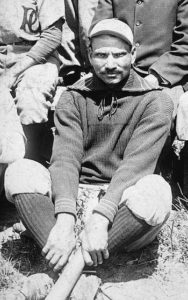

Sol White (1902)

*"Sol" White was born on this date in 1868. He was a Black professional baseball infielder, manager, writer, and executive, and one of the pioneers of the American Negro Leagues.

Born in Bellaire, Ohio, King Solomon White's early life is not well-documented. According to the 1870 and 1880 U.S. Census, his family (parents and two oldest siblings) came from Virginia. His father, Saul Solomon White, apparently died when White was very young. White's mother, Judith, supported Sol and four siblings with her work as a "washerwoman." White "learned to play ball as a youngster." As a teenager, White was a fan of the Bellaire Globes, local amateurs. White quickly made a name for himself as a ballplayer. By age 16, he "attracted the attention of managers of independent teams throughout the Ohio Valley, and his services were in great demand."

Originally a shortstop, White eventually "developed into a great all-around player filling any position from catcher to right field." In 1887, he joined the Pittsburgh Keystones of the National Colored Base Ball League as a left fielder and later second baseman. He then joined the Wheeling (West Virginia) Green Stockings of the Ohio State League and batted .370 with a slugging percentage of .502 as the team's third baseman. In the off-season, the Ohio State League renamed itself the Tri-State League and banned Black players, including White.

Weldy Walker, a Black catcher for the league's Akron club, wrote an open letter to league officials protesting the decision. It was published in Sporting Life in March 1888, and within a few weeks, the ban was rescinded. White resigned and was sent to join his team on the road, but the Wheeling manager refused to accept him and released him.

He rejoined the Pittsburgh Keystones and played in a "Colored Championship" tournament held in New York City, in which the Keystones finished second to the Cuban Giants. Along with Walter Schlichter, a sportswriter for the Philadelphia Item, and Harry Smith, a baseball writer for the Philadelphia Tribune, White founded the Philadelphia Giants in 1902. He served as the team's captain and manager. The Giants were initially paid on a profit-sharing "cooperative plan," but in 1903, White reorganized the team and put all the players on salary. The Giants lost a playoff for the colored championship to the Cuban X-Giants and their ace pitcher, Rube Foster.

The following season, White signed Foster, and the Philadelphia Giants won a championship series against the X-Giants, which was five games to two. For 1905, White brought in Home Run Johnson of the X-Giants and made the Philadelphia Giants into what he considered "the strongest organization of the time." The Giants went undefeated against New England League teams and swept four games from the Newark International League team. The Giants played a total of 158 games, winning 134, losing 21, and tying 3. The baseball promoter and team owner Nat Strong declared the 1904-1905 Philadelphia Giants "the best team in the game's history."

White married Florence Fields on March 15, 1906. Their first child, a son named Paran Walter White, was born later that year. A second son, a boy, died when he was only two days old in August 1907. Paran died of kidney disease in April 1908. A third child, a daughter, Marion, lived to adulthood and survived her father. Florence and Sol White appear to have become separated at some point before 1930.

Sol White is perhaps best known for writing History of Colored Base Ball, also known (on the title page) as Sol White's Official Base Ball Guide. A small, 128-page, soft-covered pamphlet, it was sold at Philadelphia Giants games in the spring of 1907. The first chapter, "Colored Base Ball," begins with the organization in 1885 of the first professional colored baseball team, discusses the brusque removal of all black players from predominantly white teams during the next four years, and then traces the growing strength of "colored baseball" into the early years of the 20th century. This short book-within-a-book is history, but it can also be described as an almanac, a scorecard, an archive, a who's who of Black baseball up to 1907.

In addition to White's narrative of the history of black professional teams, the book featured chapters on "Colored Baseball as a Profession," "The Color Line," and "Managers' Troubles," among others. Rube Foster, one of White's former players, contributed a chapter on "How to Pitch." Home Run Johnson wrote a short essay on the "Art and Science of Hitting." The book also included 57 photographs of players, managers, and owners, many of whom were not found elsewhere. White's History of Colored Base Ball was the first book devoted to black professional baseball, and it would remain the only one for more than 60 years until Robert W. Peterson published Only the Ball Was White in 1970. Today, only five copies are known to exist.

Sol White's career as a baseball writer would continue with a series of articles on "colored baseball" in the Cleveland Advocate, a black newspaper, in 1919. After he moved to the East Coast in the 1920s, he wrote articles and columns for the New York Age and the New York Amsterdam News. In 1927, the Pittsburgh Courier reported that White "has a new book he would like to publish, a kind of the second edition to his old one, bringing the game from 1907 down to date, and if there is anybody anywhere in sports circles who thinks enough of what has gone before to help Sol print his record, he will be glad to hear from them. This record will undoubtedly prove valuable in years to come." This second book on black baseball by Sol White never appeared.

Sol White died on August 26, 1955, at age 87, in Central Islip, New York. When White was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006, no family member was present, so Commissioner of Baseball Bud Selig accepted his plaque on the family's behalf. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Frederick Douglass Memorial Park in the Oakwood neighborhood of Staten Island, New York City, until 2014, when the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project installed a new headstone at his burial site. He remains the only Hall of Famer buried on Staten Island.