*On this date in 1993, the United States Supreme Court ruled on Shaw v. Reno. In this case, the Supreme Court's position was a troubled compromise on the issue of race and political redistricting.

The ruling did not provide clear rules for applying its appearance-based test for violations of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. On the issue of compassionate, race-conscious state actions that may propose increasing minority involvement in the political process, the Court appears to suggest that some benign discrimination is acceptable. Still, it must not be too obvious, as it exposes the purposes of the irregular districting. The Court accepted race as one factor in decision-making, but not the lone factor. In a democratic society, voting enables electors to choose their representatives. Argued on April 20, 1993, the appeal came from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina.

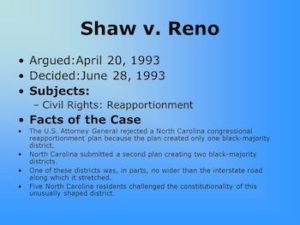

To comply with 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 - which prohibits a covered jurisdiction from implementing changes in a "standard, practice, or procedure concerning voting" without federal authorization - North Carolina submitted to the Attorney General a congressional reapportionment plan with one majority-Black district. The Attorney General objected to the plan because a second district could have been created to give effect to minority voting strength in the State's south-central to southeastern region. The State's revised plan contained a second majority-Black district in the north-central region.

The new district stretches approximately 160 miles along Interstate 85 and is no wider than the highway for much of its length. Appellants, five North Carolina residents, filed this action against appellee state and federal officials, claiming that the State had created an unconstitutional racial gerrymander in violation of, among other things, the Fourteenth Amendment. They alleged that the two districts concentrated a majority of Black voters arbitrarily without regard to considerations such as compactness, contiguousness, geographical boundaries, or political subdivisions to create congressional districts along racial lines and to ensure the election of two Black representatives.

Argued on April 20, 2001, the three-judge District Court held that it lacked subject matter jurisdiction over the federal appellees. It also dismissed the complaint against the state appellees, finding, among other things, that, under United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (UJO), appellants had failed to state an equal protection claim. This was because favoring minority voters was not discriminatory in the constitutional sense, and the plan did not lead to the proportional underrepresentation of white voters statewide. [509 U.S. 630, 2].

Yes, the Shaw case fought voter suppression. The Court held that although North Carolina's reapportionment plan was racially neutral, the resulting district shape was bizarre enough to suggest that it constituted an effort to separate voters into different districts based on race. The unusual district, perhaps created by noble intentions, seemed to exceed what was reasonably necessary to avoid racial imbalances. After concluding that the residents' claim did give rise to an equal protection challenge, the Court remanded, adding that in the absence of contradictory evidence, the District Court would have to decide whether or not some compelling governmental interest justified North Carolina's plan.