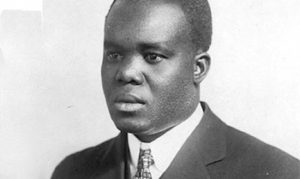

Hubert Harrison

*Hubert Harrison was born on this date in 1883. He was an Afro Caribbean writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist.

Hubert Henry Harrison was born to Cecilia Elizabeth Haines, a working-class woman, on Estate Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies. His biological father, Adolphus Harrison, was born enslaved. As a youth, Harrison knew poverty and learned of African customs and the Crucian people's rich history of direct-action mass struggles. Among his schoolmates was his lifelong friend, the future Crucian labor leader and social activist D. Hamilton Jackson.

Harrison came to New York in 1900 as a 17-year-old orphan and joined his older sister. He confronted racial oppression, unlike anything he had previously known, as only the United States had such a binary color line. In the Caribbean, social relations were more fluid. Harrison was especially "shocked" by the virulent white supremacy lynchings, which were reaching a peak in the South. They were a horror that had not existed in St. Croix or other Caribbean islands. In addition, the fact that blacks and people of color far outnumbered whites in most places meant they had more social spaces in which to operate away from the oversight of whites. Harrison began working low-paying service jobs while attending high school at night. While still in high school, his intellectual gifts were recognized.

At age 20, he became an American citizen and lived in the United States for the rest of his life. In 1907, Harrison obtained a job at the United States Post Office. In 1909, Harrison married Irene Louise Horton. They had four daughters and one son. In his first decade in New York, Harrison started writing letters to the editor of The New York Times and lecturing on such subjects as the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar and Reconstruction. He also criticized Booker T. Washington, whose political philosophy he considered subservient. In 1910, Harrison wrote two letters to the New York Sun that were critical of statements by Washington. Harrison lost his postal employment through the efforts of Washington's powerful "Tuskegee Machine" in events that involved the prominent Black Republican Charles W. Anderson, Washington's assistant Emmett Scott, and New York Postmaster Edward M. Morgan.

Harrison also worked with bibliophile Arthur Schomburg, journalist John E. Bruce, activist Samuel Duncan, the White Rose Home(with educator/activist Frances Reynolds Keyser), and the Colored YMCA. Harrison was an early supporter of the protest philosophies of W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. Particularly after the Brownsville Affair, Harrison became an outspoken critic of the Republican Party. In 1920 Harrison became the principal editor of the Negro World, the newspaper of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Over the next eight months, he developed it into the leading race-conscious, radical, and literary publication of the day. By the August 1920 UNIA convention, Harrison had grown increasingly critical of Garvey.

He criticized Garvey for exaggerations, financial schemes, and the desire for empire. In contrast to Garvey, Harrison emphasized that African Americans' principal struggle was in the United States, not Africa. Harrison contributed to the UNIA's 1920 "Declaration of the Negro Peoples of the World." Though Harrison continued to write for the Negro World into 1922, he looked to develop political alternatives to Garvey. After breaking with Garvey, he lectured on political history, science, literature, social sciences, international affairs, and the arts for the New York City Board of Education. He was one of the first to use the radio to discuss topics. In early July 1923, he spoke on "The Negro and The Nation" over New York station WEAF.

His book and theater reviews and other writings appeared in many of the leading periodicals of the day, including The New York Times, New York Tribune, Pittsburgh Courier, Chicago Defender, Amsterdam News, New York World, Nation, New Republic, Modern Quarterly, Boston Chronicle, and Opportunity magazine. He openly criticized the Ku Klux Klan and the racist attacks of the "Tulsa Race Riot" of 1921. He worked with various groups, including the Virgin Island Congressional Council, the Democratic Party, the Farmer-Labor Party, the single tax movement inspired by Henry George, the American Friends Service Committee, the Urban League, the American Negro Labor Congress, and the Workers (Communist) Party. He was described by activist A. Philip Randolph as "the father of Harlem radicalism" and the historian Joel Augustus Rogers as "the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time."

Harrison played significant roles in the largest radical class and race movements in the 20th-century United States. From 1912 to 14, he was the leading Black organizer in the Socialist Party of America. In 1917 he founded the Liberty League and The Voice, the first organization and newspaper of the race-conscious "New Negro" movement. He was a seminal and influential thinker who influenced a generation of "New Negro" militants, including A. Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, Richard Benjamin Moore, W. A. Domingo, Williana Burroughs, and Cyril Briggs. Harrison later worked with many Virgin Islands-born activists, including Casper Holstein and Frank Rudolph Crosswaith. He was especially active in Virgin Island causes after the March 1917 U.S. purchase of the Virgin Islands and subsequent abuses under the U.S. naval occupation of the islands.

In 1924, he founded the International Colored Unity League (ICUL). He called for "a Negro state" in the U.S. In 1927, Harrison edited the ICUL's Voice of the Negro until shortly before his death. In his last lecture, Harrison told his listeners that he had appendicitis and would be getting surgery. Afterward, he said he would be giving another lecture. He died on the operating table at the age of 44 on December 17, 1927.

Industrial Workers of the World

General Headquarters,

PO Box 13476,

Philadelphia, PA 19101