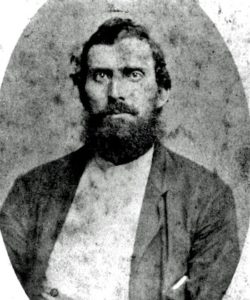

Newton Knight

*Newton Knight ion was born on this date in 1837. He was a white-American abolitionist, farmer, unionist, and Confederate soldier.

Knight was born near the Leaf River in Jones County, Mississippi, a region dominated by virgin longleaf pines, and wolves and panthers roamed the land. Knight married Serena Turner in 1858, and they moved to the edge of Jasper County to set up a homestead where they grew corn and sweet potatoes and raised hogs and cattle. Fruits, berries, and wild game added variety to their diets. He tilled the land himself. According to his son, Knight never drank or cursed, was a Primitive Baptist, and doted on his children.

He would become a man of myth and legend. Soon after the election of Abraham Lincoln as United States president in November 1860, slave-owning planters led Mississippi to join South Carolina and secede from the Union in February 1861. Other southern states would follow suit. Mississippi’s Declaration of Secession reflected the planters’ interests in the first sentence: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery.” However, many yeoman farmers and cattle herders of Jones County had little use for a war over a “state’s right” to maintain the institution of slavery. By 1860, slaves made up only 12 percent of the total population in Jones County, the smallest percentage of any county in the state.

Jones County elected John H. Powell, the "cooperation" (anti-secession) candidate, to represent them at Mississippi's secession convention in January 1861. Under pressure, Powell voted against secession on the first ballot but switched his vote on the second ballot, joining the majority of whites in voting to secede from the Union. In an interview many years later, Knight suggested that many Jones County voters, not understanding Powell's limited choices, felt betrayed by his action. The American Civil War began in May of 1861. Knight joined the Confederate army in July 1861, enlisting in the 8th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. Six months later, he was given a leave to return home and tend to his ailing father.

In May 1862, Knight and several friends and neighbors enlisted in Company F of the 7th Mississippi Infantry Battalion. They preferred to serve together in the same company rather than with strangers. The men of Jones County and the region were disturbed by news from home reporting the poor conditions, as their wives and children found it hard to keep up the farms. Knight was enraged when he received word that Confederate authorities had seized his family's horses for their use. However, many believe Knight's principal reason for desertion was his anger over the Confederate government's passing of the Twenty Negro Law. This act allowed large plantation owners to avoid military service if they owned 20 slaves or more.

Knight had taken to the swamp on the Leaf River to evade authorities, finding other deserters and fugitive slaves there. He and his followers organized the Knight Company on October 13, 1863. It was a band of guerrillas from Jones County and adjacent counties of Jasper, Covington, Perry, and Smith, who intended to protect the families and farms from Confederate authorities, including high takings of goods for taxes. Knight was elected "captain" of the company, which included many of his relatives and neighbors. The company's main hideout, "Devils Den," was located along the Leaf River at the Jones-Covington county line. Local women and slaves provided food and other aid to the men. Women blew cattle horns to signal the approach of Confederate authorities to their farms.

By the mid-1870s, Knight had separated from his wife, Serena. He married Rachel, a Black freedwoman formerly held as a slave by his grandfather. Knight's grown son, Mat (from his first wife), married Rachel's grown daughter, Fannie, from a previous union. Knight's daughter, Molly, married Rachel's son, Jeff, making three interracial families in the community. Newton and Rachel Knight had several children before she died in 1889. Newton Knight died on February 16, 1922, at 92. Despite a Mississippi law that barred the interment of whites and blacks in the same cemetery, he was buried at his request in what is now called the Knight Family Cemetery, next to Rachel on a hill in Jones County overlooking their farm. Newton's engraved epitaph read, "He lived for others."