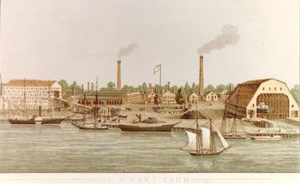

The Washington Shipyard

(Harpers Lithograph 1862)

*Black history and the American labor movement are affirmed on this date in 1835. This article coincides with the Washington Navy Yard labor strike of 1835, the first strike of federal civilian employees. The strike ended on August 15, 1835.

In the early nineteenth century, blacks played a dominant role in the caulking trade, and this is documentation of a strike by black caulkers. The strike also supported the movement, advocating a ten-hour workday and redressing grievances such as those imposed by lunch-hour regulations. The strike failed in its objectives for two reasons: the Secretary of the Navy refused to change the shipyard working hours, and the loss of public support due to the involvement of large numbers of mechanics and laborers in the race riot popularly known as the Snow Riot. Caulking was necessary in shipbuilding, for a ship was not fit for service unless caulked to prevent leaking.

At the end of the American Civil War, ex-slaves had to adapt to a new labor system. The National Archives contains millions of documents concerning this transition. Fortunately, researchers can benefit from Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, a multivolume documentary editing project. The Freedom volumes are twenty-five National Archives record groups, including Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands; Records of Civil War Special Agencies of the Treasury Department; Records of the United States General Accounting Office; the Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917; the Records of the Office of the Paymaster General; and Records of District Courts of the United States. Other record groups are less obvious sources of information.

The General Records of the Department of State and the General Records of the Department of Justice contain documentation of the black dock workers in Pensacola, Florida. In the winter of 1873-1874, the latter organized a Workingman’s Association and successfully defended their jobs against Canadian dockers brought in by dock owners. The formation of American trade unions increased during the early Reconstruction era. Black and white workers shared a heightened interest in trade union organizations. Still, because trade unions organized by white workers generally excluded blacks, black workers began to organize independently. In December 1869, 214 delegates attended the Colored National Labor Union convention in Washington, D.C. This union was a counterpart to the white National Labor Union.

The assembly sent a petition to Congress requesting direct intervention in alleviating the “condition of the colored workers of the Southern States” by subdividing the public lands of the South into forty-acre farms and providing low-interest loans to black farmers. In January 1871, the Colored National Labor Convention again petitioned Congress, sending a “Memorial of the Committee of the National Labor Convention for Appointment of a Commission to Inquire into Conditions of Affairs in the Southern States.” Congress showed little interest in either petition. Five years later, the disputed presidential election of 1876 led to the Compromise of 1877, the selection of Rutherford B. Hayes as President of the United States, the end of Reconstruction, and the beginnings of “Redeemer Rule” and “Jim Crow.”

When the Supreme Court handed down the Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896, giving official recognition to the “separate but equal” doctrine, the official relegation of Blacks to second-class status was complete. A review of the records and reports of the Bureau of the Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. House of Representatives, and the U.S. Senate revealed volumes of information concerning the lives of African Americans during this period. A small sampling of these reports and publications includes the U.S. Bureau of the Census, Bulletin No. 8, Negroes in the United States (1905); the U.S. Bureau of Labor, Sixteenth Annual Report of the Commissioner (1901); and the U.S. Senate Committee on Education and Labor, Forty-ninth Congress, second session, Testimony Before the Committee to Investigate the Relations Between Capital and Labor (1885). W.E.B. Du Bois provided some statistical data on black labor to the Bureau of Labor and wrote reports for the Census Bureau.

The decline of African Americans vis à vis organized labor included the railroad industry. During the Great Strike of 1877, for instance, rallies and marches in St. Louis, Louisville, and other cities brought together white and black workers to support the common rights of workingmen. By 1894, Eugene Debs, leader of the American Railway Union, had been on a strike against the Pullman Company, but he could not convince his union members to accept black railroaders. Blacks, in turn, served as strikebreakers for the Pullman Company and for the owners of Chicago meatpacking companies against whom stockyard workers struck in sympathy with the Pullman Company employees. Also, during the 1890s, Consolidated Coal Company opened mines in the Midwest. Buxton, Iowa, employed Black and white Welsh laborers who were not represented by a union.

In 1909, white employees of the Georgia Railroad, represented by the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, walked off their jobs, demanding that higher-paid whites replace lower-paid black firefighters. A Federal Board of Arbitration, appointed under the Erdman Act of 1898, ruled two to one against the Brotherhood, stating that blacks had to be paid equal pay for equal work, eliminating the financial advantage of hiring blacks. Erdman docket file 20, the Georgia Railroad Co. v. The Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, is found in the Records of the National Mediation Board.

