*The Treaty of Payne's Landing was signed on this date in 1832. This agreement was between the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indian tribe in the Territory of Florida before it acquired statehood.

By the Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823, the Seminoles had relinquished all claims to land in the Florida Territory in return for a reservation in the center of the Florida peninsula and certain payments, supplies, and services to be provided by the U.S. government, guaranteed for twenty years. After the election of Andrew Jackson as President of the United States in 1828, the movement to transfer all Native Americans in the United States west of the Mississippi River grew. In 1830, the United States Congress passed the Indian Removal Act.

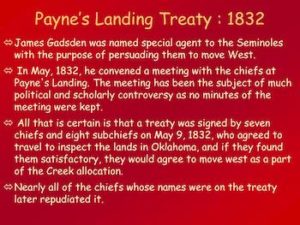

The United States Department of War appointed James Gadsden to negotiate a new treaty with them. The Seminoles on the reservation were called to a meeting at Payne's Landing on the Oklawaha River. The negotiations were conducted in obscurity, if not secrecy. No minutes were taken, nor were any detailed accounts of the talks published. This was to lead to trouble later. The U.S. government wanted the Seminoles to move to the Creek Reservation in what was then part of the Arkansas Territory (which later became part of the Indian Territory), to become part of the Creek Nation, and to return all runaway slaves to their lawful owners.

None of these demands were agreeable to the Seminoles. The climate at the Creek Reservation was harsher than in Florida, and they did not consider themselves part of the Creeks. Finally, runaway slaves, while often held as slaves by the Seminoles (under much milder conditions than with whites), were well integrated into the bands, often intermarrying and rising to positions of influence and leadership. The treaty had given the Seminoles three years to move, starting in 1832, and expected the Seminoles to move in 1835. A new Seminole agent, Wiley Thompson, was appointed in 1834, and the task of persuading the Seminoles to move fell to him. He called the chiefs together at Fort King, and the Seminoles informed Thompson that they had no intention of moving and did not feel bound by the Treaty of Payne's Landing.

Thompson then requested reinforcements for Fort King and Fort Brooke. Brigadier General Duncan L. Clinch, United States Army commander for Florida, warned Washington that the Seminoles did not intend to move and that more troops would be needed to force them. In March 1835, Thompson called the chiefs together to read Andrew Jackson's letter. In his letter, Jackson said, "Should you ... refuse to move, I have directed the Commanding officer to remove you by force." Eventually, eight of the chiefs agreed to move west but asked to delay the move until the end of the year, and Thompson and Clinch agreed. Five of the most important Seminole chiefs, including Micanopy of the Alachua Seminoles, had not agreed to the move. Thompson declared that those chiefs were removed from their positions in retaliation.

As relations with the Seminoles deteriorated, Thompson forbade the sale of guns and ammunition to the Seminoles. Osceola, a young warrior beginning to be noticed by the whites, was distressed by the ban, feeling that it equated Seminoles with slaves, and said, "The white man shall not make me black. I will make the white man red with blood and then blacken him in the sun and rain ... and the buzzard lives upon his flesh." The situation grew worse. In August 1835, Private Kinsley Dalton (for whom Dalton, Georgia, is named) was killed by Seminoles as he carried the mail from Fort Brooke to Fort King. In November, Chief Charley Emathla, wanting no part of a war, led his people towards Fort Brooke, where they were to board ships to go west. This was considered a betrayal by other Seminoles. Osceola met Emathla on the trail and killed him. The Second Seminole War was beginning.