*On this date in 1857, the United States Supreme Court decided the Dred Scott Case. Many believe it was a key cause of the American Civil War and the ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, leading to the end of slavery and the beginning of civil rights for freed African slaves.

The 1800s were consumed with sectional strife, primarily about race. This brought about the Dred Scott decision and irreversible impetus toward civil war. No case in American judicial history has achieved as much notoriety as Dred Scott. The case continues to symbolize the marginal status in which African Americans often have been held in the social and political order of the United States. Dred Scott was the slave of a U. S. Army surgeon, John Emerson of Missouri, a state that permitted slavery. In 1834, Scott traveled with Emerson to live in Illinois, where slavery was prohibited. They later lived in the Wisconsin territory.

In 1836, Emerson and Scott moved to Fort Snelling, an army post in Minnesota; in both of the later areas, slavery was prohibited by the Missouri Compromise. At Fort Snelling, Scott married Harriet Robinson, a slave. In 1837, Emerson left Fort Snelling for Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis. Scott and his wife stayed behind in Fort Snelling but joined Emerson in 1838. The Scotts eventually returned to St. Louis with Emerson in 1840.

In 1846, after Emerson died, Scott sued Emerson’s widow to gain freedom for himself, his wife Harriet, and their two children. Scott argued that living at Fort Snelling had made him and his family free and that once free, they remained free, even after returning to Missouri. In January 1850, a jury of 12 White men on the St. Louis Circuit Court concluded that Scott’s two years of residence in a free state and a free territory made him free. However, in 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed this decision, claiming that due to Northern hostility toward slavery, Missouri would no longer recognize federal or state laws that might have emancipated Scott.

In 1854, Scott turned to the federal courts and renewed his quest for freedom in the U. S. Circuit Court in Missouri. Scott’s owner at this time was Emerson’s brother-in-law, John F. A. Sanford argued that Blacks could never be citizens of the United States and, therefore, could never sue in federal court. Federal Judge Robert Wells ruled that if Scott was free, he was entitled to sue in federal court as a citizen. However, after a trial, Wells decided Scott was still a slave. Scott then appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court.

The court heard his case, formally known as Scott v. Sandford, in the spring of 1856 but did not decide it that year. Instead, the court ordered new arguments to be conducted in December 1856, after the presidential election. Montgomery Blair was postmaster general in the Cabinet of President Abraham Lincoln, and George T. Curtis, brother of Supreme Court Justice Benjamin R. Curtis, represented Scott for free. U. S. Senator Henry S. Geyer of Missouri and Reverdy Johnson, a Maryland politician and close friend of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, represented Scott’s owner.

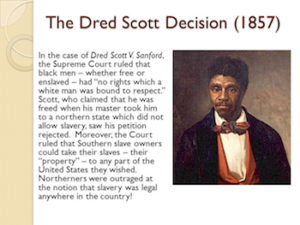

In March 1857, the court ruled in a 7 to 2 decision that Scott was still a slave and, therefore, not entitled to sue in court. For the first time in history, each of the nine justices on the court wrote an opinion in the same case, explaining their various positions on the court’s decision. Chief Justice Taney’s 54-page majority opinion of the court had wide-ranging effects. In it, he argued that free Blacks, even those who could vote in the states where they lived, could never be U. S. citizens. At the time, some or all adult Black males could vote in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, and New York, and Blacks had held public office in Ohio and Massachusetts. Nevertheless, Taney declared that even if a Black was a citizen of a state, "It does not by any means follow... that he must be a citizen of the United States." Taney based this unprecedented legal argument entirely on race.

Although he knew that some Blacks had voted at the time of the ratification of the Constitution of the United States in 1787, Taney nevertheless argued that Blacks "are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution... On the contrary, they were at that time (1787) considered a subordinate, inferior class of beings the dominant race had subjugated, and... had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and Government might choose to grant them."

In words that shocked much of the North, Taney declared Blacks were "so far inferior, that they had no rights, which the White man, was bound to respect.” Taney concluded that Blacks could never be citizens of the United States, even if they were born in the country and considered to be citizens of the states in which they lived.

Shortly after Taney's decision on May 26, 1857, Scott gained his freedom when the sons of his first owner, Peter Blow, purchased and freed him and his family. Scott remained a free man until his death a few months later, on September 17, 1858. His case, however, remained an essential issue in American politics and law until the outbreak of the Civil War.

Historic U.S. Cases 1690-1993:

An Encyclopedia New York

Copyright 1992 Garland Publishing, New York

ISBN 0-8240-4430-4