The National Mediation Board was created by the amended Railway Act of June 21, 1934, to mediate railroad and airline disputes. The board inherited the functions of various boards and panels designed to mediate railroad disputes. The records of the National Mediation Board and its predecessors date from 1934 to 1965. The creation of federal railroad arbitration boards marked the beginning of federal efforts to stabilize and rationalize labor relations. Black women welders also began filling jobs in welding to support the United States during World War II. Also, in the 1930s, Charlotte Adelmond, a black woman from Trinidad, and Dollie Lowther Robinson from South Carolina, organized laundry workers through Local 810, the union in New York City.

On March 4, 1913, the U.S. Department of Labor cabinet authorized the Secretary of Labor, William Wilson, to mediate or appoint conciliation commissioners in labor disputes. This conciliation function by the United States Conciliation Service became the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service under the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947. The Labor-Management Act of 1947 (Taft-Hartley) outlawed wildcat strikes, mass picketing, and secondary boycotts—tactics used to win union recognition. The act gave managers the right to force employees to attend anti-union meetings and approved laws in 11 states that allowed employees to opt out of paying union dues.

In the meantime, the 20th-century American Civil Rights movement gained momentum. A. Philip Randolph and other leaders pressured President Truman to desegregate the armed forces, and he did so in 1948. In 1954, the Supreme Court declared “separate but equal” unconstitutional. Local activists began pushing for equal treatment in the Deep South. Rosa Parks' refusal to give up her seat to a white man set off a two-year bus boycott in Montgomery, AL. It nearly bankrupted public transportation until it finally agreed to equal seating. When the AFL and CIO merged in 1955, hundreds of thousands of black trade unionists became part of an integrated labor movement. George Meany became its first president, and A. Philip Randolph became its first vice president. The Sleeping Car Porters and the UAW were among the first supporters of the new Southern Christian Leadership Conference. They also supported the Woolworth counter sit-ins by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Freedom Rides organized by the Congress of Racial Equality in the summer of 1961. Randolph and other black trade unionists helped plan, organize, and fund King’s 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

In their commitments and vision, these Black trade unionists linked the priorities and interests of the labor movement with demands for racial equality. John Kennedy recognized that labor had been crucial to winning the presidency in 1960 and created a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) that would be true to its original mission. His NLRB restricted anti-union propaganda at the workplace, allowed picketing, increased the penalties for violating labor law, and banned employer lockouts as an “unfair labor practice.” Most importantly, it ruled that if a majority of workers signed a card saying they wanted to join a union, the union would be recognized. Kennedy also established collective bargaining rights for federal employees in 1962. Although limited in scope, it spurred state and municipal public-sector union organizing just as anti-discrimination rules opened public-sector jobs to African Americans and Great Society programs expanded public-sector jobs. In 1960, only two percent of state and local public employees had the right to bargain collectively; by 1990, more than two-thirds did. The rapid expansion of public-sector unions has been a boon to the labor movement and the growth of the black middle class.

After Kennedy’s assassination, Lyndon Johnson won the 1964 election with the most significant vote advantage since 1824 and a veto-proof majority in both chambers of Congress. He did not waste his opportunity. His administration was responsible for

· Outlawing employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

· Desegregating public accommodations.

· prohibiting poll taxes and other tools Southern states used to restrict voting.

· requiring federal contractors to “affirmatively act” to hire more African Americans.

· prohibiting discrimination in rental housing and mortgages.

· Establishing Medicare for the elderly, Medicaid for the poor, food stamps, Head Start, the Job Corps, and federal aid to poor primary and secondary schools and farm families.

· Investing in public universities, urban mass transit, job training, urban renewal programs, and housing subsidies.

· abolishing national-origin quotas in immigration law; and

· establishing clean air and water quality standards, safety standards on cars, fair labeling, food safety standards, and consumer lending regulations.

For labor, President Johnson extended labor standards to cover nine million more workers, improved Davis-Bacon, and increased the federal minimum wage. However, labor density did not grow. The 1960s were a time of conflict and division. Many whites were uncomfortable with the anti-war protests or the pace of racial change. And many blacks in the North were not, either. They celebrated the end of de jure segregation in the South. Still, they were increasingly frustrated with the de facto housing and school segregation, job discrimination, and police brutality in their own lives.

Union Firemen, 1944

With the rise of new social movements, anti-war activism, Black Liberation, Black Nationalism, and the women’s movement, the country was divided, and still reeling from President Kennedy’s assassination. Many suspected government involvement when Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965. Later that year, a riot in Watts broke out after an incident with the police; 34 died, most of them black. During the “long hot summer” of 1967, more than 159 urban disturbances occurred in black neighborhoods, most related to violent encounters between white police and black residents of inner cities with high unemployment rates. The worst riots occurred in Cleveland, Detroit, and Newark, NJ.

