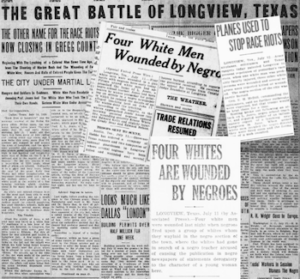

Newspapers clippings

*The Longview race riot occurred on this date in 1919. This was a weak episode of violent incidents in Longview, Texas. From July 10 to July 17, whites attacked Black areas of town, killed one Black man, and burned down several properties, including the houses of a black teacher and a doctor. It was one of the many American race riots that year during what became known as Red Summer.

Following service by many Blacks in the military in World War I, they aspired for better treatment in the United States. East Texas Blacks were in touch with national movements and media, as represented by the weekly delivery by a train of the influential The Chicago Defender, a weekly newspaper with nationwide coverage and circulation. The local reporter and newspaper distributor was Samuel L. Jones, a schoolteacher. At the time, Jones and Dr. Calvin P. Davis, a 34-year-old Black physician, were prominent leaders in Longview's Black community.

Not long before the riot, the two encouraged local Black farmers to avoid white cotton brokers and sell directly to buyers in Galveston to keep more of their profits. At the same time, members of the Negro Business League had set up a cooperative store that competed with white merchants. In June, local man Lemuel Walters of Longview had been whipped by two white men from Kilgore, allegedly for making "indecent advances" toward their sister. (One account said he was found in her bedroom.) Under Jim Crow, white men strictly monitored and discouraged relations between Black men and white women, but not the reverse. Walters was arrested and put in jail in Longview. A lynch mob of ten men abducted him on June 17 and killed him that night by gunshots, leaving him near the railroad tracks.

Dr. Davis, Jones, and some other Black men visited Judge Bramlette in town, asking him to investigate the lynching. He asked for the names of people Jones had talked to at the jail. When no investigation was undertaken, the men returned to Judge Bramlette but became convinced he did not intend to pursue the case. On July 5, 1919, The Chicago Defender published an article about Walters' death. It said that "Walters' only crime was that a white woman loved him," and it quoted her (unnamed) as saying that she "would have married him if they had lived in the North." The article described her as "so distraught over his death that she required a physician's care." It said the sheriff guarding Walters had let the lynch mob take him without offering resistance. While the article did not identify the woman, in those small towns, many readers knew who she was.

Some were offended at the suggestion that she had loved Walters, saying it damaged the young woman's reputation. As Jones was known to be a local correspondent for the Defender, whites believed he wrote the article. He denied having written it. The young woman's brothers attacked Jones on July 10, 1919, beating him across from the courthouse. Davis arrived in his car soon after and took Jones to his office to treat him. Meanwhile, "tension and anger" spread across town as whites learned of the article and Blacks gathered at Melvin Street and learned about the beating.

Marion Bush was a 60-year-old Black man who had worked with the local Kelly Plow Company and was Dr. Davis's father-in-law. On the night of July 12, Sheriff Meredith and Ike Killingsworth went to Bush's house, offering Bush protective custody or intending to arrest him. Alarmed, Bush fled from the house after reportedly firing shots at the sheriff. There are differing accounts as to what happened next. From interviews in 1978 and a contemporary Dallas newspaper, Durham says the sheriff called farmer Jim Stephens and asked him to stop Bush. He found and ordered him to stop, but Bush ran into a cornfield. Stephens followed, shooting and killing him. According to the same Dallas Morning News of July 13 and 14, "armed white citizens" hunted down Bush, killing the 60-year-old man in a cornfield south of town.

Local officials feared a new wave of civil unrest when they heard of Bush's killing. They called Governor Hobby again for aid, and he sent about 160 more soldiers and Texas Rangers. On Sunday, July 13, Hobby declared martial law in all of Gregg County, placing Brigadier General Robert H. McDill in command of the soldiers and the rangers. General McDill issued orders, dividing the town into two districts, giving command of one section to Colonel T.E. Barton and the other to Colonel H.W. Peck. The riot ended after local and state officials took action to impose military authority and quell further violence. After ignoring early rumors of planned unrest, local officials appealed to the governor for forces to quell the violence. In a short time, the Texas National Guard and Texas Rangers sent forces to the town, where the Guard organized an occupation and curfew.

No one was prosecuted for the events, although the Rangers learned the identity of the "ringleader" of the riot, who gave them names of sixteen other men involved in the first attack on Jones' house. All were arrested for attempted murder on July 14 but quickly released. The Rangers learned the names of nine other suspects, arresting them for arson; they were also released on bonds. Captain Hanson also questioned black residents, ultimately arresting twenty-one Black men for assault and attempted murder. He temporarily placed them in the county jail, removing them to Austin for safety.

An organized an assembly at the courthouse and informed the public of the arrests, the presence of National Guard troops and Texas Rangers, and expectations. Brigadier General Jake F. Wolters also spoke to the citizens. The twenty-one blacks were taken to Austin by the Texas National Guard. The prisoners were separated into smaller groups and placed in various county jails, at Gregg County's expense, until they could be tried in a Gregg County court. The blacks who had helped defend their home were told not to return to Longview, but others returned to relative peace. The governor lifted martial law at noon on July 18. Residents were allowed to begin picking up their guns the next day. Town officials tried to promote "harmonious relations" between the races. No one was ever tried. Durham suggests that Gregg County officials chose to avoid trials to defuse the tension, perhaps believing that at trial by the all-white juries of this period, the whites were likely to be acquitted and the blacks convicted. No documentation relates to the decisions about not pursuing prosecution.

Aftermath:

Dr. Davis and Samuel Jones reached Chicago after fleeing Longview and eventually settled there with their families. By that date, racial conflicts had erupted in numerous large and small cities across the country, including Chicago, which had a week of violence ending in early August that resulted in 38 deaths and more than 500 people injured as extensive property damage. The violence of whites against blacks continued into the fall, with a riot in Omaha, Nebraska, in late September; Blacks continued to defend themselves into the 21st century.