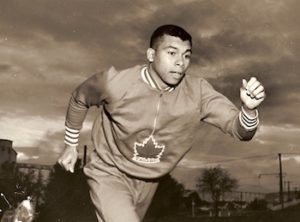

Harry Jerome

*Harry Jerome was born on this date in 1940. He was a Black Canadian Olympic athlete and businessman.

Harry Winston Jerome was born in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and was one of five children of Harry Sr. and his wife, Elsie. His grandfather was John Howard Armstrong. In the 1950s, Jerome and his family eventually moved to North Vancouver, where they were the only Black people in their neighborhood. As his athletic legend grew, Jerome avoided the limelight and set the standard as the world's fastest man (at the time) with records in the 100 meters, 100-yard dash, and indoor 60 meters. He also helped to establish a world record in the 4 x 100-meter relay.

Jerome received numerous accolades throughout his athletic career at the University of Oregon. He represented Canada at two Pan American Games and twice at the Commonwealth, and he would represent Canada on three occasions at the Olympics. Jerome suffered a career-threatening injury at the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth, Australia, completely severing his left quadriceps muscle; most orthopedic surgeons said he would never run again. Months of determination, physiotherapy, and courage set the stage for what would be known as "the greatest comeback." In 1964, Jerome returned to track and field's largest stage, the Tokyo Olympics. Bearing a 30-centimeter scar on his left thigh, Jerome captured bronze in the 100 meters.

He followed his Olympic showing with gold medal performances at the Pan American and Commonwealth Games. At the University of Oregon, he coupled his athletic achievements with academic success, earning both undergraduate and graduate degrees in Science. Despite his athletic achievements, Jerome was always conscious of Black Canadians' challenges.

He also used his athletic notoriety to create opportunities for others, "using the fame and contacts he made in the sports world to get equipment for young athletes who could not afford them." Jerome also did extensive work to create opportunities for Blacks beyond sports. He was a vocal opponent of the misrepresentation of Black Canadians in Canadian television. He asked that licenses be suspended "if stations could not justify neither having Blacks as on-air personalities nor airing stories about the [African Canadian] community."

He fought to remove wage discrimination barriers against Blacks and tried to improve the mainstream's perception of the African Canadian community. In one instance, he wrote to the major department stores and questioned the lack of Black models in their catalogs and as clerks in their stores. Despite his stature in the greater community, Jerome never forgot about his upbringing or role in bringing about change.

After he retired from competition in 1968, Jerome worked with the Federal Ministry of Sport. He designed a series of cartoon manuals for coaching instructions and game rules for children and created the Premier Sports Program for use in schools in British Columbia. Jerome also introduced weight training for sprinters. He was named British Columbia's Athlete of the Century and, in 1971, received the Order of Canada award.

Harry Jerome died on December 7, 1982. Despite his untimely passing, he left a considerable legacy that is a source of pride for all Canadians. In 1988, a statue was erected in his honor along the sea wall of Vancouver's Stanley Park, and both the University of Oregon and the province of British Columbia bear recreational facilities in his name as a testament to his greatness. Jerome, the premier Canadian track athlete of his time, had athletic successes partnered with academic excellence and social consciousness.