*The Cotton Club opened on this date in 1923. From 1923 to 1940, this popular segregated New York City nightclub exemplified how American racial intersectionality and inequity lived together. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue (1923 to 1935) and briefly in the midtown Theater District (1935 to 1940).

In 1920, heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson rented the upper floor of the building on the corner of 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue in the heart of Harlem and opened an intimate supper club called the Club Deluxe. Owney Madden, a prominent white bootlegger and gangster from England, took over the club after his release from prison in 1923 and changed its name to the Cotton Club. The two arranged a deal that allowed Johnson to remain the club’s manager. Madden "used the cotton club as an outlet to sell his #1 beer to the prohibition crowd". When the club closed briefly in 1925 for selling liquor, it soon reopened without interference from the police. Herman Stark then became the stage manager. Harlem producer Leonard Harper directed the first two of three opening night floor shows at the new venue.

The club operated during the United States' era of Prohibition and Jim Crow-era racial segregation. Black People could not initially patronize the Cotton Club, but the venue featured Duke Ellington and many of the most popular black entertainers of the early 20th century. At its prime, it served as a hip meeting spot, with regular "Celebrity Nights" on Sundays. The Cotton Club was a whites-only establishment and reproduced the racist imagery of segregation, often depicting black people as savages in exotic jungles or as "darkies" in the plantation South. The club imposed a subtler color line on the chorus girls, whom the club presented in skimpy outfits.

They were expected to be "tall, tan, and terrific," which meant they had to be at least 5'6" tall, light-skinned, and under 21 years of age. The male dancers' skin colors were more varied. "Black performers did not mix with the club's clientele, and after the show, many of them went next door to the basement of the superintendent at 646 Lenox, where they imbibed corn whiskey, peach brandy, and marijuana." Ellington was expected to write "jungle music" for a white audience; his contributions to the Cotton Club were priceless, as described in this 1937 New York Times excerpt: "So long may the empirical Duke and his music-making rooster's reign and long may the Cotton Club continue to remember that it came down from Harlem."

During the Harlem years, Shows at the Cotton Club were musical revues, and several were called "Cotton Club Parade" following the year. The revues featured dancers, singers, comedians, variety acts, and a house band. The first revue Ellington's orchestra performed was called "Rhythmania" and featured Adelaide Hall. Hall had just recorded several songs with Ellington, including "Creole Love Call," which became a worldwide hit. The club also enabled him to develop his repertoire while composing dance tunes for the shows and overtures, transitions, accompaniments, and "jungle" effects, allowing him the freedom to experiment with orchestral arrangements that touring bands rarely experienced.

Cab Calloway's orchestra brought its "Brown Sugar" revue to the club in 1930, replacing Ellington's orchestra after its departure in 1931. At sixteen, Lena Horne began at the Cotton Club as a chorus girl and sang "Sweeter than Sweet" with Calloway. Dorothy Dandridge performed at the club with her sister Vivian. She was part of the Dandridge Sisters, Tap dancers Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Sammy Davis Jr. (as part of the Will Mastin Trio), and the Nicholas Brothers. After appearing at the Cotton Club, the entire show starring Adelaide Hall was taken out on a road tour across America. Madden's goal for the Cotton Club was to provide "authentic black entertainment to a wealthy, whites-only audience." In June 1935, the Cotton Club opened its doors to black patrons. The club planned a gala to prepare for the Joe Louis fight and "extended an open invitation to the Sepians." The club closed temporarily in 1936 after the race riot in Harlem the previous year. Carl Van Vechten vowed to boycott the club for having such racist policies as refusing entry to blacks.

Langston Hughes, a key figure of the Harlem Renaissance, attended the Cotton Club as a rare Black customer. Following his visit, Hughes criticized the club’s segregated atmosphere and commented that it was "a Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites." In addition to the "jungle music" and plantation-themed interior, Hughes believed that Madden’s idea of "authentic black entertainment" was similar to the entertainment provided at a zoo. That white "strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers - like amusing animals in a zoo." Hughes also believed that the Cotton Club negatively affected the Harlem community. The club brought an "influx of whites toward Harlem after sundown, flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang." Hughes also mentioned how many of the neighboring cabarets, especially black cabarets, were forced to close due to the competition from the Cotton Club. These smaller clubs did not have a large floor or music by famous entertainers like Ellington.

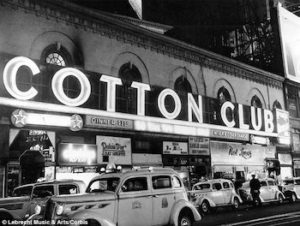

The Cotton Club reopened later that year at Broadway and 48th. The site chosen for the new Cotton Club was a big room on the top floor of a building where Broadway and Seventh Avenue meet, an essential midtown crossroads at the center of the Great White Way, the Broadway Theater District. The Cotton Club closed permanently in 1940 under pressure from higher rents, changing taste, and a federal investigation into tax evasion by Manhattan nightclub owners. The Latin Quarter nightclub opened in its space, and the building was torn down in 1989 to build a hotel.