*The Baptist War began on this date in 1832. Also known as the Christmas Rebellion, it was an eleven-day rebellion that started on Christmas Day 1831 in Jamaica.

The missionary-educated rebels had been following the progress of the abolitionist movement in London; they intended to call for a peaceful general strike. The relative independence of Black deacons facilitated slaves' greater ownership over their religious life. Thomas Burchell, a missionary in Montego Bay, returned from England following Christmas vacation. Many Baptist ministries expected he would return with papers for emancipation from the King, William IV. They also thought that the King's men would enforce the order, and discontent escalated among slaves when the Jamaican governor announced that no emancipation had been granted.

Led by Black Baptist preacher Samuel Sharpe, enslaved Blacks demanded more freedom and a working wage of "half the going wage rate"; they took an oath to stay away from work until the plantation owners met their demands. The enslaved laborers believed that the work stoppage could achieve their ends alone. A resort to force was only envisaged if violence was used against them. Sharpe was the inspiration for the rebellion. His military commanders were mainly literate slaves like him.

They included Johnson, a carpenter called Campbell from the York estate, a waggoner from the Greenwich estate named Robert Gardner, Thomas Dove from the Belvedere estate, John Tharp from Hazlelymph estate, and George Taylor, who, like Sharpe, was a deacon in Burchell's chapel. It became the largest slave uprising in the British West Indies, mobilizing as many as 60,000 of Jamaica's 300,000 slaves. During the rebellion, fourteen whites were killed by armed slave battalions, and 207 rebels were killed.

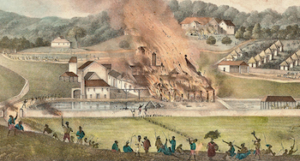

The rebellion exploded on December 27, when slaves set fire to Kensington estate in the hills above Montego Bay. Colonel William Grignon of the militia led the militia against the rebels at Belvedere estate. Still, he was forced to retreat, leaving the rebels in command of the rural areas of the parish of St James. On December 31, the colonial authorities instituted martial law. Sir Willoughby Cotton commanded the British forces and summoned the Jamaican Maroons of Accompong Town to help suppress the rebellion in the second week of January. The Accompong Maroons soon gained the upper hand, killing one of Sharpe's deputies, Campbell, in the assault.

Accompong Maroons captured scores of rebels, including another of Sharpe's deputies, Dehany. When the Windward Maroons from Charles Town, Jamaica, and Moore Town answered the call of Cotton, the rebel cause was lost. These eastern Maroons killed and captured several other rebels, including another leader named Gillespie. One of the last leaders of the insurgents, Gardner, surrendered. After the rebellion, property damage was estimated in the Jamaican Assembly summary report in March 1832 to be £1,154,589 (roughly £124,000,000 in 2021). Thousands of rebels had set fire to more than 100 properties, destroying over 40 sugar works and the houses of nearly 100 planters. The planters suspected many missionaries of having encouraged the rebellion. Groups of white colonials destroyed chapels that housed Black congregations.

Aftermath

As a result of the Baptist War, hundreds of slaves ran away into the Cockpit Country to avoid being forced back into slavery. The Maroons were only successful in apprehending a small number of these runaway slaves. Historians argue that the brutality of the Jamaican plantocracy during the revolt accelerated the British political process of emancipating the slaves. When Burchell and Knibb described how badly the colonial militias treated them, the House of Commons expressed their outrage that white planters could have tarred and feathered white missionaries.

A total of 310 to 340 were executed through the judicial process, including many for minor offenses such as theft of livestock. The Jamaican government's severe reprisals in the aftermath of the rebellion are believed to have contributed to the passage by Parliament of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act and the final abolition of slavery across the British Empire in 1838.