On this date, we celebrate the Black African customs regarding cemeteries and funerals preserved through American slavery. One of the most direct and unaltered visual manifestations of African influence on the culture of Blacks in the United States is found in the social behaviors centered on funerals.

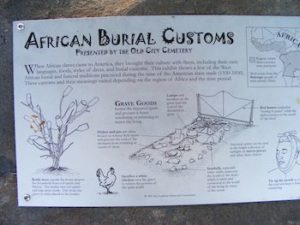

In many American rural graveyards across the South and many urban cemeteries in the North and far West, too, blacks mark the final resting places of loved ones distinctively. While standard markers or floral arrangements are typically used, the deceased's personal belongings are often placed on the grave. This can range from a single emblematic item, like a pitcher or vase, to an inventory of the dead person’s household goods. One can find clocks, cups, saucers, toothbrushes, marbles, piggy banks, and many other items.

Such material collections of honor contrast with the typical contemporary white American ideal of a burial landscape. They establish a connection to customs and practices known not only on southern plantations but also in West and Central Africa.

Black graves in Georgia were always decorated with the last article used by the departed, according to Documents from 1843. Historians traveling throughout Zaire in 1884 noted that natives mark the final resting places of their friends by decorating graves with such items as old cooking pots, which were made useless by penetrating them with holes. Another traveler in nearby Gabon observed that over or near the graves of the rich are built small huts, where mourners laid the common articles used in their lives; pieces of cooking, knives, and sometimes a table.

In early American slavery, funeral customs were among the few areas of Black life where slave owners tended not to intrude. Despite the massive conversion of Africans to Christianity, they retained many of their former rituals associated with the respect of the dead. Placing personal items on graves is more than an emotional gesture. One resident of the Georgia Sea Islands testified, “Spirits need these [things] same as the man. Then the spirit rests and don’t wander.” In addition to personal objects, some Black graves in the South are decorated with white seashells and pebbles, suggesting the watery environment at the bottom of the ocean, lake, or river.

Such material items are not associated with the Christian belief in salvation; they are more likely signs of a remembrance of African customs. In South Carolina, nearly 40 percent of all slaves imported between 1733 and 1807 were from the Kongo-speaking region; their world of the dead is known to be underground yet underwater. This place is the realm of the Bakula, creatures whose white color marks them as deceased. Shells and stones signal the boundary of this realm, which can only be reached by penetrating beneath the two physical barriers. Their whiteness remembers that white, not black, in Central Africa is the color of death.

Also found in Black cemeteries are pipes driven into burial mounds to serve as speaking tubes that may allow communication with the deceased and mirrors that are said to catch the flashing light of the spirit and hold it there. These same customs are found in the Bay Area of California burial sites. When given the opportunity, anyone will carry a heartfelt custom and tradition from place to place as essential cultural property.

An Encyclopedia of African American Christian Heritage

by Marvin Andrew McMickle

Judson Press, Copyright 2002

ISBN 0-817014-02-0