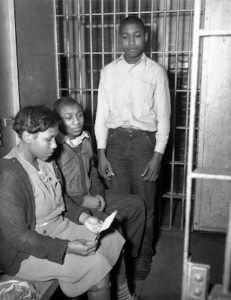

Ms. Ingram and two of her sons

*Rose Lee Ingram was born on this date in 1902. She was a Black farmer (sharecropper) and widowed mother of 12 children, who was at the center of one of the most explosive capital punishment cases in United States history.

Ingram farmed adjoining lots in Georgia with white sharecropper John Ed Stratford. Ingram bred Stratford’s livestock. On November 4, 1947, Stratford confronted Ingram, accusing her of allowing her livestock to roam freely on his land. When Ingram reminded Stratford that their landlord owned the livestock and the land, he struck her with a gun. Several of Ingram’s sons defended her, and Stratford was killed. Ingram, along with her sons Charles (17), Wallace (16), Sammie Lee (14), and James (12), was arrested. James was eventually released.

Although the prosecution suggested that the confrontation between Stratford and Ingram owed to a conflict over the livestock, later accounts indicated that Stratford was enraged because Ingram had repeatedly objected to his sexual harassment of her. Their defense argued that Ingram’s sons killed Stratford in self-defense. The trial, held on January 26, 1948, in Ellaville, Georgia, lasted one day; Judge W. M. Harper presided over the case. The attorney representing Ingram (and appointed to her the morning of the trial) was S Hawkins Dyke. According to Charles H. Martin, the release of Charles Ingram in his trial the following day came due to insufficient evidence.

The sentencing of Ingram and her two sons to die in the electric chair was handed down by an all-white jury on February 7, 1948. When their executions were scheduled for February 27, 1948, less than three weeks later. The country erupted in protests against the trial and the sentences, which had been conducted hastily and in secrecy. In response to national protests led by Sojourners for Truth and Justice, their sentences were commuted to life in April 1948. A second wave of protests ensued after the Georgia Supreme Court upheld the Ingrams’ life sentences.

Despite continued protests from Civil Rights organizations based on the extenuating circumstances (e.g., Mr. Stratford had sexually assaulted Ingram and her children were responding in self-defense), in 1952, the Georgia pardon and parole board refused to free Ingram and her two sons. When Sojourners for Truth and Justice came to visit Georgia Governor Herman Talmadge in January 1953 to plead for their release, they were turned away by the governor’s wife.

In 1955, the Ingrams were denied parole again. Following Ingram's release from prison, she lived in Atlanta, Georgia, until her death. The Civil Rights Congress and Sojourners defended the Ingrams for Truth and Justice. As historian Erik S. McDuffie notes, "The case galvanized Black left feminists, highlighting the specific forms of oppression experienced by Black women, as well as foregrounding the history of white men’s sexual violence against Black women."

According to McDuffie, “Ingram’s case represented in glaring terms the interlocking systems of oppression suffered by African American women: the painful memories of and the continued day-to-day sexual violence committed against black women’s bodies by white men, the lack of protection for and the disrespect of black motherhood, the economic exploitation of black working-class women, and the disenfranchisement of black women in the Jim Crow South.” In 1959, Rosa and her sons were finally granted parole. Black progressive women led the global campaign to free Ingram. Rose Lee Ingram died on August 2, 1980.