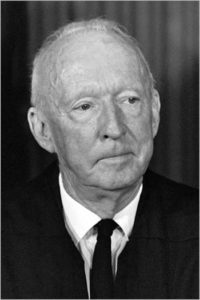

Hugh L. Black

*Hugo Black was born on this date in 1886. He was a white-American lawyer, politician, and judge.

Hugo LaFayette Black was the youngest of the eight children of William Lafayette Black and Martha (Toland) Black. He was born in a small wooden farmhouse in Ashland, Alabama, a poor, rural Clay County town in Appalachia. Black descended from Hugh and Mary Spencer Toland, Protestant emigrants from Ireland in the 18th century, who are buried at the Upper Long Cane Cemetery in Abbeville, South Carolina.

His older brother Orlando suggested that Hugo enroll at the University of Alabama School of Law. After graduating in 1906, he moved back to Ashland and established legal practice, and he soon moved to Birmingham in 1907, where he specialized in labor law and personal injury cases. Because he defended an African American forced into a form of commercial slavery after incarceration, Black was supported by A. O. Lane, a judge connected with the case. When Lane was elected to the Birmingham City Commission in 1911, he asked Black to serve as a police court judge, his only judicial experience before the Supreme Court. In 1912, Black resigned that seat to return to practicing law full-time; in 1914, he began a four-year term as the Jefferson County Prosecuting Attorney.

Three years later, during World War I, Black resigned to join the United States Army. He joined the Birmingham Civitan Club during this time and remained an active member, occasionally contributing articles to Civitan publications. In the early 1920s, Black became a Robert E. Lee Klan No. 1 member in Birmingham before resigning in 1925. In 1937, after his confirmation to the Supreme Court, it was reported he had been given a "grand passport" in 1926, granting him life membership to the Ku Klux Klan. As a senator, Black filibustered an anti-lynching bill. However, Black established a record that was more sympathetic to the civil rights movement during his tenure on the bench.

A member of the Democratic Party and a devoted New Dealer, Black endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 and 1936 presidential elections. Having gained a reputation in the Senate as a reformer, President Roosevelt nominated Black to the Supreme Court. He was confirmed by the Senate by a vote of 63 to 16 (6 Democratic Senators and 10 Republican Senators voted against him). He was the first of nine Roosevelt nominees to the Court and outlasted all except William O. Douglas.

Shortly after Black's appointment to the Supreme Court, Ray Sprigle of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote a series of articles, for which he won a Pulitzer Prize, revealing Black's involvement in the Klan and describing his resignation from the Klan as "the first move of his campaign for the Democratic nomination for United States Senator from Alabama." Sprigle wrote, "Black and the leaders of the Klan decided it was a good political strategy for Black to make the senatorial race unimpeded by Klan membership but backed by the power of the Klan. That resignation [was] filed for the campaign's duration but never revealed to the rank and file of the order and held secretly in the records of the Alabama Realm..." Roosevelt denied knowledge of his KKK membership.

In a radio statement on October 1, 1937, Black said in part, "I number among my friend's many members of the colored race. Certainly, they are entitled to the full measure of protection accorded by our Constitution and our laws ..." Black also said, "I did join the Klan. I later resigned. I never rejoined. ... Before becoming a Senator, I dropped the Klan. I have had nothing to do with it since that time. I abandoned it. I completely discontinued any association with the organization. I have never resumed it and never expect to do so." The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that "fifty million listeners heard the unprecedented speech."

The fifth longest-serving justice in Supreme Court history, Black was one of the most influential Supreme Court justices in the 20th century. He is noted for his advocacy of a textualist reading of the United States Constitution and the position that the liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights were imposed on the states ("incorporated") by the Fourteenth Amendment. Black staunchly supported liberal policies and civil rights during his political career. He joined the majority in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), invalidating the judicial enforcement of racially restrictive covenants. Similarly, he was part of the unanimous Brown v. Board of Education (1954) Court that struck down racial segregation in public schools. Black remained determined to desegregate the South and would call for the Supreme Court to adopt "immediate desegregation" in 1969's Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education. Black wrote the court's majority opinion in Korematsu v. the United States. This decision is an example of Black's belief in the limited role of the judiciary; he validated the legislative and executive actions that led to internment, saying, "it is unnecessary for us to appraise the possible reasons which might have prompted the order to be used in the form it was."

Black also tended to favor law and order over civil rights activism. This led him to read the Civil Rights Act narrowly; his sister-in-law explained that Black was "mortally afraid" of protesters. Black opposed the actions of some civil rights and Vietnam War protesters and believed that legislatures first and courts second should be responsible for alleviating social wrongs. Black once said he was "vigorously opposed to efforts to extend the First Amendment's freedom of speech beyond speech" to conduct. Black was one of the Supreme Court's foremost defenders of the "one man, one vote" principle. At the same time, Black did not believe that the equal protection clause made poll taxes unconstitutional.

During his first term on the Court, he participated in a unanimous decision to uphold Georgia's poll tax in the case of Breedlove v. Suttles. Then, twenty-nine years later, he dissented from the Court's ruling in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections (1966), invalidating the use of the poll tax as a qualification to vote, in which Breedlove was overturned. He criticized the Court for exceeding its "limited power to interpret the original meaning of the Equal Protection Clause" and for "giving that clause a new meaning which it believes represents a better governmental policy." He also dissented from Kramer v. Union Free School District No. 15 (1969).

Regarding Brown v. Board of Education, the plaintiffs were represented by Thurgood Marshall. A decade later, on October 2, 1967, Marshall became the first African American appointed to the Supreme Court and served with Black on the Court until Black's retirement on September 17, 1971. Thurgood Marshall wanted to be sworn in as an Associate Justice by Hugo L. Black. He died on September 25, 1971.