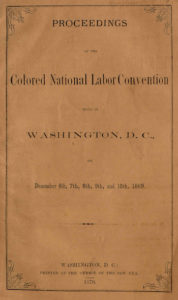

CNLU Convention Pamphlet

*The Colored National Labor Union (CNLU) first met on this date in 1869. Established during a 4-day convention, the CNLU was formed by Blacks to organize their labor collectively nationally.

The CNLU, like other labor unions in the United States, was created to improve the working conditions and quality of life for its members. During the 1869 NLU convention, a motion was passed claiming that the organization did not recognize color; many local unions ignored this ruling and remained segregated. Due to the use of Black laborers as strikebreakers, there was a great deal of resentment from mostly white unions, who saw them as competitors. This resentment went both ways, as white strikebreakers were often employed when Black workers went on strike.

Another issue was that the white working class was the base for violent white supremacist groups, making unity between the two races difficult. There were also disagreements between black and white workers regarding the priorities of labor unions, with white workers more focused on establishing political power and currency reform. In contrast, black workers were more concerned with the ability to own and develop property. As such, the Black workers broke apart from the N.L.U. and had their convention later that year, resulting in the creation of the Colored National Labor Union. According to its constitution, the organization's official name was The National Labor Union. The word "colored" was added to the last name by the public media of the time, thus labeling it the "Colored National Labor Union."

The "Colored" National Labor Union was a post-American Civil War organization founded in December 1869 by an assembly of 214 African American mechanics, engineers, artisans, tradesmen, and trades-women, and their supporters in Washington, D.C. They pursued equal representation for African Americans in the workforce. Isaac Myers, its first president, organized the labor union; Frederick Douglass was the president of the CNLU in 1872. Douglass's newspaper, The New Era, was chosen as the official organ of this National Labor Union. The CNLU sent delegates to the 1870 National Labor Convention. Still, following the N.L.U.'s rejection of Black abolitionist attorney John M. Langston's admission during the conference, the CNLU broke off most of its contact with the N.L.U.

During the first convention of the CNLU in December 1869, 214 delegates met and wrote a petition to Congress. This petition asked Congress to split public land within the South into farmland to be used by low-income Black farmers. It also requested that black farmers get a low-interest loan from the government. Another petition in 1871 asked for the commission of an investigation into "Conditions of Affairs in the Southern States." Neither of these petitions made much, if any, impact on the treatment of black workers in the South. The Colored National Labor Union also established the Bureau of Labor in Washington, D.C. The Bureau of Labor was designed to assist workers of color in organizing throughout the country. As President of the CNLU, Isaac Meyers traveled throughout the country, encouraging the organization of black workers and attempting to convince white labor unions to allow nonwhite workers within their organizations.

On his trips, he often specifically focused on mechanics and mechanic unions, as he believed that white mechanic labor unions were explicitly designed to withhold specific positions from black workers. Unfortunately, upon the CNLU's second annual convention, Myers stated that the organization was not as successful as it had hoped. He claimed that the educational and financial resources of CNLU and the Bureau of Labor were insufficient. He noted that the Ku Klux Klan's power in the South prevented the organization of Black laborers in certain areas. While Meyers had warned against the CNLU becoming a primarily political body, as opposed to a trade union party, the election of Frederick Douglass in 1871 reflected the influx of political figures within the organization. Over time, the CNLU became increasingly more political. Hence, it became a branch of the Republican party, resulting in less trade union activity and less contact with trade unions across the country.

By 1872, the CNLU had ceased most of its operations and would eventually disband, just as the N.L.U. had when their designation as a political party fractured their organization. Blacks were excluded from some existing labor unions, such as when white workers formed the National Labor Union (N.L.U.). William Sylvis, president of the N.L.U., made a speech in which he agreed that there should be "no distinction of race or nationality" within the ranks of his organization. In 1869, several Black delegates were invited to the annual meeting of the N.L.U., including Isaac Myers, a prominent organizer of Black laborers. At the convention, he spoke eloquently for solidarity, saying that white and Black workers should organize together for higher wages and a comfortable standard of living.

However, the white unions refused to allow Blacks to join their ranks. In response, Myers met with other black laborers to form a national organization. Additional goals of the CNLU, representing Black laborers in 21 states, were the issuance of farmland to poor African Americans in the South, government aid for education, and new non-discriminatory legislation to help struggling Black workers. It was not until after World War II in the 1940s that the U.S. government stepped in and encouraged the development of the Fair Employment Practices Commission.