Over 100 people died, and thousands were injured—most killed or wounded were black. Dr. King recognized that the end of legal segregation was a battle in the struggle for full equality and that good jobs were the key to black advancement. He believed in unions as a mechanism for higher wages and economic opportunity. He was speaking in support of the “I Am a Man” strike of Black Memphis sanitation workers—AFSCME members—when King was assassinated in 1968.

In the immediate hours after Dr. King’s killing, rioting erupted in 130 cities. Dozens of people died, but the 65,000 federal and National Guard troops called out to quell the violence and told them not to shoot looters, so the death toll was less than it might have been. Two months later, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. In August, the nation watched four days of fighting between protesters and police at the Democratic convention in Chicago; more than 1,000 were injured, and 600 were arrested. In October, 100,000 white and black students marched against the war in Vietnam. Some protesters and police tussled, and more than 650 people were arrested.

In the Kennedy-Johnson years, labor and civil rights leaders fought for racial justice, labor rights, public investments in infrastructure and training, better retirement security, better access to college and health care, and anti-poverty initiatives. Both black and white poverty rates were cut by half (from 55 percent to 27 percent and from 20 percent to 10 percent, respectively), but union density continued to fall. The nation went to the polls in 1968, disturbed and divided. George Wallace, a white segregationist, ran as a third-party candidate and won almost 10 million votes (12 percent) and five states. Only 500,000 votes divided Nixon from Humphrey, but Nixon won an electoral landslide and declared a mandate.

Starting with Richard Nixon and extending to Donald Trump, white-American conservative politicians wrote a new playbook: activate racial fears while lifting white people as “the silent majority,” “real” Americans, “people who play by the rules.” While publicly displaying empathy for “the middle class” or “working people,” instruct your political appointees to dismantle labor protections, restrict union activities, and undermine civil rights protections. Nixon’s campaign, which called for “law and order,” was an unsubtle promise to crack down on black demands for full equality. He spent his first two years increasing federal funds to police departments for anti-riot equipment and cutting funds for small businesses, education, and job training. By 1971, Nixon’s NLRB had undone all progressive labor reforms established under Kennedy’s NLRB.

Jimmy Carter won 48 percent of the white vote and 62 percent of the union vote in 1976. Still, instead of recasting the NLRB or reforming Taft-Hartley, he deregulated the highly unionized trucking, airlines, and communications industries. By 1980, private-sector union density had dropped to 20 percent. When Ronald Reagan ran a campaign openly promoting racial stereotypes in 1980, he won 56 percent of the white vote but only 45 percent of the union household vote. In 1981, he fired 11,000 air traffic controllers—who had endorsed him—and banned them for life from federal employment.

Reagan’s NLRB ruled employers could hire permanent replacement workers and created a long list of prohibited labor practices. He cut anti-poverty programs, gutted the Civil Rights Commission, and appointed conservative Supreme Court judges. In 1984, 66 percent of whites voted to reelect him, but only 46 percent of union households did. George H.W. Bush opened immigration and negotiated a North American Free Trade Agreement without labor protections.

Bill Clinton won the presidency in 1992 with only 39 percent of the white vote (thanks to third-party candidate Ross Perot), but he won 55 percent of union households. Clinton won 44 percent of the white vote and 60 percent of union households in 1996. His NLRB allowed teaching assistants and temp workers to unionize and protected union rights when businesses merged. But he ended the guarantee of income assistance for low-income families, passed stiff new mandatory drug laws responsible for the mass incarceration crisis we now face, implemented NAFTA, and deregulated the financial industry.

George W. Bush won 55 percent of the white vote and just 37 percent of union households in 2000. He appointed a union-busting lawyer to chair the NLRB and an anti-labor secretary of labor. In his 2004 reelection, he won 58 percent of the white vote and 40 percent of the union vote. The Bush response to the Katrina disaster in New Orleans demonstrated what many African Americans felt his attitude was on racial justice: black lives in New Orleans did not matter. Only 39 percent of whites voted for Barack Obama in 2008, but 59 percent of union households did—and more white union members voted for Obama in 2008 than for Gore or Kerry. The result represented a significant show of solidarity by union members, repeated in his 2012 reelection.

