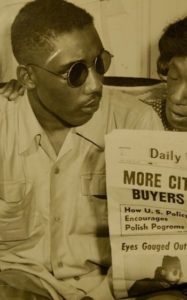

Issac Woodard Jr.

*Isaac Woodard Jr. was born on this date in 1919. He was a decorated Black World War II veteran and hate crime victim.

Woodard was born in Fairfield County, South Carolina, and grew up in Goldsboro, North Carolina. He attended local segregated schools, often underfunded for Blacks during the Jim Crow years. On October 14, 1942, the 23-year-old Woodard enlisted in the U.S. Army at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina. He served in the Pacific Theater as a longshoreman in a labor battalion and was promoted to sergeant. He earned a battle star for his Asiatic-Pacific Theater Campaign Medal by unloading ships under enemy fire in New Guinea. He received the Good Conduct Medal, the Service Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal awarded to all American participants. He received an honorable discharge on February 12, 1946.

That day, Woodard Jr. was on a Greyhound Lines bus traveling from Camp Gordon in Augusta, Georgia, where he had been discharged en route to rejoin his family in North Carolina. When the bus reached a rest stop just outside Augusta, Woodard asked the bus driver if there was time for him to use a restroom. The driver grudgingly acceded to the request after an argument. Woodard returned to his seat from the rest stop without incident, and the bus departed. The bus stopped in Batesburg (now Batesburg-Leesville, South Carolina), near Aiken in the Jim Crow south.

Though Woodard had caused no disruption, the driver contacted the local police (including Chief of Police Lynwood Shull), who forcibly removed Woodard from the bus. After demanding to see his discharge papers, several policemen, including Shull, took Woodard to a nearby alleyway, where they beat him repeatedly with nightsticks. They then took Woodard to the town jail and arrested him for disorderly conduct, accusing him of drinking beer in the back of the bus with other soldiers. The attack left Woodard permanently blind.

The following morning, the police sent Woodard before the local judge, who found him guilty and fined him fifty dollars. The soldier requested medical assistance, but it took two more days for a doctor to be sent to him. Not knowing where he was and suffering from amnesia, Woodard ended up in a hospital in Aiken, South Carolina, receiving substandard medical care. Three weeks after he was reported missing by his relatives, Woodard was discovered in the hospital. He was immediately rushed to a US Army hospital in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Though his memory had begun to recover by that time, doctors found both eyes were damaged beyond repair. Though the case was not widely reported, it was soon covered extensively in major national newspapers. The NAACP worked to publicize Woodard's plight, campaigning for the state government of South Carolina to address the incident, which it dismissed.

On his ABC radio show, Orson Welles Commentaries, actor and filmmaker Orson Welles crusaded for the punishment of Shull and his accomplices. A month after the beating, calypso artist Lord Invader recorded an anti-racism song for his album Calypso at Midnight; it was entitled "God Made Us All," with the last line of the song directly referring to the incident. Later that year, folk artist Woody Guthrie recorded "The Blinding of Isaac Woodard," which he wrote for his album The Great Dust Storm.

On September 19, 1946, seven months after the incident, NAACP Executive Secretary Walter Francis White met with President Harry S. Truman to discuss the Woodard case. The following day, Truman wrote a letter to Attorney General Tom C. Clark demanding that action be taken to address South Carolina's reluctance to try the case. Six days later, Truman directed the United States Department of Justice to open an investigation into the case. A short investigation followed, and Shull and several of his officers were indicted in U.S. District Court in Columbia, South Carolina. It was within federal jurisdiction because the beating occurred at a bus stop on federal property, and Woodard was in uniform with the armed services at the time.

The case was presided over by Judge Julius Waties Waring. By all accounts, the trial was a travesty. The local U.S. Attorney handling the case failed to interview anyone except the bus driver, a decision Waring, a civil rights proponent, believed was a gross dereliction of duty. Waring would later write about how the case was handled locally. The behavior of the defense was no better. When the defense attorney began to shout racial epithets at Woodard, Waring had it stopped immediately. During the trial, the defense attorney told the jury, "If you rule against Shull, let this South Carolina secede again."

After Woodard gave his account of the events, Shull firmly denied it, claiming that Woodard had threatened him with a gun and that Shull had used his nightclub to defend himself. During this testimony, Shull admitted that he repeatedly struck Woodard in the eyes. After thirty minutes of deliberation, Shull was found not guilty on all charges despite his admission that he had blinded Woodard. This ruling exemplified the racial intersectionality in state versus federal laws. Truman subsequently established a national interracial commission, made a historic speech to the NAACP and the nation in June 1947 in which he described civil rights as a moral priority, submitted a civil rights bill to Congress in February 1948, and issued Executive Orders 9980 and 9981 on June 26, 1948, desegregating the armed forces and the federal government.

Woodard moved north after the trial and lived in the New York City area for the rest of his life. Isaac Woodard died at age 73 in the Veterans Administration Hospital in the Bronx on September 23, 1992. He was buried with military honors at the Calverton National Cemetery (Section 15, Site 2180) in Calverton, New York.