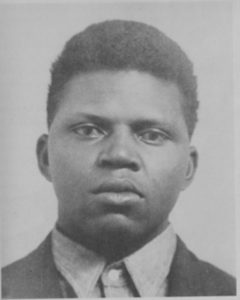

Odell Waller

*The birth of Odell Waller is celebrated on this date in 1917. He was a Black sharecropper, executed for the fatal shooting of his white landlord.

Odell Waller was born in Gretna, Virginia, to Dollie Jones and an unknown father, who died shortly after his birth. Jones gave the boy to her sister Annie Waller and Annie's husband, Willis Waller, to adopt, and Odell considered Annie his mother. He completed three years of high school but was later forced to leave to work on the farm. From 1935 to 1938, he was convicted of seven offenses, including assault, reckless driving, bootlegging, and carrying a concealed razor. In January 1939, he married a woman named Mollie.

During the Great Depression, the Wallers fell behind on the mortgage for their farm, and after Willis died in 1938, the bank foreclosed. Annie and Odell then agreed to become sharecroppers for a white landlord, Oscar Davis. The relationship quickly soured. Davis was also a sharecropper, and when his landlord reduced Davis' land allotment, Davis reduced that of the Wallers to only 2 acres. The Wallers accused Davis of failing to pay Annie an agreed $7.50 for caring for Davis' ill wife for three weeks; when the Wallers refused to work in Davis' fields, Davis evicted them. Following the eviction, someone on the Davis farm mutilated one of the Wallers' dogs.

After Annie's cousin Robert helped her harvest the farm's wheat, Davis took the whole crop rather than give the Wallers their share. In April 1940, Odell Waller had taken a job constructing electrical lines in Maryland, but he returned on the weekend of July 13–14 to investigate the worsening situation. On July 15, 1940, he drove to Davis's farm to get the wheat with Annie, relatives Archie Waller and Thomas Younger, and a friend named Buck Fitzgerald. He also brought along a .32 caliber pistol.

The subsequent events remain in dispute. Henry Davis, a teenage Black employee of Oscar Davis, maintained that Odell Waller had fired at Oscar Davis without provocation or warning, hitting him four times. Oscar Davis's sons testified that their father had started before he died that Waller had shot him without cause. One son added that Davis had said Waller had continued to shoot after Davis had fallen to the ground. The testimony of other witnesses, including Waller's relatives, was inconclusive, as they were too distant to hear the conversation between Waller and Davis.

Waller stated that Davis had refused to let him take the Waller family's share of the wheat and had reached for his pocket as if to draw a gun; Waller then shot him. Davis escaped through the cornfield after being shot and was taken to the hospital, where he died on July 17. Afraid he would be lynched, Waller fled to Columbus, Ohio, but was arrested there at the home of an uncle after a manhunt involving police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

During Waller's trial, which began on September 19, 1940, he was represented by the Revolutionary Workers League (RWL). The group compared the trial to that of the Scottsboro Boys and began criticizing the racism and economic conditions of Waller's rural Virginia county. Historian Richard B. Sherman argues that the group brought negative publicity to Waller's trial by creating the perception that "radical outsiders" were behind his defense. A socialist labor rights organization, the Workers' Defense League (WDL), offered to take over the defense and public campaign to avoid the stigma of communism from influencing Waller's case, but the RWL rebuffed them. The defense was given only three days to prepare Waller's defense. After selecting an all-white jury composed only of citizens who could pay the poll tax, the defense moved that the case be dismissed because Waller was "deprived of a trial by a jury of his peers." However, it failed to submit evidence that this was the case, a factor that would prove crucial in later unsuccessful appeals.

The judge dismissed the motion and made a tactically questionable motion that the judge himself was prejudiced in the case and should withdraw. The testimony of Henry Davis and Oscar Davis's sons proved damning. On September 27, 1940, after less than an hour's deliberation, the jury found Waller guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced him to death, a verdict praised by the Virginia press covering the trial. His execution was scheduled for December 27 of that year. After the trial, the RWL agreed to pass responsibility for the public campaign and legal appeals to the WDL, provided that the case continues to be handled "on a class struggle basis," with attention to national issues and Waller's specific situation. Eager to help Waller, the WDL reluctantly agreed to the terms. The organization assumed control of the case in November 1940 and immediately began fundraising on Waller's behalf. Pauli Murray, a young woman new to the organization, was dispatched on a national fundraising tour, accompanied at times by Annie Waller.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) joined the case the same month, as did the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, giving the case national publicity. Attorney Martin A. Martin (President of the Danville NAACP) developed information that both the grand jury that indicted Waller and the petit jury that convicted him was composed only of white men who paid polled taxes (thus excluding most blacks and Waller's peers). However, the county clerk initially gave him the runaround. The groups hoped the case would lead the US Supreme Court to rule that the poll tax was unconstitutional. In December, Virginia Governor James H. Price granted Waller his first stay of execution for three months, giving the new defense additional time to study the case.

On March 28, 1941, efforts by novelist Pearl S. Buck, philosopher John Dewey, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt joined the cause. President Franklin D. Roosevelt also made a private appeal on Waller's behalf to Virginia Governor Colgate Darden. Though the campaign won several postponements of the sentence, Waller was finally executed on July 2, 1942. The case failed to overturn the poll tax but led to reform of Virginia's penal system and motivated Pauli Murray to begin her career in civil rights law. At the time of his execution, Waller had been on death row for 630 days.

His funeral was held on July 5 and was attended by 2,500 people. Only one white person, WDL Secretary Morris Milgram, attended. Other whites had been asked not to come; a reporter wrote of the exclusion that "[the black community] did not want 'Odell Waller's murderers' to look on his face in death." The Waller case attracted national attention and expressly highlighted racial identity as a component of criminal justice, press coverage, and regional exceptionalism.