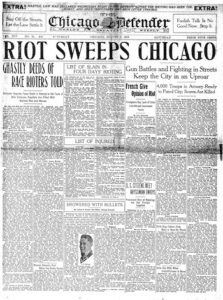

*On this date in 1919, the Chicago Race Riot occurred. This was a week-long violent American racial conflict provoked by Whites against Blacks.

It began on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, on August 3, 1919. During the riot, thirty-eight people died (23 black and 15 white). Over the week, injuries attributed to the episodic confrontations stood at 537, with two-thirds of the injured being Black and one-third white, while the approximately 1,000 to 2,000 who lost their homes were mostly Black. It is considered the worst of the nearly 25 riots in the United States during the "Red Summer" of 1919, so named because of the racial and labor-related violence and fatalities nationwide. The combination of prolonged arson, looting, and murder made it one of the worst race riots in the history of Illinois.

In early 1919, the sociopolitical atmosphere in Chicago, particularly around and near its rapidly growing black community, was marked by ethnic tension stemming from competition among new groups, an economic slump, and the social changes brought about by World War I. With the Great Migration, millions of Blacks from the American South had settled in neighborhoods adjacent to those of white immigrants on Chicago's South Side, near jobs in the stockyards, meatpacking plants, and other industries. Meanwhile, the Irish had been established earlier and fiercely defended their territory and political power against all newcomers. Post-World War I tension led to inter-community frictions, particularly in the competitive labor and housing markets. Overcrowding and increased black resistance against racism, especially by war veterans, contributed to the visible racial friction. Also, a combination of ethnic gangs and police neglect strained the racial relationships.

The turmoil boiled during a summer heatwave with the death of Eugene Williams, a black youth who inadvertently drifted into a white swimming area at an informally segregated beach near 29th Street. Tensions between groups escalated into a melee that lasted for days of unrest. Black neighbors near white regions were attacked, white gangs went into black neighborhoods, and black workers seeking to get to and from employment were attacked. Meanwhile, some blacks organized to resist and protect, and some whites sought to aid blacks, while the Chicago Police Department often turned a blind eye or worse. William Hale Thompson was the Mayor of Chicago during the riot. A game of brinksmanship with Illinois Governor Frank Lowden may have exacerbated the riot since Thompson refused to ask Lowden to send in the Illinois Army National Guard for four days, despite Lowden having ensured that the guardsmen were called up, organized in Chicago's armories, and made ready to intervene.

An interracial official city commission was convened to investigate causes and issued a report that urged an end to prejudice and discrimination. United States President Woodrow Wilson and the United States Congress sought to promote legislation and organizations aimed at reducing racial discord in America. Governor Lowden took several actions at Thompson's request to quell the riot and promote greater harmony in its aftermath. Sections of the Chicago economy were shut down for several days during and after the riots since plants were closed to avoid interaction among bickering groups. Mayor Thompson drew on his association with this riot to influence later political elections.

One of the more lasting effects may have been decisions in white and black communities to seek greater separation. The rioting impacted Chicago's economy. Low-income areas, such as tenement housing, were particularly vulnerable to potential riots. Some of the South Side's industries were closed during the riot. Businesses in the Loop were also affected by the closure of the streetcars. Many workers stayed away from the affected areas. At the Union Stock Yard, one of Chicago's largest employers, all 15,000 Black workers were initially expected to return to work on Monday, August 4, 1919. But after arson near white employees' homes near the stockyards on August 3, the management banned black employees from the stockyards in fear of further rioting.

Governor Lowden noted that the troubles were related to labor issues rather than race. Nearly one-third of the black employees were non-union and were resented by union employees for that reason. Black workers were kept out of the stockyards for ten days after the end of the riot because of continued unrest. On August 8, 1919, about 3,000 non-union Blacks showed up for work under the protection of special police, deputy sheriffs, and militia. The white union employees threatened to strike unless such security forces were discontinued. Their main grievance against blacks was that they were non-union and had been used by management as strikebreakers in earlier years. Many blacks fled the city as a result of the riots and damage.

Illinois Attorney General Edward Brundage and State's Attorney Hoyne gathered evidence to prepare for a grand jury investigation. The intention was to pursue all perpetrators and seek the death penalty as necessary. On August 4, 1919, seventeen indictments were handed down against Blacks. In 1922, six whites and six blacks were commissioned to discover the true roots of the riots. It claimed that returning soldiers from World War I were not receiving their original jobs and homes, which instigated the riots. In 1930, Mayor William Hale Thompson, a flamboyant Republican, invoked the riot in a misleading pamphlet urging African Americans to vote against the Republican nominee, Rep. Ruth Hanna McCormick, in the United States Senate race for her late husband's seat. She was the widow of Sen. Joseph Medill McCormick and the sister-in-law of Chicago Tribune publisher Robert Rutherford McCormick. The McCormicks were a powerful Chicago family whom Thompson opposed.

President Woodrow Wilson pronounced white participants the instigators of the prolonged riots in Chicago and Washington, D.C. As a result, he attempted to promote greater racial harmony by encouraging voluntary organizations and advocating for legislative improvements in Congress. However, he did not change the segregation of federal departments, which he had imposed early during his first administration. The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 shocked the nation and raised awareness of the problems that African Americans faced every day in the early 20th century in the United States.