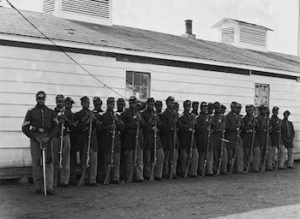

The first Colored TroopsLouisiana Native Guards

On this date in 1863, in North Carolina, the United States War Department established the Bureau of Colored Troops to support the Union Army in the American Civil War. Regiments of colored troops from all nation-states were reorganized into what became known as the United States Colored Troops (USCT).

Blacks have a rich history in the United States military, even before this official act of inclusion. This was one of the first authorized attempts by the Federal government to enlist former slaves in defense of the Union. The policy was innovative, new, and controversial, with varying degrees of success. The differences in how Blacks were recruited and their responses to Union policy depended greatly on local conditions, the relationship between widely divergent personalities, and the recent regional experiences of the Black population.

The project designers were among the nation's most sympathetic supporters of Black service preceding the formation of the 54th Infantry commanded by General Robert G. Shaw. All the same, too many officers cared too little about how they promoted Black recruits. All too common was the 3rd South Carolina Colored Infantry's betrayal over the unequal pay issue, its difficult fatigue duties, and the number of incompetent regimental officers who faced dismissal or military charges. By the war's end, Black recruitment would become widely accepted, and South Carolina would provide just over 5,000 of the 179,000 Black troops raised.

Although several regiments fought bravely and heroically and won some of the country's highest honors for their courage and service, Black troops suffered more than white troops. Their conditions were harsher than those of white soldiers because they were of lesser status. Black troops suffered diseases such as measles, smallpox, and rheumatism in greater numbers than their fellow Union soldiers.

Adding to the lore of the USCT was the presence of prominent figures in African American culture. Martin Robinson Delany, the abolitionist, Black Nationalist, and a compatriot of Frederick Douglass, was the highest-ranking Black staff officer to serve in the federal army during the Civil War. Douglass' sons served in a USCT regiment.

By no means were Blacks welcomed by all of their white northern comrades. Many whites in the north were outraged that Blacks, especially ex-slaves, were now wearing the uniform of “their” country. This attitude, along with the alleged order by Confederate President Jefferson Davis that no Black soldiers or white officers leading Black soldiers should be taken prisoner, made military life extremely difficult. Still, the men were determined to fight and preserve their freedom at all costs. This view was derived from President Davis’ proclamation branding Generals Hunter and Phelps as outlaws and the soldiers under General Butler's command as robbers and criminals deserving of death.

Before going into battle, Black troops were warned by their commanders that they would not be taken prisoner if they were forced to surrender, so they knew that they had to fight until death. After the Fort Pillow, Tennessee, and Poison Springs, Arkansas, massacres of April 1864, the Colored Troops adopted the battle cries, “Remember Fort Pillow” and “Remember Poison Springs.” According to the research, black soldiers were taken prisoner, but just how they were treated is unknown. Between 160 and 170, regiments of Infantry, cavalry, heavy artillery, and batteries of light artillery were organized. The exact number is difficult to determine because of the early reorganization in the recruiting cycle and the resulting redesignations.

In addition, some units were deactivated or consolidated. Depending on the data sources, the total number of enlistees varies from 176,000 to over 200,000. The compiled index lists approximately 178,000 names. Approximately 135,000 were recruited from the states that seceded and the border slave states. States furnishing the most significant numbers were Louisiana (24,052), Kentucky (23,703), Tennessee (20,133), and Mississippi (17,869). There were over 7,000 white officers. Omitted from these numbers are the 100,000 to 200,000 civilians who served in numerous capacities with the U.S. Colored Troops and in all-white units as scouts, spies, cooks, corpsmen, nurses, teamsters, and various other positions. Very few records were maintained on these individuals except in the personal papers of the officers. There were no organized Black units at Gettysburg or any other significant battles, so prominently published.

In many of those battles, there were probably more Black soldiers serving with the Confederates as body servants, teamsters, and so on than in the Union forces. Before July 1, 1863, and the Battle of Gettysburg, Black soldiers engaged the enemy in numerous battles and major skirmishes throughout the South. The most intense engagements occurred in Louisiana at Port Hudson and Milliken’s Bend. The United States Colored Troops participated in 449 encounters in the Civil War, of which 39 were major battles. The most active units in the South and West were the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry (79th USCI), 14 battles, and the 1st Mississippi Cavalry (3rd USCC), ten battles.

Three regiments participated in the Battle of Olustee, Florida, on February 20, 1864, in which the Union forces were defeated. Hundreds of lives were lost, and many were captured and sent to the Andersonville, Georgia, prison. Nine regiments participated in the Battle of Fort Blakely, Alabama, from March 31 to April 9, 1865. In Virginia, 22 regiments participated in the Siege of Petersburg. One cavalry and twelve infantry regiments fought at Chapin’s Farm outside Richmond on September 29 and 30, 1864. Thirteen U.S. Colored Troops were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Library of Congress

101 Independence Avenue S.E.

Washington D.C. 20540