On this date in 1955, the Supreme Court ruled against Atlanta's "separate but equal" precept in public golf courses.

The case was called Holmes vs. Atlanta. The Holmes family was prominent in post-war Atlanta. Dr. Hamilton M. Holmes, Sr., conducted his family practice out of an office on Auburn Ave. in the city's heart. His son, Oliver Wendell Holmes, was a well-respected minister. Alfred (Tup) Holmes was the outspoken sibling; he served as union steward at Lockheed Aircraft in Marietta, Georgia, in 1951, when the Holmes trio joined Charles T. Bell to make a stand against segregation.

This foursome shared a passion for golf and, like most of Atlanta's Black elite, they all belonged to Black-owned and Black-run Lincoln Country Club, a nine-hole layout better known for the quality of its buffet than its course conditions. The group attempted to play at a course on the other side of town. Although Bobby Jones Golf Course, located on the affluent northwest side of town, was one of seven public venues within the city limits, it was off-limits to Blacks unless they carried someone else's clubs. Sensing resistance, Tup and Bell devised a plan to help persuade the others. They would dispatch ahead one of their members, K.B. Hill, who passed for white on several deceptions, to infiltrate the whites-only course.

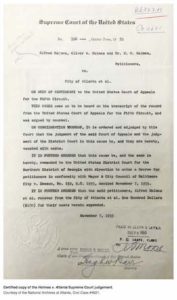

However, the racism with which the group was confronted on that mid-summer morning was no laughing matter. "The head pro told us straight out we couldn't play, that they didn't allow no niggers at Bobby Jones," recalled Bell. Hill was quickly corralled and escorted off the grounds along with the others. It took two years, but they eventually filed a lawsuit--Holmes vs. Atlanta--that sought to desegregate public golf courses and parks in the city. Dissatisfied with U.S. District Court Judge Boyd Sloan's 1954 ruling, the litigants appealed to a higher court.

John H. Calhoun, a businessman and president of the local chapter of the NAACP, recommended the organization throw its clout behind the golfers. The NAACP responded by providing resources and the chief counsel of its LDF, legal defense team, and a lawyer named Thurgood Marshall to present their case before an appeals court in New Orleans. When that court upheld Judge Sloan's ruling, the golfers were forced to take their fight to the nation's ultimate battleground, the U.S. Supreme Court. This time, they won. The Supreme Court accepted the case in the fall term of 1955 and ruled in favor of the black golfers.

Not everyone was happy with this outcome, especially Georgia Gov. Marvin Griffin, who had added to an already incendiary climate by declaring, "Co-mingling of the races in Georgia state parks and recreation areas will not be tolerated." Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield urged the city to sell its courses to individuals, who could then declare them open to private members only. Although Hartsfield's effort failed, it fueled the growing anger of diehard Jim Crow preservationists.

Atlanta's public courses, however, were officially desegregated without incident. "It's gratifying to know that I participated in something so meaningful," said Bell, the only survivor of the original foursome.

Dr. Holmes died in September 1965, Oliver nearly a year to the day later, and Tup succumbed to cancer in December 1967. In 1983, Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young renamed Adams Park Golf Course the Alfred E (Tup) Holmes Memorial GC. Fittingly, the city maintained it for the enjoyment of all its citizens until 1986, when it was leased to the American Golf Management Company.

Historic U.S. Cases 1690-1993:

An Encyclopedia New York

Copyright 1992 Garland Publishing, New York

ISBN 0-8240-4430-4