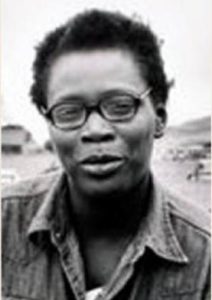

Pat Parker

*Pat Parker was born on this date in 1944. She was a Black lesbian women’s advocate, author, and poet.

Southern born and educated in Houston, Texas, Pat Cooks was the youngest of four daughters in a Black working-class family. Her parents were Marie Louise (née Anderson) and Ernest Nathaniel Cooks. Marie Louise worked as a domestic worker, and Ernest retreaded tires. She was the youngest of four daughters. The family lived first in the Third Ward and then moved to the Sunnyside neighborhood when Parker was four. Urged by her father to take "the freedom train of education,"

Parker later immigrated to Oakland, California, in the early 1970s to pursue work, writing, and activism opportunities. From 1978 to 1987, she worked as a medical coordinator at the Oakland Feminist Women's Health Center, which grew from one clinic to six sites. Parker’s political activism ranged from involvement with the Black Panther Party and Black Women's Revolutionary Council to forming the Women's Press Collective to wide-ranging activism in gay and lesbian organizations.

She held positions of national leadership regarding women's health issues, especially concerning domestic and sexual violence. From all these stages of her life, Parker developed narrative poetry, often taking on a call and response to Black and working-class oral traditions and often speaking of generations of women and men engaged in human rights battles. Parker's poetry generally escaped didacticism because of her deft use of humor, insistence on frank language, events presentations, long silent images, and sharp analysis of injustices. The goal, Parker said in an interview with Kate Rushin, is to "try to put the poetry in the language that we speak, to use that language, take those simple works and make out of them something that is moving, that is powerful, that is there."

Parker gave the first public reading of her poetry in 1963 while married to playwright Ed Bullins. The challenge of "competing in a male poetry scene" as the wife of a writer, Parker noted, helped develop not only her voice but also her willingness to write about contemporary issues -- about civil rights and Vietnam as well as an emerging Black lesbian feminist perspective on love and lust. Parker and Bullins separated after four years. She later said that her ex-husband was physically violent and that she was "scared to death." She married Robert F. Parker, writer, and publisher, but decided that the "idea of marriage... wasn't working" for her. She began to identify as a lesbian in the late 1960s and, in a 1975 interview with Anita Cornwell, stated: "After my first relationship with a woman, I knew where I was going."

Reading before women's groups beginning in 1968 brought Parker notice and satisfaction, but also intermixing poetry with musical performances at local women's bars, coffeehouses, and festivals. "It was like pioneering," Parker said to Rushin. "We'd go into these places and stand up to read poems. We were talking to women about women and, at the same time, letting women know that the experiences they were having we shared by other people ... I was being gay, and it made absolute sense to me that that was what I had to write about."

Parker and Audre Lorde first met in 1969 and became close friends. They continued to exchange letters and visits for twenty years until Parker’s death twenty years later. Parker’s published works include “Child of Myself” (1972), “Pit Stop” (1973), “Womanslaughter” (1978), “Movement in Black” (1978), and “Jonestown & Other Madness (1989). In 1978, selections from “Child of Myself” and “Pit Stop” were included in “Movement in Black: The Collected Poetry of Pat Parker, 1961–1978.” She has also appeared in numerous anthologies, magazines, and newspapers. Critics like Barbara Smith and Cheryl Clarke agree that Parker's poems were designed to be spoken, to confront both Black and women's communities with, as Clarke notes, "the precariousness of being non-white, non-male, non-heterosexual in a racist, misogynist, homophobic, imperial culture."

Parker's five collections of poetry take their central images and process of self-creation and political analysis from autobiographical moments in Parker's life and publicized incidents or community discussions related to race, class, gender, and sexuality. Her Jonestown and Other Madness poems consider what isn't -- what love isn't, what liberation isn't, what justice isn't, and what is -- love and alliances, family legacies, and strength. This last collection, published before Parker's death on June 17, 1989, from breast cancer, ends with a desire for more time to write and a legacy to her daughters. These are the legacies Parker passes on to her daughters and her many public readers. At her death, her long-time partner Marty Dunham and two daughters, Cassidy Brown and Anastasia Dunham Parker, survived Pat Parker.