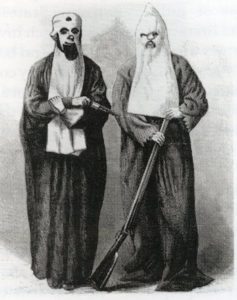

Early Klan Members and their disquises

The founding of the Ku Klux Klan in 1866 is recognized on this date. The Ku Klux Klan is a white-American organization that primarily promotes hatred of all races that are not white and non-protestant religions.

It was organized in Pulaski, TN, in 1865. The original Klan was organized by ex-Confederate elements to oppose the Reconstruction policies of the (then) Republican Congress and to maintain “white supremacy.” After the American Civil War, when the local government in the South was weak, Black anger and insurrection were feared. Informal vigilante organizations and armed patrols were formed in nearly all southern communities. They were linked to societies such as the Men of Justice, the Pale Faces, the Constitutional Union Guards, the White Brotherhood, and the Order of the White Rose.

The Ku Klux Klan was preeminent of these and soon absorbed many of the others. Its strange disguises, silent parades, midnight rides, mysterious language, and commands were found to be most effective in playing upon fears and superstitions. The riders muffled their horses' feet and covered the horses with white robes. They, dressed in flowing white sheets, their faces covered with white masks and skulls at their saddle horns, posed as spirits of the Confederate dead returned from the battlefields. Although the Klan was often able to achieve its aims by terror alone, whippings and lynching were also used, not only against Blacks but also against the so-called carpetbaggers and scalawags.

General Nathan B. Forest, the Confederate cavalry leader, was an early Grand Wizard of the Empire and was assisted by ten Genii. Each state constituted a Realm under a Grand Dragon with eight Hydras as a staff. Several counties formed a Dominion controlled by a Grand Titan and six Furies; a county was a Province ruled by a Grand Giant and four Night Hawks. A Grand Cyclops with two Night Hawks as aides governed the local Den. The individual members were called Ghouls.

Initially, the Klan was not completely victorious in overthrowing Radical Republican rule. Its efforts were too utterly criminal and occurred when Northern opinion still supported a systematic radical policy toward the South. In three "enforcement acts," Congress moved to outlaw the Klan and other vigilante organizations. The first of these measures was the Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870. Designed to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment, it provided heavy penalties of fines and imprisonment if anyone by force, bribery, or intimidation hindered or prevented citizens from voting.

The Klan was effective in systematically keeping Black men away from the polls so that the ex-Confederates gained political control in many states. William J. Simmons, an ex-minister and promoter of fraternal orders, founded the second Ku Klux Klan in 1915; its first meeting was held in Stone Mountain, GA. The new Klan had a wider program, adding “white supremacy,” an intense anti-Catholicism, and an anti-Semitic platform closely related to the Know-Nothing movement of the middle 19th century. As a result, its appeal spread rapidly throughout the North. It was an outlet for the militant patriotism stirred up by World War I, stressing fundamentalism in religion. Although it was nonpolitical, the Klan still controlled politics in many communities.

It elected many state officials and Congressmen in 1922, 1924, and 1926. Texas, Oklahoma, Indiana, Oregon, and Maine were under its influence. Its power in the Midwest was broken when David C. Stephenson, a prominent Klan leader, was convicted of second-degree murder. Proof of corruption led to the indictment of the governor of Indiana and the mayor of Indianapolis, both Klan supporters. The Klan frequently took extreme extralegal measures, especially against those whom it considered its enemies. At its peak in the mid-1920s, its membership was estimated at 4 million to 5 million. Though probably much smaller, the Klan declined with amazing speed to an estimated 30,000 by 1930.

The Klan spirit, however, was a factor in breaking the Democratic hold on the South in 1928, when Alfred E. Smith, a Roman Catholic, was that party's presidential candidate. Its collapse was primarily due to state laws against masks eliminating the secret aspect, the bad publicity the organization received through its thugs and swindlers, and maybe from a declining interest. With the Depression, the dues-paying membership of the Klan shrank to almost nothing. Meanwhile, many of its leaders had done extremely well financially from the dues and the sale of Klan paraphernalia. This trend continued during the Second World War, and in 1944, the organization was disbanded.

