven times more likely to be shot to death and nine times more likely to be murdered than whites. Poverty, high unemployment, and broken families, all factors more prevalent in hypersegregated inner cities, contribute significantly to the unequal levels of violence experienced by African Americans. Research has proven that the more segregated the surrounding white suburban ring is, the rate of violent crime in the inner city will rise, but corruption in the outer area will drop.

Poverty.

One study finds that an area's residential racial segregation increases metropolitan rates of Black poverty and overall Black-white income disparities while decreasing rates of white poverty and inequality within the white population.

Caste System

Scholars, including Isabel Wilkerson, have described the pervasive practice of racial segregation in America as an aspect of a caste system proper to the United States. In her 2020 book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, Wilkerson described the system of racial segregation and discrimination in the United States as one example of a caste system by comparing it to the caste systems of India and Nazi Germany. In her view, the three systems all exhibit the defining features of caste: divine or natural justification for the system, heritability of caste, endogamy, belief in purity, occupational hierarchy, dehumanization and stigmatization of lower castes, terror, and cruelty as methods of enforcement and control, and the belief in the superiority of the dominant caste.

In 2024, racial microaggressions have become acceptable verbal opinions in America. Some examples are Theme: Color Blindness

Statements that indicate that a white person does not want to acknowledge race.

Microaggression: “When I look at you, I don’t see color,” or “America is a melting pot,” “There is only one race, the human race.”

Message: Denying a person of color’s racial/ethnic experiences. Assimilate/acculturate to the dominant culture. Denying the individual as a racial /cultural being.