At that time, labor had the most pro-labor administration since Kennedy-Johnson. Although unable to pass the Employee Free Choice Act, other important legislation was passed: The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, the Affordable Care Act (which improved coverage but needs improvements), the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, and financial reform. The Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) bargained with air traffic controllers, and 40,000 TSA airport screeners won bargaining rights. The Obama Administration encouraged insourcing federal work and gave new funds to worker protection agencies to bolster enforcement. Obama’s NLRB staffed experienced labor lawyers committed to its mission who were able to streamline the election process, reduce opportunities for employer delay, and adopt a new standard for joint-employer status. With the election of Donald Trump, all these advances were at risk.

In the past 100 years, labor turned its voting power into a union-supporting political environment in just three administrations—Roosevelt’s New Deal WPA, the Kennedy-Johnson administration, and the Obama administration. Each time, labor and African Americans elected a president committed to economic fairness and racial justice. Each president began having a Democratic Congress for at least part of his term and a Supreme Court that did not block progressive laws and regulations.

Workers need strong, honest electoral coalitions to elect politicians who will establish and enforce rules that make organizing easier, strengthen labor standards, and make the American economy fairer and more inclusive. In 1976, a quarter of the votes cast in a presidential election came from a union household; today, only one in five do. About two-thirds of union members have voted for Democratic presidents (including 60 percent of white union voters) over the last 50 years, but 85 percent of African Americans did. Nonwhite communities have been the union’s strongest allies. And if labor wants them to support its issues, labor needs to support theirs.

Creating a legal environment that protects union rights and prevents discrimination does not mean the absence of conflicts to negotiate. The world is complicated, and some widely held principles of fairness require reconciliation. A particularly thorny example involves the principle of equal opportunity (every person should have the chance to prove themselves capable and committed) versus the principle of seniority (people who have demonstrated competence in and commitment to a job should be rewarded). This potential conflict can play out through a racial, gender, or simple “new worker” filter.

In a business traditionally staffed by white men, management has a blind spot, deliberate or unconscious bias, to recruit individuals who look like themselves. New factory workers are often recruited through the informal and personal networks of the existing staff. This nepotism is how implicit (unconscious) bias operates. Management must change its recruitment practices and no longer give preference to the friends or relatives of current employees. To the existing workforce, this change could feel like a lost benefit (giving the first option in hiring friends and family). To a nonwhite worker, this would look like favoritism and blocked opportunities.

Currently, union workers with the most seniority in many companies are still more likely to be white and male than nonwhite and female. In this situation, what happens when layoffs occur? According to the seniority principle, those who have been on the job the longest stay. But what if their tenure is longer because others were systematically excluded from the hiring process? Those not allowed to compete for work are penalized for not getting into the job earlier. “Last hired, first fired” means people are punished because of society’s history of racial discrimination. In the 21st-century Recession, many businesses were failing.

Management demanded benefits and wage give-backs in contract negotiations; some pushed a “two-tiered” system: the employees with the longest tenure were allowed to retain their previously negotiated wages and benefits, but new workers had to work for less. These arrangements weakened labor solidarity, and the wage-raising impacted collectively bargained contracts. Those covered everyone equally across a factory, an industry, and a local labor market. The good news is that as the labor market has tightened and there are new contracts, unions have worked hard to return to equal wage and benefit packages.

Promoting equal opportunity and ensuring that working people can join a union to represent them in their jobs to enforce labor laws and standards is not a magic cure-all for racial or gender prejudice. When the number of good union jobs declines, competition increases, creating tensions across racial and gender lines. Better training of police officers, community policing, and body cameras will not prevent racial profiling and the too-quick resort to violence by every police officer.

The MeToo movement showed that the solutions to these thorny issues will be found as we talk to each other, practice fundamental empathy, and share our fears and aspirations at work, in our union halls, and our neighborhoods. This solidarity unionizes workers at Amazon and Starbucks. Police violence against black people has been a problem in America since slavery brought Africans here. State violence was also a problem for striking union members a century ago. (Some observers said they would not have been shot if the workers had not been striking.) Every successful social reform movement in American history—including the labor movement—began when Americans stood up and fought together for a better future.

This century, the activism of young African Americans and others that started in 2012 with the killing of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, the 2020 killing of George Floyd, the 2022 Supreme Court ruling on abortion, and more were inspired by the same sentiments that motivated early unionists: “This is wrong. We won’t accept this anymore. Our lives matter, and we have a right to expect more.” Promoting equal opportunity and ensuring that working people can join a union representing them on their jobs to enforce labor laws and standards is not a magic cure-all for deep-seated racial prejudice.

When the number of good union jobs declines, the competition increases and can play out across racial lines. Better training of police officers, community policing, and body cameras will not prevent racial profiling and the too-quick resort to violence by every police officer. The solutions happen as we talk to each other, practice radical empathy, and share our fears and aspirations at work, in our union halls, and our communities.