New Yor Daily Advertiser article

*This date, in 1834, marks the start of the Farren Riot. In New York City, it's also called the anti-abolitionist or Tappan Riot.

This was an anti-abolitionist riot that lasted for nearly a week. Their deeper origins rest in nativism and abolitionism among Protestants who had controlled the growing city since the American Revolutionary War, and fear and resentment of blacks among the ever-increasing underclass of Irish immigrants and their relatives. In 1827, the U.K. repealed legislation controlling and restricting emigration from Ireland, and 20,000 Irish emigrated; by 1835, over 30,000 Irish arrived in New York annually. In May and June 1834, the silk merchants and ardent abolitionists Arthur Tappan and his brother Lewis Tappan stepped up their agitation for the abolition of slavery by underwriting the formation of a female anti-slavery society.

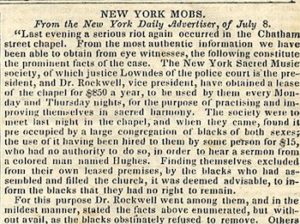

Tappan drew particular attention by sitting in his pew at Laight Street Church with Samuel Cornish, a mixed-race clergyman of his acquaintance. By June, lurid rumors were circulating that abolitionists had told their daughters to marry Blacks, Black dandies in search of white wives were promenading Broadway on horseback, and Arthur Tappan had divorced his wife and married a Black woman. Reports appearing in London in The Times, taken from American newspapers, cite the triggering cause of a disturbance following a misunderstanding at the Chatham Street Chapel.

A former theater converted with money from Tappan for the ministry of Charles Grandison Finney. Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace note that on July 4, an integrated group that had convened at the chapel to celebrate New York's emancipation (in 1827) of its remaining slaves was dispersed by angry spectators. The celebration was rescheduled for July 7. According to The Times, the secretary of the New York Sacred Music Society gave a black congregation permission to use it on July 7 to hold a church service. In this service, members of the society who were unaware of the arrangement arrived and demanded to use the facility. One congregation member called for the chapel to be vacated, but most members refused.

A fight ensued, and constables arrived and arrested six Blacks. Webb's paper described the event as a Negro riot resulting from "Arthur Tappan's mad impertinence." On Wednesday evening, July 9, several thousand whites gathered at the Chatham Street Chapel to break up a planned anti-slavery meeting. When the abolitionists, alerted, did not appear, the crowd broke in and held a counter-meeting, calling for the deportation of blacks to Africa. At the home of Arthur's brother Lewis, his furniture was thrown from windows and set ablaze in the street. Mayor Lawrence arrived but was shouted down, and the police were driven from the scene.

Four thousand rioters descended on the Bowery Theatre to avenge an anti-American remark by George P. Farren, an abolitionist. A production of Metamora was in progress as part of a benefit for Farren. Manager Thomas S. Hamblin and actor Edwin Forrest tried to calm the rioters, who demanded Farren's apology and called for the deportation of Blacks. Violence escalated over the next two days, apparently fueled by inflammatory handbills. A list of other locations slated for the attack included the home of Reverend Joshua Leavitt, the manager of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Tappan's prominently sited Pearl Street store was defended by its staff, armed with muskets. The mob targeted homes, businesses, churches, and other buildings associated with abolitionists and Blacks. The rioting was heaviest in the Five Points area.

The riots quelled when the mayor called out the New York First Division on July 11 to support the police. The "military paraded the streets during the day and the night of the 12th.: they were all furnished with ball cartridge, the magistrates having determined to fire upon the mob, had any fresh attempt been made to renew the riots." At the time, the riots were interpreted by some as just deserts for the abolitionist leaders, who had "taken it upon themselves to regulate public opinion upon slavery" and which showed "smutty tastes" and "temerity." Pro-abolitionist observers saw them as simple explosions of racism.