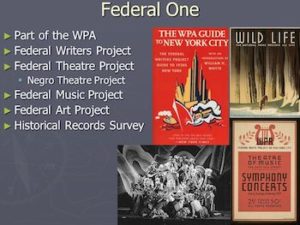

On this date, we celebrate the Federal Writers Project (FWP). FWP was an extension of the New Deal’s Works Project Administration (WPA) that employed about 4,500 American writers between 1935 and 1939, 106 of whom were African Americans.

The American Guide Series, a collection of state guidebooks describing the distinctive folkways and histories of the rural and urban regions of the United States, dictated most of the writers' employment. Many prominent Black writers took part in the FWP. The Illinois project hired Margaret Walker, Richard Wright, Willard Motley, Frank Yerby, William Attaway, Fenton Johnson, Arna Bontemps, and Katherine Dunham.

The New York project hired Wright, Claude McKay, Ralph Ellison, Tom Poston, Charles Cunberbatch, Henry Lee Moon, Roi Ottley, Helen Boardman, Ellen Tarry, and Waring Cuney. Zora Neale Hurston briefly directed the Florida project, and the Tennessee State Guild was part of Charles S. Johnson's contribution. Quite a bit of the material never saw publication because the funds were cut in 1939, and various projects reverted to individual states. Yet FWP writers on FWP-based research generated several vital studies of Black culture. Urban studies include McKay, Harlem: Negro Metropolis, 1940; Wright, Twelve Million Black Voices, 1941; Ottley and William Weatherby, New World A-Comin’: Inside Black America, 1943; St. Clair Drake and Horace Clayton, Negro Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, 1945; Moon, Balance of Power: The Negro Vote 1948;, Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto 1965; Bontempts and Jack Conroy, Anyplace But Here, 1966, and Ottley, The Negro in New York: An Informal History, 1967.

Rural FWP studies were taken from a massive interviewing project of over 2,000 ex-slaves from 18 states. They include: the North Carolina project’s These Are Our Lives, 1939; the Savannah project’s Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies among the Georgia Coastal Negroes, 1940; Roscoe Lewis, The Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery, 1945; George P. Rawick’s 19-volume The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography 1972 (subsequently supplemented in 1977 and 1979 by 22 additional volumes; and Charles L. Perdue, Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-Slaves, 1976. Resources put together in the slave narrative collection, while defective, continue to be used in studies of American slavery.

Sterling A. Brown, the FWP’s national editor of Negro affairs, had a goal of Brown’s goal of eliminating “racial bias,” but ran into resistance from several state project heads who refused to hire Black interviewers. Thus, some historians of slavery insist that because most of the FWP interviewers were white, the former slaves engaged in self-censorship, leading to a distorted view of plantation life and a homogenized or fear-based commentary. Many African American writers wrote and published their material through the FWP.

The FWP experience not only provided these writers with financial support but also notably shaped the content and perspective of the works. It offered a means to travel to get to the root of the environments and subject matter and to interview characters in depth. Though the House Un-American Activities Committee claimed the FWP was “doing more to spread Communist propaganda than the Communist Party itself,” this was not true; instead, the FWP and the work performed by African American writers within it showed an intense approach to capturing America’s diverse traditions.

Encyclopedia of African American Culture and History

Volume 1, ISBN #0-02-897345-3, Pg 175

Jack Salzman, David Lionel Smith, Cornel West