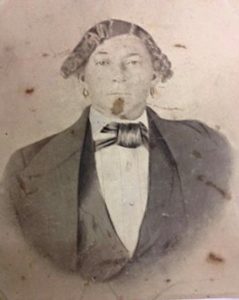

Edmund E. Wysinger

*The birth of Edmond Edward Wysinger is celebrated on this date in 1816. He was a Black Native American pioneer.

He was born in South Carolina, the son of a Cherokee woman and an African slave. In the early part of 1849, at the age of 32, Wysinger and his German owner made the long, perilous trip through Indian territory by ox-team Conestoga wagon to Grass Valley, California, by way of Donner Pass, arriving around October at the height of the California Gold Rush.

"Wysinger took on the last name of his owner; his original Native American name was Bush. After arriving in California's Mother Lode Gold Belt, Wysinger, with a group of 100 or more Black miners, was surface mining in and around Mormon, Mokelumne Hill, Placerville, and Grass Valley. Mokelumne Hill was called "Moke Hill". A tribe of Miwok Native Americans first inhabited the regionknown asd "Mokelumne", which translates to " people of Mokel. "Moke Hill began to grow after gold was discovered in 1848. Place names like Negro Hill, Negro Bar (a large sand bar located on the south bank of the lower American River), and Negro Flat attest to blacks in California."

Wysinger took on the last name of his owner; his original Native American name was Bush. After arriving in California's Mother Lode Gold Belt, Wysinger, with a group of 100 or more Black miners, was surface mining in and around Mormon, Mokelumne Hill, Placerville, and Grass Valley. Mokelumne Hill was called "Moke Hill". A tribe of Miwok Native Americans first inhabited this region called "Mokelumne", which means people of Mokel. "Moke Hill" began to grow after gold was discovered in 1848. Place names like Negro Hill, Negro Bar (a large sand bar located on the south bank of the lower American River), and Negro Flat attest to blacks in California.

Wysinger mined at Mokelumne, Murphy's Camp, Diamond and Mud Springs, Grass Valley, Negro Bar and other mining districts. It took him about a year to buy his freedom for $1,000. In 1853, Alfred and Susan Hines Wilson arrived in Miles Creek, Mariposa County, California, from Wayne County, Missouri, traveling first to Texas and then to California by ox team. More than 100 wagons in the ox-driven team lasted from March to December 1853. In Merced, Edmond Wysinger met and married their daughter, Penecia. Around 1862, the family moved to Visalia, California, where eight children were born: six boys, Jesse, Arthur, James, Reuben, Hervey, Marion, and two girls, Martha and Bertha.

In 1862, Visalia was deeply divided by the American Civil War, with many siding with the South. Despite the turmoil, Wysinger stayed in the community as a self-educated man and worked as a laborer and part-time preacher. He stressed the importance of education for his children. He tried to admit his son Arthur to a regular public school. Still, he was refused, resulting in him entering a suit against the county school board of education in the Supreme Court of the State of California in October 1888. On March 1, 1890, the California Supreme Court, in Wysinger vs. Crookshank, reversed a lower court decision and ordered that 12-year-old Arthur Wysinger be admitted to Visalia's regular school system.

Suppose the state's people desired separate but equal schools for citizens of African descent and Indians. In that case, their wish may be accomplished by laws enacted by the law-making department of the government, or existing constitutional provisions. Until Wysinger, this course had not been pursued, as the law stood in 1890, and the powers granted to boards of education and school trustees, under Section 1617 of the Political Code, did not include the right claimed by the Visalia Board of Education. The laws segregating Chinese children (see United States v. Wong Kim Ark) remained on the books probably because it was the general impression that the Fourteenth Amendment forbade only discriminatory laws aimed at African Americans and Native Americans in the United States Constitution. Edmond Edward Wysinger died in 1891.