In The 1950s, the re-emergence of the American Civil Rights Movement resulted in a revival of Ku Klux Klan organizations. The most important of these was the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, led by Robert Shelton. In the Deep South, considerable pressure was again put on Blacks by Klansmen not to vote. An example of this was the state of Mississippi. By 1960, 42% of the population was Black, but only 2% were registered to vote. In 1947, the first Freedom Ride was employed for Black voting registration. Lynching was still employed as a method of terrorizing the local Black population. On September 15, 1963, Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was bombed, and the explosion killed Denise McNair (11), Addie Mae Collins (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Cynthia Wesley (14). A witness identified Robert Chambliss, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, as the man who placed the bomb under the steps of the church. On October 8, 1963, Chambliss was found not guilty of murder and received a $100 fine and a six-month jail sentence for having the dynamite.

In 1964, the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized its Freedom Summer campaign. Freedom Schools were often targets of white mobs, which included the Ku Klux Klan. The homes of local Blacks were also involved in the campaign. That summer, 30 Black homes and 37 Black churches were firebombed. White mobs, racist police officers, and the Klan beat over 80 volunteers. The Ku Klux Klan murdered three men, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, on June 21, 1964. The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing was unsolved until 1977. Chambliss was tried again, found guilty, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

In 1981, the trial of Josephus Anderson, a Black man charged with the murder of a white policeman, took place in Mobile and ended with the jury unable to reach a verdict. This upset the local Ku Klux Klan, who thought the hung jury resulted from blacks on the jury. After the trial, Bennie Hays, the second-highest-ranking official in the Klan in Alabama, said: "If a Black man can get away with killing a White man, we ought to be able to get away with killing a Black man."

On March 21, 1981, Hay’s son, Henry, and James Knowles traveled around Mobile in their car until they found 19-year-old Michael Donald walking home. They forced him into their car and took him to the next county, where he was lynched. A brief investigation by the local police claimed that the murder resulted from a disagreement over a drug deal. Jessie Jackson came to Mobile and led a protest march about the failed police investigation, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) looked into the case. In June 1983, Knowles was found guilty of violating Donald's civil rights and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Six months later, Henry Hays was tried for murder, found guilty, and sentenced to death. With the support of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), this case was used to try to destroy the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama. Donald’s mother brought a civil suit against the United Klan of America, which took place in February 1987. The all-white jury found the Klan responsible for the lynching of Michael Donald and ordered it to pay $7 million. The Klan had to hand over all its assets, including its national headquarters in Tuscaloosa. Henry Hayes was executed in 1997, the first time a white man had been executed for a crime against a Black since 1913.

In 1999, a discovered 54-year-old letter prompted Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia to reveal a part of his past he says he’d rather forget. Byrd said his membership in the Ku Klux Klan as a young man has "emerged throughout my life to haunt and embarrass me and has taught me, in a very graphic way, what one major mistake can do to one’s conscience, career and reputation." Byrd’s membership in the Klan, an issue in his first campaign for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1952, was raised in the book When Jim Crow Met John Bull, published by St. Martin’s Press, written by Graham Smith.

Although a resurgence of support for the Klan was manifest in the surprising popularity in the early 1990s of David Duke of Louisiana, actual membership in Klan organizations was estimated to be in the low thousands. In May 2000, the FBI announced that the Ku Klux Klan splinter group, the Cahaba Boys, had carried out the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing. It was claimed that four men, Robert Chambliss, Herman Cash, Thomas Blanton, and Bobby Cherry, had been responsible for the crime. Cash was dead, but Blanton and Cherry were arrested. Two years later, 71-year-old Bobby Cherry was convicted of the murder of the four children and was sentenced to life in prison.

In 2003, the Supreme Court upheld a 50-year-old Virginia law that makes cross-burning an act of intimidation. This was over an incident where Richard Elliot and Jonathan O’Mera were convicted of burning a 4-foot cross on the lawn of their neighbors, the Jubilee family, a mixed couple. In 2017, they participated in the white supremacy rally and protest in Charlottesville, Virginia, where a white woman was killed.

The modern Klan is not one organization but composed of small independent chapters across the United States. In 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which monitors extremist groups, estimated that there were "at least 29 separate, rival Klan groups currently active in the United States, and they compete with one another for members, dues, news media attention and the title of being the true heir to the Ku Klux Klan". The formation of independent chapters has made Klan groups more difficult to infiltrate, and researchers find it hard to estimate their numbers. Analysts believe about two-thirds of Ku Klux Klan members are concentrated in the Southern United States, with another third primarily in the lower Midwest.

Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and

African American Experience

Editors: Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Copyright 1999

ISBN 0-465-0071-1