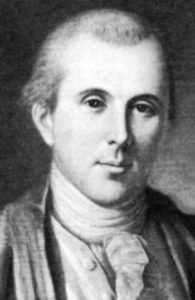

Benjamin Rush

*Benjamin Rush was born on this date in 1746. He was a white-American abolitionist, physician, and diplomat. His interpretation of white privilege of race has raised many ethical questions.

The fourth of John and Susanna (Hall) Rush's seven children, he was raised and spent most of his life in Philadelphia. His mother, a Presbyterian, first supervised his religious education at home. After his father's death, he regularly attended the Second Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. Gilbert Tennent, its minister and leader in the Great Awakening, greatly influenced the young Rush, who then swept the northeast. Exposure to Calvinist teachings continued during his student years at West Nottingham Academy in Maryland and at the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). He accepted these doctrines and later wrote, "without any affection for them."

After earning an A.B. in 1760 from the College of New Jersey From 1761-66, Rush studied medicine under Dr. John Redman in Philadelphia. On Redman's advice, he continued his studies at the University of Edinburgh, receiving an M.D. degree in 1768. He further trained at St. Thomas's Hospital in London, 1768-69. Returning to America, he joined the College of Philadelphia faculty as a chemistry professor. In 1789, he became a professor of the theory and practice of medicine. When the college became part of the University of Pennsylvania, he was appointed chair of the Institutes of Medicine and Clinical Practice in 1791 and chair of Theory and Practice of Medicine in 1796. He was immensely popular with his students; his lectures drew large crowds. His fame drew many students to Philadelphia to study medicine. In 1776, he married Julia Stockton; the couple had 13 children.

As an abolitionist, in 1787, he joined the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society, not only as an advocate but also as an author of its new constitution and as secretary and later president. He maintained close contacts with Philadelphia’s Black community, including helping found the city’s Bethel AME church. The narrative of Rush’s views on Blacks, slavery, and abolitionism is complicated by other facts. Rush bought and owned a child slave, William Grubber until he freed him for compensation in 1794. The question and answers of conflicted values about voicing strident views against slavery while owning another human being show little comment in his writings. Rush also mixed his views on race with his interests in physical science and firm religious beliefs.

Eager to prove that all human beings “descended from one pair,” Adam and Eve, he came to think that the disease of leprosy caused the blackness in skin color. A cure, therefore, would change Africans’ skin color “back” to white, thereby allowing Rush to support his Christian creationism, counter those who argued that Blacks were naturally disposed to enslavement, and support their future assimilation as full citizens. As he argued, “all of the claims of superiority of the whites over the blacks, on account of their skin color, are founded alike in ignorance and inhumanity.” Rush based this claim partly on the experimentation of another scientist who applied muriatic acid, a harsh corrosive, to the skin and hair of a Black man. Rush made no mention of the glaring moral problems with that practice.

A signer of the American Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Rush was the most celebrated American physician and the leading social reformer of his time. He was a close friend of both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson and corresponded with many of the white figures of the revolutionary generation. Rush's strong belief in universal salvation helped to promote the acceptance of Universalism during its formative period in America. Benjamin Rush died of Typhoid Fever on April 19, 1813; he is buried in the Crist Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia.