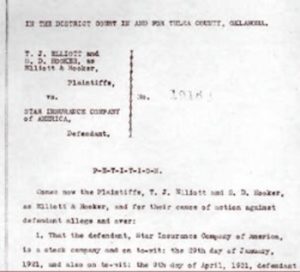

Petition (copy)

*On this date in 1921, Lockard v. Evans et al. was filed in Tulsa County District Court, Oklahoma. This was legal action from a group of Blacks against the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma, to rebuild their neighborhoods destroyed by the Tulsa Race Massacre earlier that summer.

As Tulsans began to shift the rubble after the riot, they asked themselves how such a tragedy had occurred, who was to blame, and how they might rebuild. The Tulsa County District Court filing was Case #15,780 Lockard v. Evans. A three-judge panel upheld the suit prohibiting the building of permanent structures while allowing the building of temporary structures. The Black property owners argued that the city was depriving them of their homes by such limited building regulations and that the restrictions endangered their health. Their argument was partly based on the emerging police power doctrine that the state could regulate to promote health and morality. The petitioners applied a consequence to that principle, arguing that the city was prohibited from interfering with that protection.

The judges first granted a temporary restraining order against the ordinance in August because there was insufficient notice when it was passed. Then, following the re-promulgation of the ordinance, the judges granted a permanent injunction against it, citing the ordinance's effect on property rights. The judges' opinion has since been lost. Briefly looking at the sequence of events soon after the riot happened, a grand jury investigated the riot's causes and returned indictments against about seventy men, mostly Blacks. The city re-zoned the burned district to discourage rebuilding, as Greenwood residents and property owners (both black and white) filed more than one- hundred suits against their insurance companies, the city of Tulsa, and even Sinclair Oil Company, which allegedly provided airplanes that were used in attacking Greenwood. Not one of those suits was successful.

One, filed by William Redfearn, a white man who owned a hotel and a movie theater in Greenwood, went to trial and then on appeal to the Oklahoma Supreme Court. Redfearn's insurance company denied liability, citing a riot exclusion clause. The clause exempted the insurance company from liability for loss due to riot. The Oklahoma Supreme Court interpreted the damage as due to a riot-an understandable conclusion, and thereby immunized insurance companies from liability. Following the failure of Redfearn's suit, none other went to trial. Just as the legal system had failed to provide a vehicle for recovery by Greenwood residents and property owners, the legal system failed to hold Tulsans criminally responsible for the reign of terror during the massacre.

The grand jury, convened a few days after the riot, returned about seventy indictments. A few people, mostly Blacks, were held in jail. Others were released on bond, pending their trials for rioting. However, most of the cases were dismissed in September 1921; when Sarah Page failed to appear as the complaining witness, the district attorney dismissed Dick Rowland's case was dismissed. Other dismissals soon followed. Apparently, no one, black or white, served time in prison for murder, larceny, or arson, although some people may have been held in custody pending the dismissal of suits in the fall of 1921.

Perhaps the grand jury's most notable action was not the indictments it returned but the whitewash or hiding of it they engaged in. Their report, published in the Tulsa World under the heading "Grand Jury Blames Negroes for Inciting Race Rioting: Whites Clearly Exonerated," told a laughable story of Black culpability for the riot. The report demonstrated how evidence could be selectively interpreted. It is, quite simply, a classic case of an interpreter's extreme biases coloring their vision of events. The grand jury began work on June 7, taking testimony from dozens of White and Black Tulsans. It operated within the framework established by Tulsa District Judge Biddson, instructing the jurors to investigate the riot's causes. Biddson feared that the spirit of lawlessness was growing.

The jurors' conclusions would be "marked indelibly upon the public mind" and would be important in deterring future riots. It cast its net widely, looking at the riot unfolding and Tulsa's more general social conditions. The grand jury fixed the immediate cause of the riot as the appearance "of a certain group of colored men who appeared at the courthouse for the purpose of protecting Dick Rowland." From there, it blamed those who sought to defend Rowland's life. It discounted rumors of lynching. "There was no mob spirit among the whites, no talk of lynching, and no arms." Echoing the discussions of the riot in the white Tulsa newspapers, the grand jury identified two remote causes of the riot, which were "vital to the public interest." Those causes were the "agitation among the Negroes of social equality" and the breakdown of law enforcement.

The agitation for social equality was the first of the remote causes the jury discussed: Certain propaganda and more or less agitation had been going on among the colored population for some time. This agitation resulted in the gathering of firearms among the people and the storage of quantities of ammunition, all of which was accumulated in the minds of the Negro, which led them as a people to believe in equal rights, social equality, and their ability to demand the same. The Nation broke the grand jury's code. Charges that Blacks were radicals meant that Blacks were insufficiently submissive. They asked for legal rights. Negroes were openly denouncing Jim Crow cars, lynching, and peonage; in short, they were asking that the Federal constitutional guarantees of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" be given regardless of color.

The Negroes of Tulsa and other Oklahoma cities were pioneers; men and women who had dared, men and women who had the initiative and the courage to pull up stakes in other less-favored states and face hardship in a newer one for the sake of greater eventual progress. Those whites who sought to maintain the old white group control naturally did not relish seeing Negroes emancipating themselves from the old system. Such was the mindset of the grand jury that they thought ideas about racial equality were to blame for the riot instead of explaining why Greenwood residents felt it necessary to visit the courthouse. Thus, the grand jury recast its evidence to fit its established prejudices.

And as it did that, as it confirmed white Tulsa's myth that the Blacks were to blame for the riot, it helped to remove the moral impetus to reparations. Given the environment of racial violence and segregation legislation of Progressive-era Oklahoma, it makes sense that one of the city government's first responses was to expand the fire ordinance to incorporate parts of Greenwood. That expansion made rebuilding in the burned district prohibitively expensive. The city presented two rationales: to expand the industrial area around the railroad yard and to separate the races further.

The story of the zoning ordinance was one of the few triumphs of the rule of law to emerge from the riot. Greenwood residents who wanted to rebuild challenged the ordinance as a violation of property rights on technical grounds. They first won a temporary restraining order on technical grounds (that there had been insufficient notice before the ordinance was passed).

Then, following the re-promulgation of the ordinance, they won a permanent injunction, apparently because it would deprive the Greenwood property owners of their property rights if they were not permitted to rebuild. Having won one court victory, Greenwood residents were left to their own devices: free to rebuild their property, but without the direct assistance from the city that was crucial to doing so. Now, the question is whether the city and state wish to acknowledge that as a debt and to pay it.