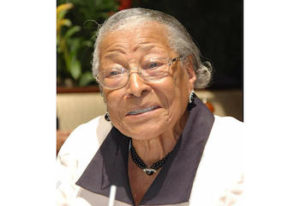

Recy Taylor

*Recy Taylor was born on this date in 1919. She was a Black activist for racial justice and women’s rights and a defendant in a high-profile rape case.

From Abbeville in Henry County, Alabama, Taylor was one of four siblings, a brother and two sisters. On September 3, 1944, Taylor was walking home from Rock Hill Holiness Church in Abbeville with her friend Fannie Daniel and Daniel's teenage son West when a car pulled up on the side of the road. In the car were white US Army Private Herbert Lovett and six other white men, all armed. Herbert Lovett accused Taylor of cutting “that white boy in Clopton this evening.” This accusation was false, as Taylor had been with Daniel all day. The seven men forced Taylor into the car at gunpoint and proceeded to drive her to a patch of trees on the side of the road. She was raped by six of the men, including Lovett.

Taylor's kidnapping was reported immediately to the police by Daniel. She identified the car as belonging to Hugo Wilson, who pinned the rape on six men, Dillard York, Billy Howerton, Herbert Lovett, Luther Lee, Joe Culpepper, and Robert Gamble. Even though three eyewitnesses identified Wilson as the driver of the car, the police did not call in any of the men Wilson named as assailants, and Wilson was fined $250. The black community of Abbeville reported to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Montgomery, Alabama, who sent down Rosa Parks.

Parks took the case back to Montgomery, where she started to form a defense for Taylor with the assistance of E.D. Nixon, Rufus A. Lewis, and E. G. Jackson, all influential men in the Montgomery community. The group recruited supporters across the entire country. The trial occurred on October 3 and 4, 1944, with an all-white, all-male jury. None of the assailants had been arrested, meaning the only witnesses were Taylor's friends and family. Taylor's family could not identify the assailants with just names since the Sheriff never arranged a police line-up. Taylor could not identify her attackers in court. After five minutes of deliberation, the jury dismissed the case. The only way it could be re-opened would be through an indictment from the grand jury.

Taylor received death threats in the months following the trial, and white supremacists firebombed her home. Taylor and her husband and child moved into the family home, where her father and siblings would help protect Taylor. Benny Corbitt took guard in a tree every night with a gun guarding Taylor and her family until daybreak. Talk of "the rape and phony hearing" resonated through NAACP chapters throughout the South and within Black communities. The activists convened at the Negro Masonic Temple in Birmingham, Alabama, where members of the Montgomery and Birmingham NAACP, editors and reporters from the Alabama Tribune and Birmingham World, and members of the Southern Negro Youth Congress, or SNYC, amongst others, coordinated efforts to bring justice for Taylor.

SNYC members, Rosa Parks, and other primarily female activists helped spread Recy Taylor's story. Accounts were printed in the Pittsburgh Courier, the New York Daily News, and the Chicago Defender. The group included W.E.B. Du Bois, Mary Church Terrell, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, and Langston Hughes. The group drew the attention of the FBI as the House Un-American Activities Committee argued that the group was simply a cover for the Communist Party. After various other newspaper publications and widespread knowledge of the attack, black activists started writing to the then Governor of Alabama, Chauncey Sparks, who reluctantly agreed to launch an investigation.

After Sparks launched an investigation, Sheriff Gamble was interviewed again about his measures to ensure justice on behalf of Taylor. Gamble falsely claimed that he started an investigation of his own immediately after the attack. He also claimed that he had arrested all of the men involved in the rape two days after the assault and that he had placed Hugo Wilson, the man identified as the owner of the car, under a $500 bond. He also accused Taylor of being "nothing but a whore around Abbeville" and that she had been "treated for some time by the Health Officer of Henry County for venereal disease." Later, other white men from Abbeville identified Taylor as an "upstanding, respectable woman who abided by the town's racial and sexual mores."

Investigators interviewed the rapists, and four of the seven men "admitted to having intercourse with Taylor, Joe Culpepper, admitted that he and the other rapists were out looking for a woman the night of the attack, that Lovett got out of the car with a gun and spoke to Taylor, that Taylor was forced into the car and later forced out of the car and made to undress at gunpoint, was raped and later blindfolded and left on the side of the road. Culpepper's retelling of the story directly aligned with Taylor's original account. However, even with this information, including several of the alleged assailants’ testimonies, the attorney general "failed to convince the jurors of Henry County that there was enough evidence to indict the seven suspects when he presented Taylor's case on February 14, 1945." The second all-white male jury refused to issue any indictments.

The Black community was shocked at the second dismissal of Taylor's case. Despite the outcome, the case strengthened the 20th-century American Civil Rights movement and mobilization of activists nationwide. Taylor lived in Abbeville with her family for two decades after the attack. She said that during those years, she lived "in fear, and many white people in the town continued to mistreat her, even after her attackers left." She eventually moved to Florida.

On Mother's Day in 2011, the Alabama House of Representatives apologized to Taylor on behalf of the state "for its failure to prosecute her attackers." State Representative Dexter Grimsley, Abbeville Mayor Ryan Blalock, and Henry County Probate Judge JoAnn Smith also apologized to Taylor for her treatment. Taylor received the apologies when she visited Rock Hill Holiness Church in Abbeville, where she was kidnapped. "I felt good," she said. "That was a good day to present it to me. I wasn't expecting that." In 2011, Taylor visited the White House and attended a forum on Rosa Parks at the National Press Club. A 2017 documentary about the case was shown at the New York Film Festival. Recy Taylor died in her sleep at a nursing home in Abbeville, Alabama, on December 28, 2017, aged 97.