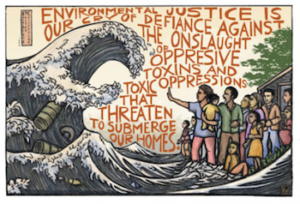

*On this date in 2011, World Environmental Health Day, Environmental racism is affirmed; a culture to protect the environment.

This environmental justice movement developed in the United States throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The term describes environmental injustice within a racialized context in practice and policy. In the United States, environmental racism criticizes inequalities between urban areas after the white flight. Internationally, environmental racism can refer to the effects of the global waste trade, such as the negative health impact of the export of electronic waste to China from developed countries.

The term was coined in 1982 by Benjamin Chavis, previous executive director of the United Church of Christ (UCC) Commission for Racial Justice. He addressed hazardous polychlorinated biphenyl waste in the Warren County PCB Landfill, North Carolina (his home state). Chavis defined the term as racial discrimination in environmental policymaking, the enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of color for toxic waste facilities, the official sanctioning of the life-threatening presence of poisons and pollutants in our communities, and the history of excluding people of color from the leadership of the ecology movements.

North American Environmental racism can be traced back around 500 years with the arrival of the Europeans and their displacement of Native Americans to take their land. The Environmental Justice Movement was rooted around the same time as the 20th-century American Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement influenced the mobilization of people by echoing the empowerment and concern associated with political action. Here, the civil rights agenda and the environmental agenda are met. However, environmental organizations such as the Sierra Club distanced themselves from the Warren County case because of their unwillingness to risk technical support when dealing with a very social issue. Workplace neglect led to Rufus Stokes patenting his Exhaust Purifier in 1968, which exemplifies a Black inventor's attempt to fix the environment that affected his and all communities.

Acknowledging environmental racism prompted the environmental justice social movement that began in the 1970s and 1980s in the United States, including the formation of the African American Environmental Association. While ecological racism has been historically tied to the environmental justice movement, the term has been increasingly disassociated over time. In response to cases of environmental racism, grassroots organizations and campaigns have brought more attention to environmental racism in policy-making and emphasized the importance of having input from non-whites in policy-making.

Although the term was coined in the US, environmental racism also occurs globally. Examples include the exportation of hazardous wastes to poor countries in the Global South with lax environmental policies and safety practices. Marginalized communities that do not have the socioeconomic and political means to oppose large corporations are at risk of environmentally racist practices that are detrimental and sometimes fatal to humans. Economic status and political positions are crucial factors in environmental problems because they determine where a person lives.

Another growing concern is the export of hazardous waste to third-world countries. Between 1989 and 1994, an estimated 2,611 metric tons of hazardous waste was exported from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries to non-OECD countries. Two international agreements were passed in response to the growing exportation of hazardous waste into their borders. The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was concerned that the Basel Convention adopted in March 1989 did not include a total ban on the transboundary movement of hazardous waste.

In response to their concerns, on January 30, 1991, the Pan-African Conference on Environmental and Sustainable Development adopted the Bamako Convention banning the import of all hazardous waste into Africa and limiting their movement within the continent. In September 1995, the G-77 nations helped amend the Basel Convention to ban the export of all hazardous waste from industrial countries (mainly OECD countries and Lichtenstein) to other countries. A resolution was signed in 1988 by the OA) which declared toxic waste dumping to be a “crime against Africa and the African people.” Soon after, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) passed a resolution allowing penalties, such as life imprisonment, for those caught dumping toxic waste.

Globalization and the increase in transnational agreements introduce possibilities for cases of environmental racism. For example, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) attracted US-owned factories to Mexico, where toxic waste was left in the Colonia Chilpancingo community and was not cleaned up until activists called for the Mexican government to clean up the waste. In the 21st century, Environmental justice movements have become an important part of world summits. This issue gathers attention and features various people, workers, and societal levels working together. Concerns about globalization can bring together many stakeholders, including workers, academics, and community leaders for whom increased industrial development is a common denominator”.

The 2002 No Fear Act exemplifies the need to protect people working within environmental agencies. Many policies can be expounded based on the state of human welfare. This occurs because environmental justice aims to create safe, fair, and equal opportunities for communities and ensure things like redlining do not happen. With all of these unique elements in mind, there are serious ramifications for policymakers to consider when they make decisions. Yet the racial overtone is consistent in locations where non-white and poor people live.

These protective policy practices are not to be assumed in the United States. The 2014 Flint, Michigan, water crisis and the 2022 Jackson, Mississippi, post-flooding water crisis have not been rectified. In 2017, about 1,200 Africatown, Alabama residents launched a lawsuit against International Paper (IP) for improper handling of waste through the decades that contaminated the land and water, and the company did not clean up the site as required after closing the plant.