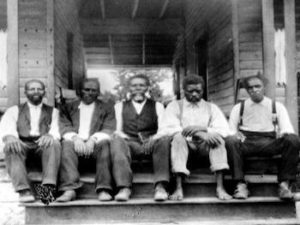

C.F.N.A.C.U. early members

*The Colored Farmers National Alliance and Cooperative Union were founded on this date in 1886. It was founded in Houston County, Texas, on the farm of R.M. Humphrey, a white Alliance member and Baptist missionary.

The alliance elected J. J. Shuffer as its first president. Although the orders' charter barred whites from membership, Humphrey was elected honorary superintendent. As increasingly repressive Black Codes were enacted, Humphrey served as a "white spokesman who could openly express militancy and have access that would be denied to Blacks." By 1888, the alliance received a charter from the Federal Government. They quickly spread and found chapters in different states across the South. In 1890, they merged with a rival alliance, the National Colored Alliance. They also absorbed the Colored Agricultural Wheels in Arkansas, western Tennessee, and Alabama. By 1890, the Colored Farmers' Alliance had over 1,200,000 members.

The order’s statement of principles was in the vein of Booker T. Washington, promoting economic self-sufficiency and racial ‘uplift’ through vocational training at the expense of demands for political equality. They tried to educate the farmers about better farming tactics and techniques. They set up exchanges in Norfolk, Charleston, Mobile, New Orleans, and Houston, where members could purchase discounted items required for their farming. They advocated for members to avoid debt through hard work and sacrifice and suggested goals such as homeownership. They collaborated with the white Farmers' Alliance in opposing the Louisiana State Lottery Company and efforts to tax the production of cottonseed oil, an extremely valuable crop for Black tenant farmers. However, the two alliances split in 1890 over a Federal Elections Bill introduced in the House of Representatives by Rep. Henry Cabot Lodge that authorized federal supervision of voter registration and voting.

It was designed to end the suppression of Southern Republican voters, particularly Black voters, whom the Democratic state legislatures had pressured. Virtually all white Southerners, including the Farmers' Alliance, denounced the bill as a return to the policies of Reconstruction, and the Democrats succeeded in making it the central issue of the 1892 Presidential election in the South.

Humphrey sought to downplay the issue, insisting that black suffrage would be protected through the Alliance movement. Most Black Populists supported renewed federal intervention to preserve their civil rights, which state changes to voter registration and electoral laws had eroded. 1891, after the election bill split, the Colored Alliance called a general strike of Black cotton pickers to demand a wage increase from 50 cents to $1 per hundred pounds of cotton.

The white Farmers' Alliance, whose membership in the South included large numbers of landowners employing sharecroppers, were the most vehement opponents of the proposed strike. The Progressive Farmer, a paper of Farmers Alliance President Leonidas L. Polk, urged “our farmers to leave their cotton in the field rather than pay more than 50 cents per hundred to have it picked.”

The leadership of the Colored Alliance lacked the resources to mobilize the vast majority of sharecroppers who were illiterate or semi-literate and lacked alternative sources of income. The Georgia chapter of the Colored Alliance, with a large contingent of landowners, refused to support the strike, viewing it as detrimental to the interests of Black farmers who owned or rented their land. A minor cotton picker strike of 1891 in the Arkansas Delta in September was crushed by local vigilantes, resulting in the death of fifteen strikers, including several who were lynched.

By the end of 1891, with the failure of the cotton pickers strike, the Colored Farmers' Alliance began to decline in membership and political influence. The Texas branch continued to be active by the spring of 1892. Alex Asberry, a Black Republican state legislator from Robertson County, was elected state president and founded the Alliance Vindicator newspaper. But, by the end of 1892, the Texas Colored Farmers' Alliance had largely disappeared. By extension, the National Colored Farmers' Alliance disappeared after 1896 with the demise of the Populist Party, from which its members were generally recruited.