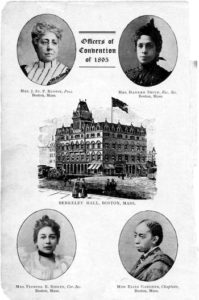

Conference Program

*On this date in 1895, the First National Conference of the Colored Women of America was held. Representatives of 42 Black women's clubs from 14 states—including the Colored Women's League of Washington, the Women's Loyal Union of New York, and the Ida B. Wells Club of Chicago gathered in Berkeley Hall with Josephine Ruffin presiding.

They convened at the hall for three days, with an extra session on August 1 at the Charles Street Church. According to the New York Times, it was "the first movement of the kind ever attempted". Background. In 1892, Boston activist Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin founded the Woman's Era Club, an advocacy group for black women, with the help of her daughter, Florida Ruffin Ridley, and educator Maria Louise Baldwin. It was the first Black women's club in Boston. Its members, prominent Black women from the Boston area, devoted their efforts to education, women's suffrage, and race-related issues such as anti-lynching reform.

Its slogan was "Help to make the world better." The club's newspaper was the Woman's Era, an illustrated monthly publication. In the early 1890s, the response was overwhelmingly positive when the Woman's Era polled readers to see if there was a need for a national organization of black clubwomen. In 1895, an obscure Missouri journalist named John Jacks sent a letter to the secretary of the British Anti-Slavery Society, Florence Belgarnie. In the letter, Jacks criticized the anti-lynching work of Ida B. Wells and wrote that black women had "no sense of virtue" and were "altogether without character." Outraged, Belgarnie sent the letter to Ruffin, who distributed the letter to various women's clubs in her call to organize. Soon after, Ruffin organized a national conference in Boston and asked clubs to send delegates.

The first day was devoted to organizing, and the second and third to "vital questions concerning their moral, mental, physical and financial growth and well-being." In the call, Ruffin explained the choice of venue: Boston has been selected as a meeting place because it has seemed to be the general opinion that here, and here only, can be found the atmosphere which would best interpret and represent us, our position, our needs, and our aims. In her opening address, Ruffin explained: Our woman's movement is woman's movement in that it is led and directed by women for the good of women and men, for the benefit of all humanity, which is more than any one branch or section of it. We want, we ask, the active interest of our men, and we are not drawing the color line; we are women, American women, as intensely interested in all that pertains to us as such as all other American women.

Several notable speakers addressed the group. Margaret Murray Washington gave an influential speech titled "Individual Work for Moral Elevation." African American women, she said, were divided into two classes: those who "had the opportunity to improve and develop mentally, physically, morally, spiritually and financially" and those who had been deprived of that opportunity by slavery. She urged members of the former class to do all they could to uplift and inspire the latter, reasoning that individual success was not enough; only by "lifting as we climb" was it possible for the race to progress.

Ella L. Smith, the first Black woman to receive an M.A. degree from Wellesley College, spoke about the need for higher education. Scholar Anna J. Cooper talked about the need to organize. In "The Value of Race Literature," author and former slave Victoria Earle Matthews stressed the importance of collecting literature by and about African Americans. Agnes Jones Adams gave a speech titled "Social Purity," in which she asserted that being white was not a "criterion for being American."

Civil rights leader T. Thomas Fortune and social reformers Henry B. Blackwell and William Lloyd Garrison spoke about political equality. Helen Appo Cook, president of the National League of Colored Women, read a paper on "The Ideal National Union." Alexander Crummell, Anna Sprague (the daughter of Frederick Douglass), and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells also spoke. Other club women gave speeches on justice, temperance, and the need for industrial training.

As the convention's chaplain, Eliza Ann Gardner of Boston gave the opening benediction. Although it was not unheard of for Christian women to preach in those days, it was unusual for a woman to be given the title of chaplain. Alice T. Miller of Boston read a poem, and singers Moses Hamilton Hodges and Arianna Sparrow performed solo.