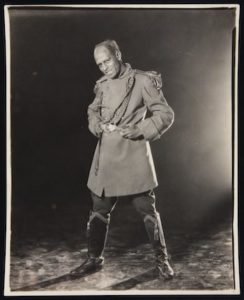

Charles Gilpin

*On this date in 1920, The Emperor Jones held its first performance. It’s a play written by white-American dramatist Eugene O'Neill.

For the first time in mainstream American Theatre, a production featured a full commitment to the principles of the Art Theatre movement. It’s the story of Brutus Jones, a resourceful, self-assured Black (former) Pullman Porter who kills another Black man in a dice game. He is jailed and later escapes to a small, backward Caribbean island, where he sets himself up as emperor. The play recounts his story in flashbacks as Brutus goes through the jungle to escape former subjects who have rebelled against him.

The Emperor Jones broke ground in a second way. It was the first African American actor portrayed as the lead in an American drama. Charles Gilpin brought power and dignity to Brutus Jones, which was new and exciting. When the play begins, he has been Emperor long enough to amass a fortune by imposing heavy taxes on the islanders and carrying on all sorts of large-scale grafts. Rebellion is brewing. The islanders are whipping up their courage to the fighting point by calling on the local gods and demons of the forest.

From the deep of the jungle, they hear the steady beat of a big drum, increasing its tempo towards the end of the play and showing the rebels' presence dreaded by the Emperor. It is the equivalent of the heart-beat which assumes a higher and higher pitch; while coming closer, it denotes the premonition of approaching punishment and the climactic recoil of internal guilt of the Black hero; he wanders and falters in the jungle, present throughout the play with its primeval terror and Blackness.

The play is virtually a monologue for its leading character, Jones, in a Shakespearean range from regal power to the depths of terror and insanity, comparable to Lear or Macbeth. Scenes 2 to 7 are from the point of view of Jones, and no other character speaks. The first and last scenes are a framing device with a character named Smithers, a white trader who appears to be part of illegal activities. In the first scene, an old woman tells Smithers about the rebellion and then has a lengthy conversation with Jones. In the last scene, Smithers converses with Lem, the rebellion's leader. Smithers has mixed feelings about Jones, though he respects Jones more than the rebels. During the final scene, Jones is killed by a silver bullet, which was the only way the rebels believed Jones could be killed, and how Jones planned to kill himself if he was captured.

Originally called The Silver Bullet, the play is one of O'Neill's major experimental works, mixing expressionism and realism and using an unreliable narrator and multiple points of view. It was also an oblique commentary on the U.S. occupation of Haiti after bloody rebellions, an act of imperialism that was much condemned in O'Neill's radical political circles in New York. The Emperor Jones draws on O'Neill's hallucinatory experience of hacking through the jungle while prospecting for gold in Honduras in 1909. The initial Broadway run of The Emperor Jones ran for 204 performances and was followed by an extensive two-year tour of the United States with Gilpin as the lead.

In 1924, when organizing a revival, O’Neill broke with Gilpin over his constant changing of the play’s language. Gilpin insisted that the word “nigger” would not be spoken by a black man, while O’Neill felt it was consistent with the play’s dramatic intent. O’Neill’s replacement for Gilpin was a little-known singer, Paul Robeson. Robeson played Brutus Jones to great reviews in the New York revival and the London production. In 1933, when the play was made into a movie, Robeson, whose star had risen with The Emperor Jones and the musical Showboat, was the choice. The Emperor Jones was O'Neill's first big box-office hit. It established him as a successful playwright after he won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for his first play, the much less well-known Beyond the Horizon (1920). The Emperor Jones was included in Burns Mantle's The Best Plays of 1920–1921.