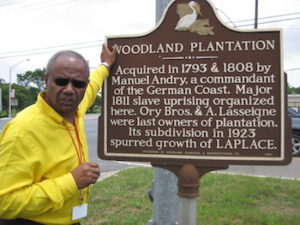

Commemorative Plaque

On this date in 1811, Black slaves rebelled against their white masters in Louisiana.

Often called the German Coast Uprising, Charles Deslondes and other slaves began the revolt on the plantation of Manual Andry. The Deslondes plantation surrounded the Andry plantation. Charles was a field laborer on the Deslondes plantation where he was born. At the time of the revolt, he was about 31 years old. The Andry plantation was the site of an arsenal for the local Militia. On the night of January 8, it began to rain, but the rebels stuck to their plans; they began by overwhelming Gilbert Andry and his son. After discovering that the arsenal had been removed, they killed Andry’s son. Colonel Andry was sparred.

Armed with cane knives, hoses, clubs, and a few guns, the rebels began the march down River Road towards New Orleans. They were motivated by the French slogan "Sur la Orleans," as only three slaves out of the 141 rebels were known to have spoken some English. As planned, they gained participants as they moved from plantation to plantation along the east bank of the Mississippi River. There is considerable disagreement on how well-organized the rebels were. The only eyewitness testimony says they were formed clan-like, similar to their tribal associations in Africa. The rebels attacked and burned five empty plantations; most owners were already in New Orleans at the start of the revolt.

Most owners did not "flee" to New Orleans; they crossed the river to assemble the Militia. The Fifth Militia Regiment, under Major Charles Perret, began chasing the rebels at around 9 a.m. on January 9 with only 21 men. When he discovered that the insurgents, camped on the farm of Jacques Fortier, numbered about 200, he returned to Judge St. Martin's house to report what he saw. The Militia gathered more men and planned to attack the rebels early the following day. The insurgents could cross about 25 miles before being stopped on January 10 by U. S. troops from New Orleans. Major Perret attacked the rebels with only 60 men that morning. After the initial volley, most of them surrendered.

The slave owners had fled to New Orleans, and territorial governor William C. C. Claiborne had dispatched the company to put down the rebellion. Most rebels were captured or escaped into the swamps, leaving a much smaller group of rebels to face the Militia. Deslondes was one of the first to leave the battlefield. He was caught two days later; he was tried and executed on Andry's plantation. Before the end, he and his compatriots freed about 25 miles of territory; they backtracked 15 miles and were stopped by a force of Militia three to four times smaller than the rebel "army.” The rebels left at least two slave owners killed, and three plantations burned completely to the ground.

The leaders, on horseback, made the fastest escape and fled into the swamps, chased by the Militia. The captured prisoners (numbering three times their captors) were taken to the Destrehan plantation. The "Army,” under command of General Hampton, did not arrive on the scene until January 11. ninety-five slaves were killed or tried and executed because of this revolt. Fifty-six of those slaves captured on January 10 and involved in the revolt were returned to their masters. Thirty more slaves were captured, but they had been forced to join the revolt by Charles Deslondes and his men and were also returned to their masters.

The rebels killed at least three slaves for not wanting to participate in the revolt. Following the required 40-day waiting period, seven slaves were freed after the revolt due to their actions to prevent it.

Black First:

2,000 years of extraordinary achievement

by Jessie Carney Smith

Copyright 1994 Visible Ink Press, Detroit, MI

ISBN 0-8103-9490-1